Investment Banking League Tables: Neutral Arbiter of Bank Rankings or Marketing Manipulation?

If you want to find investment banking league tables, it’s easy: Google the term and add a specific region, industry, or year you’re interested in:

“Investment banking league tables us healthcare [20XX]”

For faster results, use Image Search to scan the results and find relevant-looking tables.

Plenty of mainstream sites and services like the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, Refinitiv, and Merger Market publish these league tables in different formats each year.

This article is not about specific league tables but the motivation behind them and when they’re useful and not so useful.

These tables come up in online discussions/arguments about ranking the top investment banks, but people often take them too seriously.

League tables have their uses, but you should interpret them as marketing – mixed with some real-world data and support:

What Are Investment Banking League Tables?

Investment Banking League Tables Definition: IB league tables “rank” banks over specific periods based on their involvement in a certain industry, region, or deal type, such as M&A transactions or equity offerings.

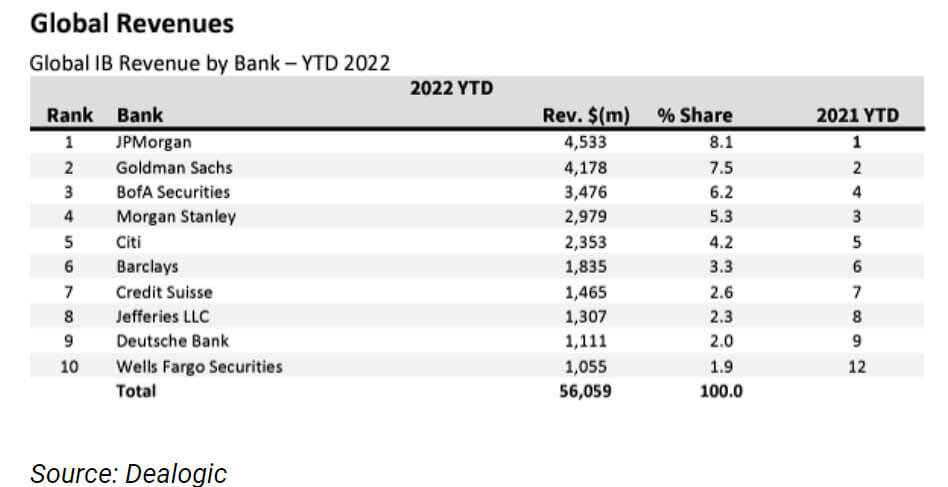

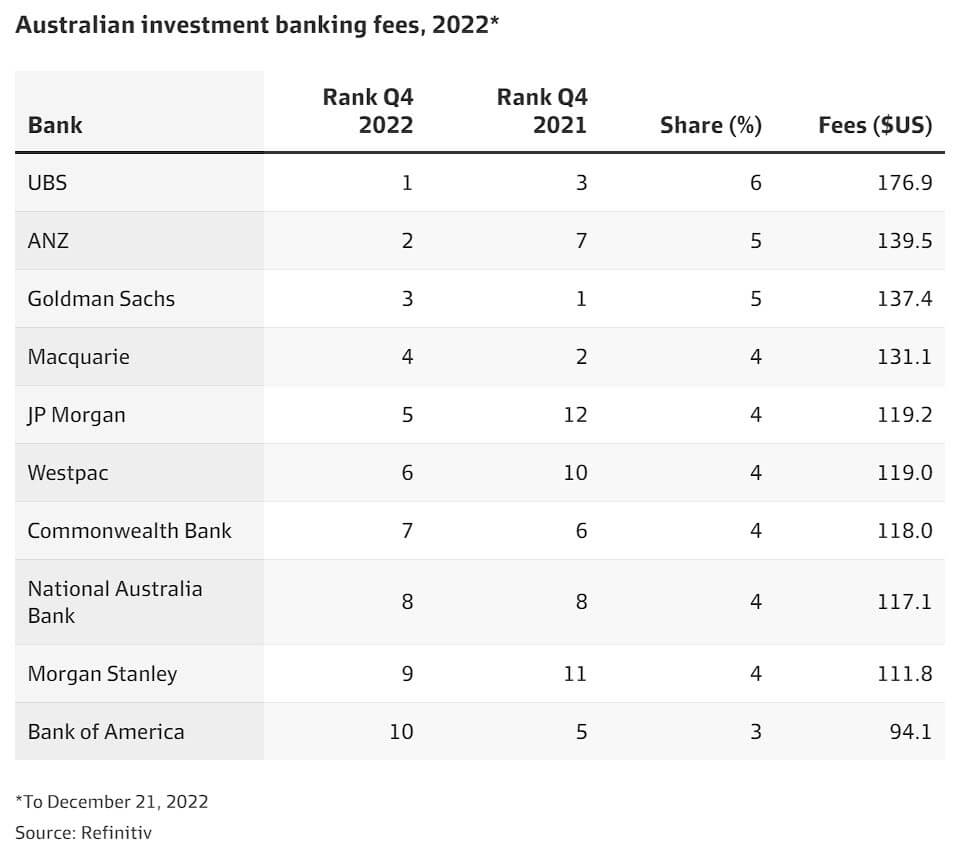

Here are a few examples, which took approximately 1.6 seconds to find via Google Image Search:

Sources: Seeking Alpha | Australian Financial Review | Private Banker International

These “rankings” might be based on deal value (e.g., $50 billion in total announced deals), deal count (e.g., 50 transactions), or fees (e.g., $200 million in advisory fees)

League tables also exist for law firms to show their involvement in deals, but we’re focusing on IB league tables here.

Why Are Investment Banking League Tables Useful?

You might think that league tables are useful for answering questions such as:

- Which industry group or product group should you join? Industrials at DB or healthcare at MS? Aerospace & defense at Jefferies or restructuring at Houlihan Lokey?

- If you get multiple offers in different regions, which one should you accept? BