The Financial Institutions Group (FIG): Specialization Superhighway or Dreary Dungeon?

Depending on the person, the Financial Institutions Group (FIG) could be the most technically challenging and interesting group to work in or a bottomless dungeon with lava-dwelling crocodiles that eat children all day.

These views differ dramatically because the merits of the group depend on your goals going into investment banking.

If your lifelong ambition is to work at KKR or Blackstone doing leveraged buyouts of industrial or retail companies, no, FIG investment banking is not the place to be.

But if you’re interested in the most different sector in IB, you want constant deal flow, and you want to advise banks, insurance firms, and other financial companies, nothing beats FIG.

- FIG Investment Banking: All About the Financial Institutions Group

- Recruiting: Who Gets Into the Financial Institutions Group?

- What Do You Do as an Analyst or Associate in FIG Investment Banking?

- Financial Institutions Group Trends and Drivers

- Financial Institution Group Overview by Vertical

- Accounting, Valuation, and Financial Modeling in the Financial Institutions Group

- Example Valuations, Pitch Books, Fairness Opinions, and Investor Presentations

- FIG Investment Banking League Tables: The Top Firms

- Exit Opportunities from the Financial Institutions Group

- Pros and Cons of the Financial Institutions Group (FIG)

- Want More?

Let’s start with the key definitions, setting, and dramatis personae:

FIG Investment Banking: All About the Financial Institutions Group

Financial Institutions Group Definition: In FIG investment banking, professionals advise commercial banks, insurance companies, specialty finance firms, brokerage/exchange companies, asset management firms, and financial technology companies on raising debt and equity and completing mergers and acquisitions.

Yes, that’s a mouthful.

Historically, the financials sector has generated the highest fees for large investment banks, so they devote many resources to it.

That is primarily because the debt issuance volume is 10-20x that of other industries (for reasons we’ll explain below), which creates a lucrative fee pool.

All the verticals within FIG relate to turning other peoples’ money into more money without pesky physical products in between.

But the details are quite different, so here’s a quick overview:

- Commercial Banks: Banks issue loans to companies and individuals, charge interest on these loans, and collect deposits from consumers and issue debt to back the loans (Loans are assets; deposits and debt are liabilities). Banks make money via the spread between the interest income earned on loans and the interest expense paid on deposits and debt.

- Insurance: These firms transfer risk. Customers pay premiums so that in the case of an expensive disaster (a hurricane destroying a home, a car crash, someone dying, etc.), they are compensated by the insurance firm. Due to the timing mismatch between collected premiums and losses (payouts to customers), these firms use the money to invest and earn interest, dividends, and capital gains in addition to the income from writing premiums.

- Specialty Finance: These companies provide “alternative lending” models: credit card and other consumer finance companies, mortgage banks, commercial finance, leasing, mortgage REITs, asset-backed lending, and so on. They have similar drivers to commercial banks, and the same accounting and valuation principles apply as well.

- Brokerages, Exchanges, and Investment Banks: They facilitate transactions and earn commissions on trades, whether the trades are tiny or multi-billion-dollar deals. These firms are highly dependent on market activity, whether it’s traditional equities and fixed income, huge M&A deals, or cryptocurrencies.

- Asset Management Firms: They collect money from investors who need someone to manage it, and they charge a fee for their investment management services. There may also be other income sources, such as administrative and servicing fees.

- Financial Technology (FinTech): These companies support the other financial players with software, services, and automation tools. Think: payment and transaction processing, card networks, and financial software. Common business models include commissions and recurring subscription fees.

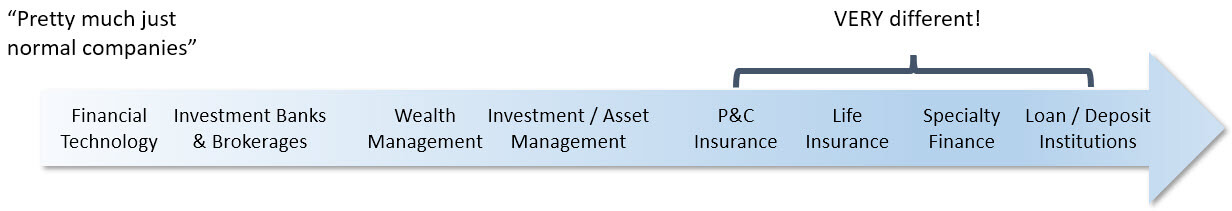

Of these verticals, the first three – commercial banks, insurance, and specialty finance – are the most different in terms of accounting, valuation, and financial modeling:

People often assume that “everything” in FIG is different, but that is not true.

For example, you could easily use a DCF model and standard multiples like TEV / EBITDA to value a broker-dealer, an asset management firm, or a FinTech company.

But you could not use them for a commercial bank or a life insurance firm.

Recruiting: Who Gets Into the Financial Institutions Group?

The same types of candidates who get into investment banking anywhere also get into FIG investment banking: your university or business school, internships, grades, networking, and recruiting/interview prep matter most.

Although certain sectors within FIG use very different accounting and valuation, bankers don’t necessarily expect you to know all the details going into it as an Analyst.

It helps to know the basics, such as what’s covered in this article and our Bank Modeling tutorial, but you don’t need to be an expert; you’ll still get standard technical questions as well.

Similarly, FIG-specific experience helps, but it’s more important at the MBA and lateral hiring levels, as bankers want industry specialists there.

Compared with other specialized industry groups, there are fewer opportunities to break in through “the side door.”

With real estate investment banking, for example, you could gain experience in dozens of real estate-related roles (e.g., CRE brokerage, property management, real estate lending, etc.) and use it to move into an investment or advisory role.

But these adjacent roles are less common in the financial institutions space, so if you want to be in this group, you should start early and stay specialized.

What Do You Do as an Analyst or Associate in FIG Investment Banking?

This one depends heavily on your vertical and the size of your firm.

If you advise large commercial banks, expect many debt deals and relatively few M&A mega-deals.

There is plenty of M&A activity within commercial banking, but due to regulations on the percentage of total deposits in a country that may be held by one bank following an acquisition, it’s concentrated among smaller firms.

Larger banks may be more active in smaller acquisitions, especially of non-depository firms, and in divestitures and spin-offs.

Equity issuances happen as well, but mostly when banks need to shore up their “regulatory capital” (see below).

Deal activity is more varied in insurance, but you’ll still see more debt deals and fewer equity and M&A deals.

In the other FIG verticals, deal flow will be even more varied, but you’ll see more equity and M&A deals in FinTech because it’s the “high-growth” area.

Finally, traditional leveraged buyouts are not common in any of these verticals.

That’s because of regulatory issues and the inability to “lever up” these firms, as they’re already highly leveraged and constantly issue debt.

That said, private equity has become increasingly active in insurance over time, and LBOs in the sectors such as FinTech are possible for more mature companies.

Financial Institutions Group Trends and Drivers

Most financial institutions – except FinTech – have the following qualities in common:

- They tend to follow the broader markets but with “cycles” that don’t necessarily correspond to broader economic cycles.

- Companies tend to be value-oriented because many firms in the sector issue stable, predictable dividends and trade at somewhat lower multiples.

- They’re highly sensitive to interest rates and broader monetary policy.

- They’re heavily regulated, especially in commercial banking and insurance, where government officials set the rules and financial ratios that firms need to follow.

- They’re highly leveraged because these firms all use “other peoples’ money” to make money.

Each driver makes a slightly different impact depending on the vertical.

For example, consider interest rates: do higher rates help or harm financial institutions?

Higher rates mean that banks earn more on their loans and pay more on their deposits and debt – but they generally still come out ahead because the spread tends to increase when rates are higher.

However, higher interest rates also mean lower asset values, which could hurt bank valuation even if it helps their operational performance.

The point is that FIG is a complex sector that’s sensitive to many factors, but it’s more complicated than saying that Factor X is “good” or “bad.”

Financial Institution Group Overview by Vertical

We’ll continue with the categories above:

Commercial Banks

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Bank of Japan, ICBC (China), China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, JP Morgan, Mitsubishi UFJ (Japan), BNP Paribas, HSBC, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Crédit Agricole, and Citi.

“Commercial banks” include firms that focus exclusively on loans and deposits as well as huge, diversified companies that do a bit of everything, such as JP Morgan.

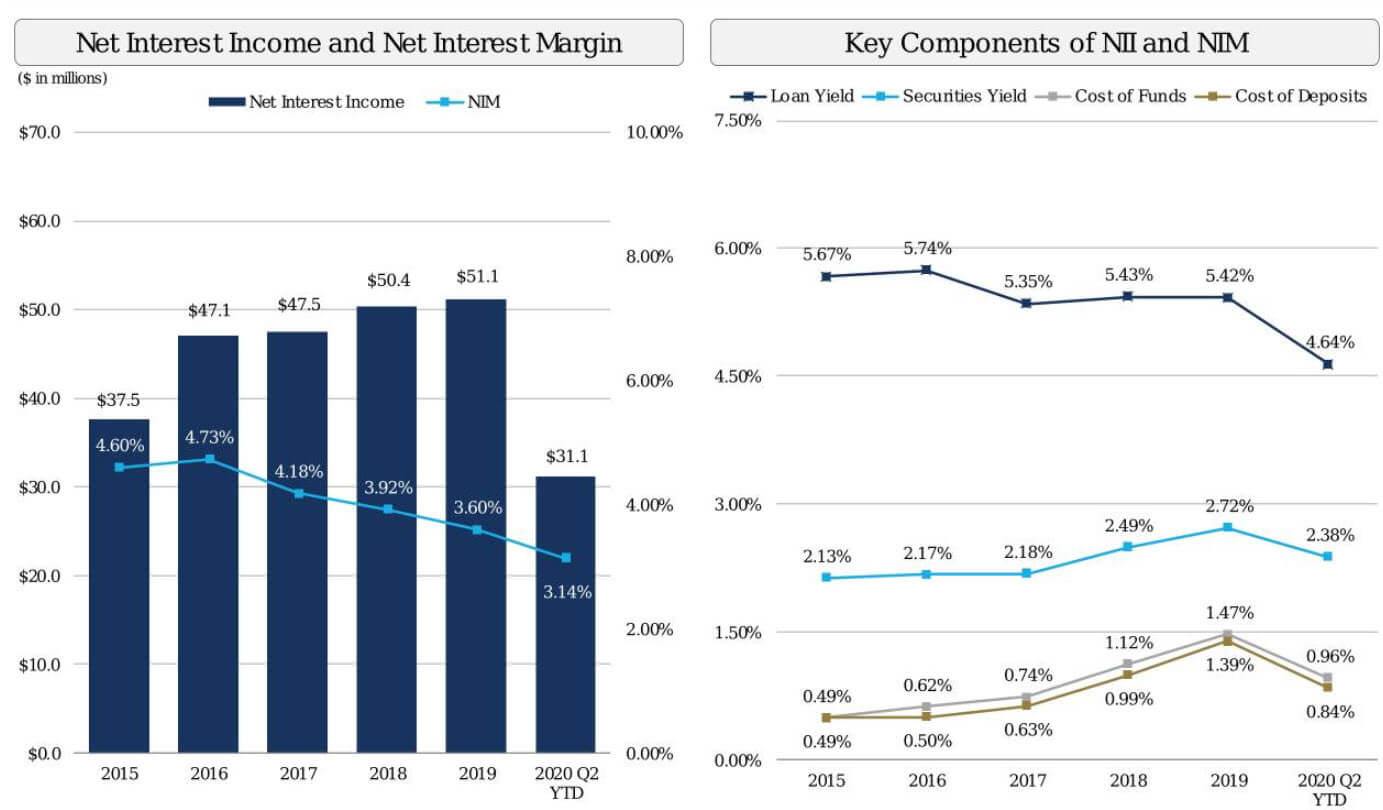

Pure-play commercial banks earn money from net interest income (interest income earned on assets minus interest expense paid on liabilities) and non-interest income (e.g., fees charged on customer deposits); the “net interest margin” is one of their key drivers:

Banks are highly sensitive to GDP growth, employment trends, business spending, and credit demand, and loan growth correlates closely with GDP growth.

Based on that, you might think that banks are similar to normal companies but with slightly different operational drivers.

Unfortunately, that’s not the case (though the drivers are indeed different).

Things get more complicated because of regulatory capital, the lack of Enterprise Value, and Dividends in place of Free Cash Flow.

When a bank issues loans, it expects that a certain percentage of borrowers will default.

It sets aside an “Allowance for Loan Losses” as a contra-Asset against Gross Loans on the Balance Sheet to account for these expected losses (over the lifespan of each loan under the CECL rules).

The bank might then adjust this Allowance over time as its expectations change.

However, the bank also has to deal with unexpected losses, which explains why “regulatory capital” exists.

If a bank experiences unexpected losses, its Net Loans decrease because it increases its “Provision for Credit Losses” on the Income Statement, which flows into the Allowance on the Balance Sheet.

This increased Provision also reduces the bank’s Net Income, which means its Common Shareholders’ Equity (CSE) decreases.

But if the bank’s CSE decreases too much, it will no longer be available to absorb losses, and depositors and debt investors will start taking losses instead – which is bad.

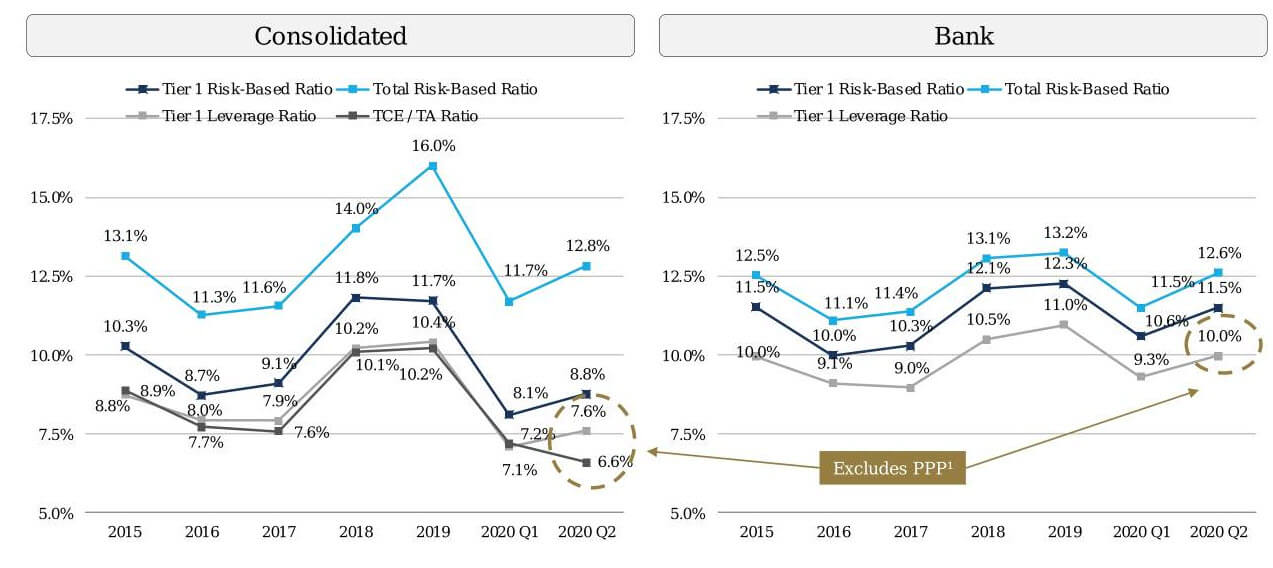

As a result, banks must maintain a certain amount of Common Shareholders’ Equity – with adjustments – relative to their “Risk-Weighted Assets.”

So, in a financial model, you cannot just assume that a bank grows its loans at 10% per year or that the average interest earned on its assets increases by 2% over time.

Instead, you need to ask questions like:

- What is the bank’s Common Equity Tier 1 (CET 1) Ratio, and is it sufficient to support this loan growth? Does the bank need to issue more equity?

- Can the bank attract enough deposits and issue enough debt to support these loans? This is why banks do so many debt deals.

- If the average interest increases by 2%, the bank is taking on more risk. How do its Risk-Weighted Assets change, and how does that affect its CET 1 Ratio and others?

In addition to this regulatory capital, the concept of Enterprise Value vs. Equity Value does not apply to commercial banks because you can’t separate operational assets and liabilities from non-operational ones.

Securities, investments, and debt are non-operational for normal companies, but they’re more like raw materials for banks.

So, you rely on Equity Value-based multiples such as P / E, P / BV, and P / TBV, as well as Equity Value-based metrics such as ROA and ROE.

Finally, “Free Cash Flow” is not a useful metric for banks because CapEx and the Change in Working Capital do not represent reinvestment in the same way they do for normal, product-based companies.

Almost everything on a bank’s Cash Flow Statement – and parts of its Income Statement such as employee compensation – could be considered “reinvestment in the business.”

So, the standard approach is to use Dividends as a proxy for Free Cash Flow and use the Dividend Discount Model rather than the traditional DCF.

Insurance

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Ping An Insurance (China), AXA (France), Allianz (Germany), China Life Insurance, Japan Post Insurance, The People’s Insurance Company of China, Assicurazioni Generali (Italy), Munich Reinsurance Company, Prudential, Legal & General Group (U.K.), MetLife, and Berkshire Hathaway.

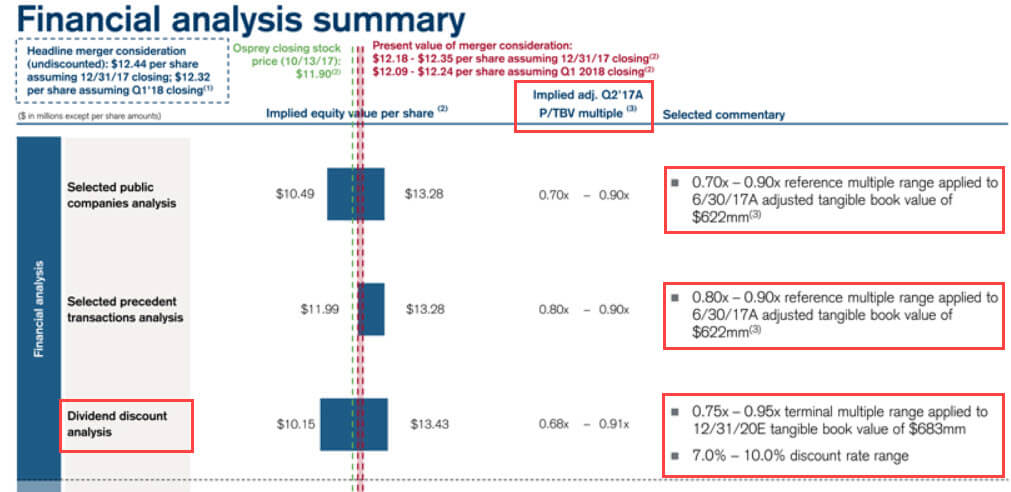

Most of the differences above for commercial banks also apply to insurance firms: you don’t use Enterprise Value or TEV-based multiples, regulatory capital is critical, and you use the Dividend Discount Model rather than a traditional DCF.

However, the specifics and drivers are different.

Insurance is more of a “flow” business, while banks are more of a “spread” business.

The two main groups here are Property & Casualty (P&C) and Life & Health (L&H), often shortened to “Life,” and they’re different mostly because of timing.

P&C firms insure items like cars and homes, which means there might be several years in between collecting premiums from a customer and paying that customer if their property gets burned down by a dragon or an army of ogres.

In the meantime, they take the premiums they collected (“the float”) and use them to invest, which is how Berkshire Hathaway became a financial giant.

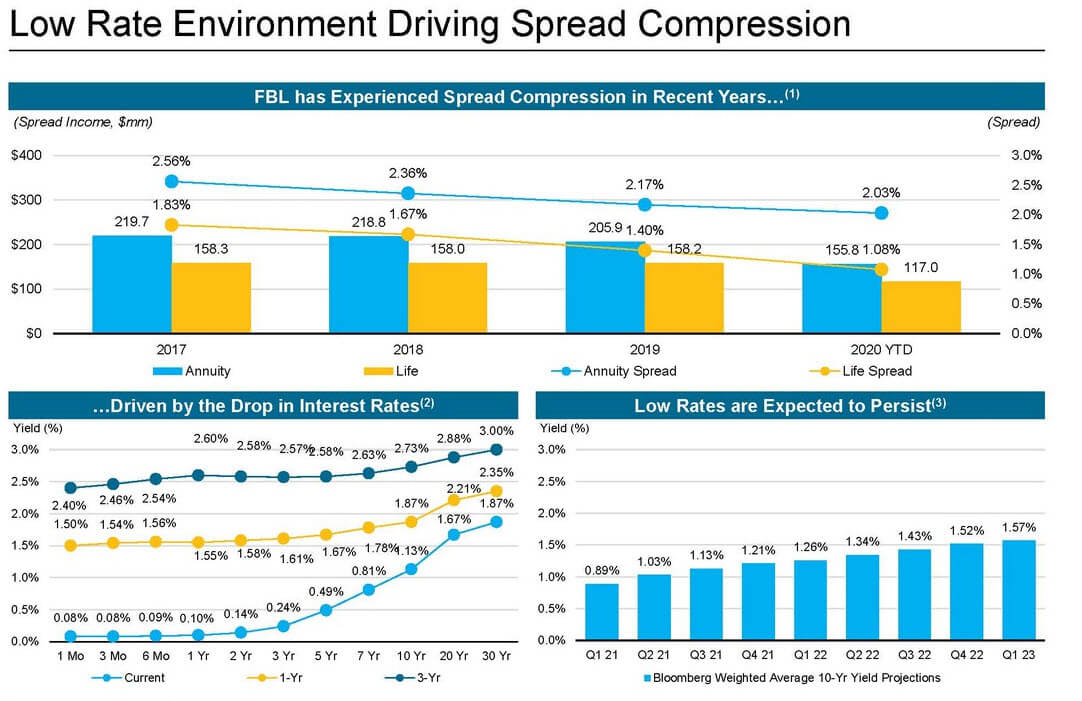

With life insurance, the timing discrepancy between premium collection and loss payout could be decades rather than years.

As a result, life insurance firms are closer to commercial banks because they’re very dependent on their investment portfolios, spreads, and dividends, interest income, and capital gains:

Insurance firms are cyclical, but since many insurance policies are required by law, they’re linked to the underwriting cycle rather than the economic one.

Initially, many firms enter the industry, driving down premiums, margins, and underwriting quality, and then a catastrophic event like a hurricane will come along and wipe out some of these firms – resulting in less competition and higher rates.

Other companies will then see an opportunity to gain market share by charging lower rates, and the cycle will repeat.

Since much of P&C insurance is auto insurance, trends in that market also hugely impact these companies: How are new and used car sales? Are prices trending up or down? Are consumers switching to bigger or smaller cars?

Life insurance is longer term, so it’s more sensitive to interest rates than P&C insurance, and it’s also affected by factors like saving trends, demographic changes, and asset values.

Regulatory capital still exists for insurance firms, but the terminology and calculations are different.

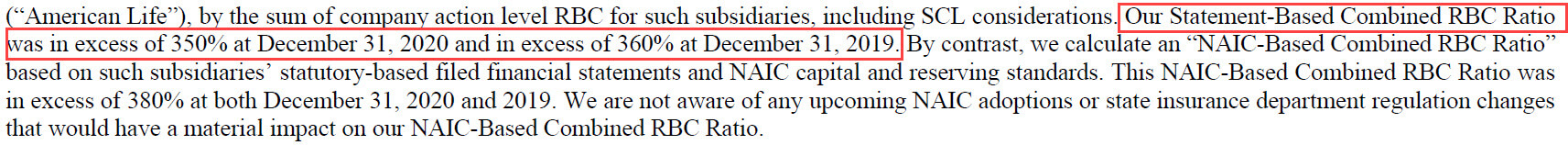

The most common metric is the “Risk-Based Capital Ratio” (RBC), which equals the insurer’s “Total Adjusted Capital” (a variant of Common Shareholders’ Equity) divided by the risk-adjusted Total Assets.

The minimum RBC Ratio varies based on the country and company, but many large insurers in the U.S., such as MetLife, often maintain ratios between 300% and 400%:

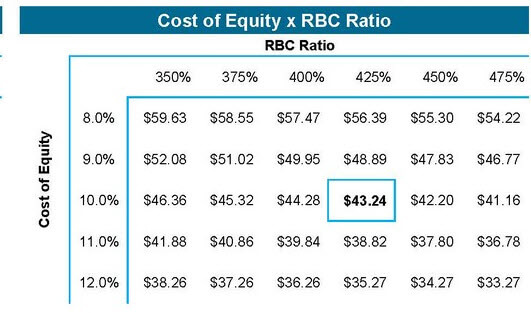

This RBC Ratio acts as a key constraint in valuation and financial modeling for insurance firms, and it often shows up in sensitivity tables for Dividend Discount Models:

Specialty Finance

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: American Express, Capital One, Discover, Mitsubishi HC Capital, Tokyo Century, Lufax (China), Synchrony Financial, Ally Financial, Fuyo General Lease, Santander Consumer, Mizuho Leasing, Far East Horizon, Annaly Capital (mortgage REIT), AEON Financial, OneMain, and New Residential Investment (mortgage REIT).

Specialty finance firms act as alternative lenders outside the traditional banking system.

That means “credit for almost anything,” ranging from auto loans to credit cards to payday loans to mortgages to agriculture to power facilities to equipment/aircraft leasing.

Many business development companies (BDCs) also fall into this category.

Mortgage REITs, which are quite different from equity REITs but still subject to the same legal requirements, are also in this category.

All the companies in this sector operate similarly to commercial banks and earn money based on the spread between the average interest rate earned on assets and the average interest rate paid on liabilities.

They don’t necessarily offer anything that the large banks do not, but they operate in markets that are too small or too “off-topic” for the large banks to pursue.

Compared with banks, the regulatory capital requirements may differ, but these firms still manage their total capital / risk-adjusted assets in some way.

And the key metrics, multiples, and valuation methodologies are nearly the same:

Brokerages, Exchanges, and Investment Banks

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Charles Schwab, S&P Global, CME Group, Intercontinental Exchange, Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing, Coinbase (???), Moody’s, MSCI, London Stock Exchange, CITIC (China), and Nasdaq.

If you’re reading this site, I assume that you know what investment banks do (read the link if not).

All the companies in this category make money with commissions charged on transactions, whether small (shares of GameStop) or large ($50 billion M&A deals).

So, they’re very close to “normal companies,” but their transaction volumes are closely linked to the capital markets, which means they’re correlated with overall fiscal and monetary conditions, including interest rates.

Higher interest rates tend to hurt these companies because people are less likely to chase returns trading meme stocks or crypto; higher rates also mean that M&A deals and debt issuances are less appealing numerically.

Some of these firms also offer fee-based services to get more stable revenue and avoid complete dependency on the capital markets.

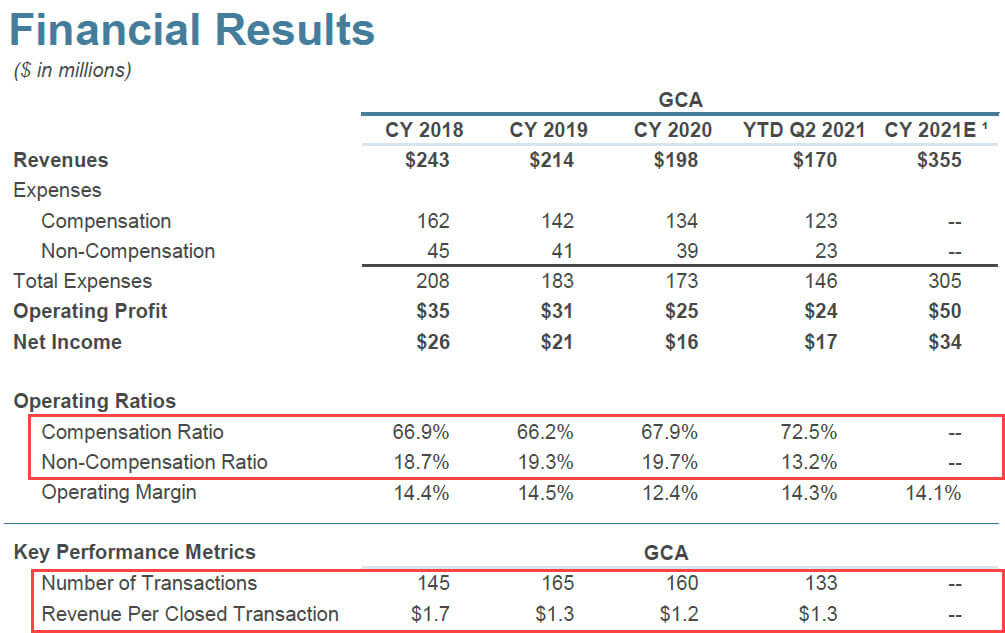

The accounting and valuation here are quite standard, but the operational metrics differ, as in the example Houlihan Lokey / GCA presentation below:

Asset Management (and Custody Banks)

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: BlackRock, Bank of NY Mellon, State Street, Ameriprise Financial, Northern Trust, Julius Bär Gruppe (Switzerland), IGM Financial (Canada), China Cinda Asset Management, Blue Owl Capital, Amundi (Italy), Vontobel (Switzerland), and Franklin Resources.

This category also includes custody banks, which simply hold financial assets rather than managing or investing them, but we’re going to focus on the “management side.”

AM firms hold and allocate their clients’ money, so revenue is driven by assets under management (AUM) and the average fee percentage.

Some firms can charge higher fees than others, and some strategies also tend to command higher fees (e.g., equity funds often charge more than fixed income ones).

Beyond investment performance, AUM, and fees, another key metric for AM firms is net flows, or new sales minus redemptions plus net exchanges.

Net flows tell you if the firm is attracting new business organically or if its AUM is growing mostly due to investment performance.

Due to pressure from automated investing platforms and passive index funds with much lower fees, the entire asset management industry has been consolidating.

That said, it will probably exist in some form forever because these firms have trillions of dollars worth of capital.

AM firms are very standard in terms of accounting, valuation, and financial modeling, and you can use normal multiples like TEV / Revenue and TEV / EBITDA to value them, along with the DCF.

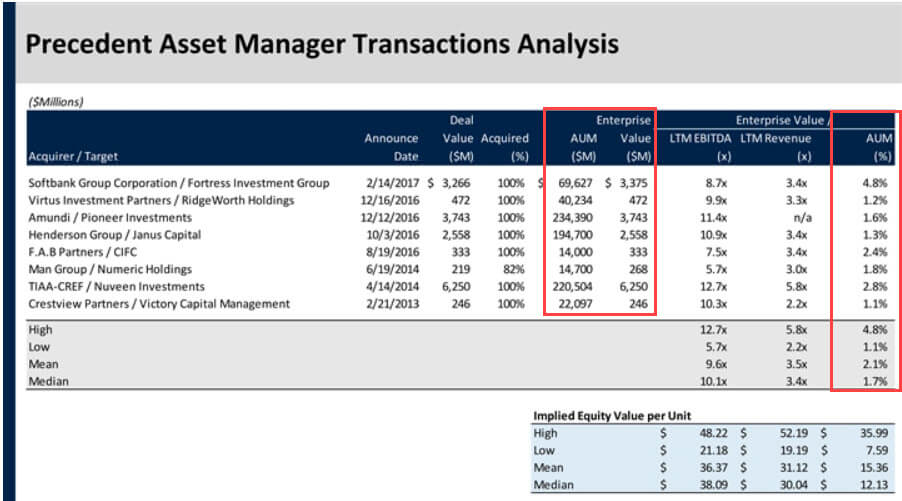

But you could potentially use the Dividend Discount Model for dividend-paying firms, and you will sometimes see the TEV / AUM multiple:

Financial Technology (“FinTech”)

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Visa and MasterCard, Square, PayPal, TenCent (FinTech business), Adyen, Fiserv, Equifax, Broadridge, FactSet, Global Payments, MercadoLibre (Mercado Pago), and Upstart.

FinTech is the least similar to everything else on this list, and it arguably shouldn’t even be in the “Financial Institutions Group” – but many banks put it there anyway.

FinTech companies are much closer to technology companies than they are to banks or insurance firms; it’s just that their customers happen to be financial institutions.

If you put “neobanks” like Revolut, N26, and Tinkoff (Russia) in this FinTech list, or you include peer-to-peer (P2P) lending companies like LendingClub or consumer finance companies like SoFi, all of those behave more like banks or specialty finance companies.

However, I would argue that business models and customers define a company, not whether it’s “new” or “old,” so we’re not counting them here.

The trends and drivers here are similar to those for banks and brokerage firms, with transaction volume and fees driving everything (and bonus subscription revenue if possible).

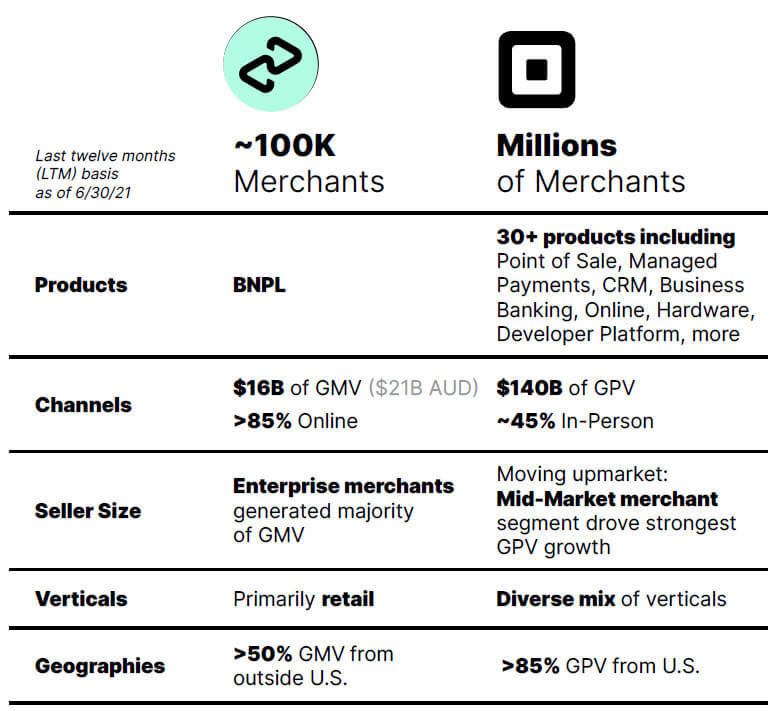

M&A deals in this sector are often motivated by expansion into new verticals and geographies and additional merchants and consumers, as in the Square / Afterpay deal:

Accounting, Valuation, and Financial Modeling in the Financial Institutions Group

We covered many of the key points earlier in this article, but in short: the technical side is very, very different for commercial banks, insurance firms, and specialty finance firms but not that different for the others.

The technical side is so different that we have an entire course dedicated to Bank & Financial Institution Modeling:

Bank Modeling

Master bank accounting, valuation, M&A, and buyouts with 4 global case studies based on Shawbrook, KeyCorp / First Niagara, ANZ, and the Philippine Bank of Communications.

learn moreI would summarize the key differences as follows:

- Accounting: For commercial banks, you need to know loan loss accounting and how the Allowance for Loan Losses is set up, how the Provision for Credit Losses affects it, and how charge-offs and reversals flow through the statements.

For insurance companies, the timing makes the accounting tricky because even if a company writes premiums for a policy and collects the cash, it can’t recognize them as revenue upfront. Instead, a line item similar to Deferred Revenue called the “Unearned Premium Reserve” is created and reduced over time, and there are similar timing issues with commissions and the reserves held for loss payouts.

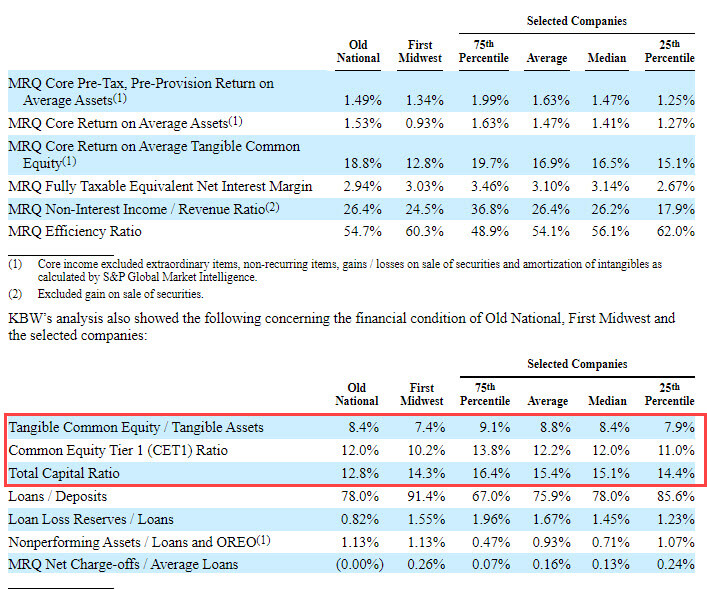

- Regulatory Capital: There are many important ratios related to the Balance Sheet for both types of firms, such as the CET 1 Ratio for banks and the RBC Ratio for insurance (and plenty of others for banks, such as the liquidity coverage ratio, net stable funding ratio, Tier 1 Capital Ratio, Total Capital Ratio, etc.):

So, you need to account for all these ratios in models and limit activities such as new premiums written, loan growth, dividend payments, and share repurchases based on the targeted vs. actual levels of regulatory capital.

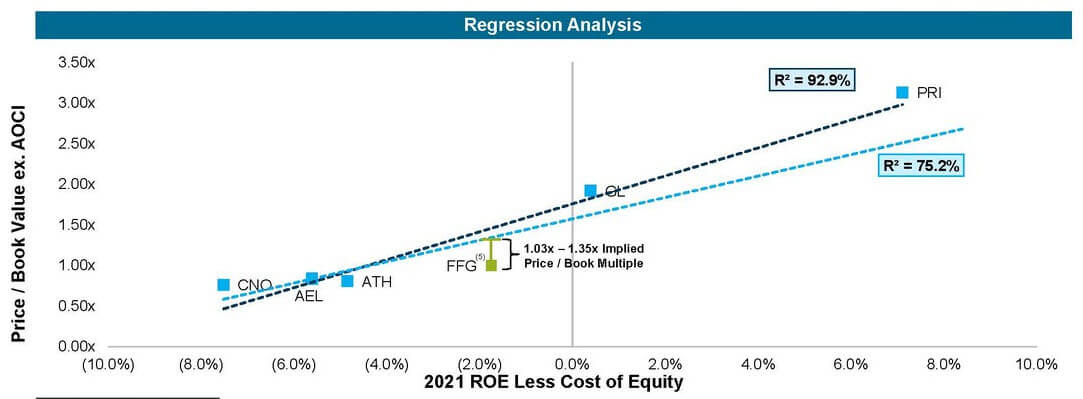

- Valuation: You use only Equity Value and Equity Value-based multiples such as P / E, P / BV, and P / TBV, along with the Dividend Discount Model. You could also use the Embedded Value model for life insurance firms, but that is a bit “academic” and less common in real life than the DDM (maybe more common outside the U.S.?). Regressions involving P / BV and ROE (and variations like P / TBV and ROTCE) are also common because of the high correlation:

- Metrics and Ratios: You focus on Equity Value-based metrics like ROA and ROE and the Dividend Payout Ratio; other important ones include the Net Charge-Off Ratio, Reserve Ratio, Net Interest Margin, and Overhead Ratio for banks and the Loss & LAE Ratio, Combined Ratio, and Solvency Ratio for insurance firms.

- M&A / LBO Modeling: Most M&A deals use 100% Stock, or at least >= 50% Stock, because these firms tend to have low Cash balances and are already highly leveraged. For banks, there are various new items in M&A deals, such as “Core Deposit Intangibles” and possible deposit divestitures; you’ll also evaluate deals using alternative methods, such as Accretion/Dilution of BV or TBV per Share and the IRR and Contribution Analysis.

Traditional leveraged buyouts are extremely rare, so most PE investing in the sector takes the shape of investing in minority stakes.

Traditional buyouts and majority-stake deals are more feasible in insurance, but they’re still not common vs. other industries.

Example Valuations, Pitch Books, Fairness Opinions, and Investor Presentations

Here are some many examples for the main verticals within FIG:

Commercial Banks

Webster Financial / Sterling Bancorp – Citi; Keefe, Bruyette & Woods (KBW); Stifel; JP Morgan; and Piper Sandler

Enterprise Financial Services Corp – $50 Million Debt Offering – Piper Sandler and U.S. Bancorp

Level One Bancorp – $25 Million Preferred Stock Offering – Piper Sandler

Old National Bancorp / First Midwest Bancorp – JPM and KBW

Insurance

Arch Capital Group / Watford Holdings (Reinsurance) – Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs

- Deal Update Presentation and Valuation (MS)

- Deal Update Presentation and Valuation – Part 2 (MS)

- Fairness Opinion – Morgan Stanley

Farm Bureau Property & Casualty Insurance Company / FBL Financial (40% “Squeeze-Out” Transaction) – Goldman Sachs and Barclays

- Investor Presentation on the Deal

- Deal / Process Update Presentation – GS

- Deal / Process Update Presentation – Barclays

Stone Point Capital / Amtrust Financial Services (Take-Private for Remaining 57% Stake) – Deutsche Bank and Bank of America Merrill Lynch

- Deal / Process Update Presentation – DB

- Investor Presentation on the Deal

- Fairness Opinion – DB

- Fairness Opinion – BAML

Specialty Finance

First Eagle Investment Management / NewStar Financial Portfolio via 2-Step Asset Purchase and Merger – Credit Suisse, Houlihan Lokey, Lincoln International, and Wells Fargo

Apollo Commercial Real Estate Finance / Apollo Residential Mortgage (Mortgage REIT) – Morgan Stanley

Marubeni and Mizuho Leasing / Aircastle (Aircraft Leasing) – Citi and JP Morgan

- Aircastle Investor Presentation with Some References to the Deal

- Deal / Process Update Presentation – Citi

- Fairness Opinion – Citi

Brokerages, Exchanges, and Investment Banks

Charles Schwab / TD Ameritrade – Credit Suisse, JP Morgan, TD, PJT Partners, and Sandler O’Neill

Houlihan Lokey / GCA Advisors – Mitsubishi UFJ, Daiwa Securities, and Plutus Consulting

Citizens Financial Group / JMP – KBW and JMP

Asset Management

Macquarie Asset Management and LPL Financial / Waddell & Reed Financial, Inc. – Macquarie, RBC, JP Morgan, and Wells Fargo

T. Rowe Price / Oak Hill – JP Morgan and Evercore

Financial Technology

Square / Afterpay – Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Qatalyst, Highbury, and Lonergan Edwards & Associates

Broadridge Financial Solutions / Itiviti – Houlihan Lokey, JP Morgan, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, and PricewaterhouseCoopers

Forge – Fundraising/Investor Presentation

FIG Investment Banking League Tables: The Top Firms

The top firms here are a bit nebulous because the ranking depends on how deals are classified (e.g., FIG vs. “financial services” vs. “financial sponsors” or “tech” vs. “fintech”).

However, if you limit the rankings to M&A advisory for financial institutions, GS, MS, and JPM tend to rank at or near the top, and other bulge bracket banks such as Citi, CS, and BAML are on the list as well.

If you expand the deals to include debt and equity issuances in addition to M&A, the firms with large Balance Sheets (e.g., JPM, Citi, CS, Wells Fargo, DB, and BAML) tend to do well.

Outside of the BB banks, the elite boutiques sometimes advise on large deals, but they’re less prominent than in sectors like Technology and TMT.

You’ll see firms like PJT Partners, Evercore, Moelis, and Lazard on the M&A advisory lists, and Qatalyst appears if you also include FinTech.

Outside these groups, it’s worth noting Piper Sandler (the merged entity of Piper Jaffray and FIG specialist Sandler O’Neill) and Stifel because of its acquisition of FIG specialist KBW.

These two firms have decades of experience and often “punch above their weight class” on deals in the sector.

The usual, strong middle market banks (e.g., Jefferies and Houlihan Lokey) do a decent amount of FIG advisory as well.

Finally, a few examples of industry-specific boutique banks include FT Partners in FinTech and Broadhaven (a merchant bank).

Exit Opportunities from the Financial Institutions Group

And now to the major downside: yes, exit opportunities from the Financial Institutions Group are more limited because you won’t be a strong candidate for most generalist roles.

If you work with commercial banks, insurance firms, or specialty finance firms, your skill set will be quite niche because you don’t model companies based on constraints around capital, liquidity, and funding stability anywhere else.

But even if you work with brokerages, asset management firms, or FinTech companies, recruiters will rarely take the time to understand your background and deal experience.

They want to spend the least amount of time possible on you, so their thought process tends to be: “They worked in FIG. OK, they can only work at FIG-focused PE firms and hedge funds. It’s specialized.”

You can sometimes get around this issue if you’ve worked in FIG at one of the top banks, but even there, you might have to trade down if you want a non-FIG buy-side role.

If you want to stay in FIG rather than become a generalist, there are exit opportunities in corporate development at many financial firms, and there are even private equity firms that focus on the sector.

Well-known names include JC Flowers, Lightyear Capital, and Stone Point Capital; others include Aquiline, Corsair, Flexpoint, and Lovell Minnick.

Some diversified firms, such as GTCR, also have FIG specialties, and larger firms like Warburg Pincus, Oak Tree, and Oak Hill Capital also operate in the sector.

All that said, there still aren’t that many PE firms that specialize in financial institutions, which means you won’t have that many firms to target for buy-side roles.

In short: yes, you can get into private equity, hedge funds, or even corporate development coming from FIG investment banking.

But if you want to be a generalist in one of those, you should move into an industry group like healthcare, technology, or industrials as soon as possible.

For Further Reading

If you’ve reached the end of this 5,000-word article and still want even more, here are some news sources and recommended resources:

- News: American Banker | Banking Dive | Insurance Journal | The Insurer | FinTech Weekly | The FinTech Times

- Books: The Valuation of Financial Companies (the only useful written reference I’ve ever found for FIG investment banking)

Pros and Cons of the Financial Institutions Group (FIG)

FIG investment banking has a lot going for it: the most deal activity of any group, quite a lot of variety in deals, companies, and business models, and a higher bar for technical skills than most other groups.

You’ll always be busy because even if there are no equity or M&A deals, banks still issue debt all the time to fund their loan growth.

If you’re a senior coverage banker, this setup can be quite lucrative because you’ll get clients that come back to your firm over and over for capital raises – and you just have to execute.

The main downside is that FIG investment banking is also perceived to be very specialized, even if you work outside the bank and insurance verticals.

There are exit opportunities, but it’s difficult to break into non-FIG roles if you stick around too long, and there’s far less private equity activity than in most other industries.

So, if your main life goal is to work at a private equity mega-fund as a generalist, FIG is not the right group for you.

But if you want to advise or invest in financial institutions, or you’re planning to work in the group and transfer elsewhere, the Financial Institutions Group should be less of a dungeon and more of a delight.

Want More?

You might be interested in Investment Banking League Tables: Neutral Arbiter of Bank Rankings or Marketing Manipulation?

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Why is Goldman FIG revered as a top group on the street when MS/JPM have similar deal flow and aren’t close in terms of exits/prestige/reputation?

No idea really. I assume it is just a bit of the overall Goldman Sachs prestige spilling over into other industries. I’m not sure I would say that Goldman FIG is a “top group” compared to some others… since you will have more specialized/limited exits from any FIG team no matter what you do.

Can I learn the FIG valuation courses if I am working under FIG Credit Risk?

From 2013 through 2022, you’ve sent us about 20 separate emails via the BIWS help desk / contact form, purchased multiple products, and in each case, requested a refund. So, my question to you is: Why bother?

If you’ve already tried the BIWS courses and found they are not for you for whatever reason, why would you keep purchasing them? It’s just going to result in you not being satisfied, requesting another refund, and then sending us more questions.

I think you should find a course or training method that better fits your preferred learning style or find something closer to your current career.

Hi Brian,

Thanks for your article! I am doing fund accounting in one BB back office currently, and I passed CFA. How do you assess the possibility of transferring from back office to FIG? And could you please suggest what else I can do to improve my competitiveness? Thanks very much

It’s always difficult to move from the back office to a front office IB role no matter what you do. The CFA will provide a marginal boost, but much less of a boost than relevant deal experience or something like a top MBA program.

Your basic options are: 1) Network around internally and push for this transfer at your current firm. 2) Leave your firm and find a more relevant role elsewhere, such as at an independent valuation firm, Big 4 firm, corporate bank, or something similar, and then move into IB from there. 3) Complete a Master’s or MBA degree at a top program and use that to get in.

I would probably go with option #2 here, and if you don’t gain much traction applying for these other roles that are closer to deal/front office experience, consider another degree (type/timing depends on your years of work experience pre-degree).

Can FIG banker eventually go into asset management/wealth management in 2nd stock market? I discover my interest in AM after 5 years in investment banking…

Sure, but I think AM would be a lot harder to get into than WM due to the small industry size and lower turnover. We don’t normally list WM as an “exit opportunity” because the assumption is that it’s easier and less competitive to get into than IB… so if you can get into banking, wealth management should be an easier option.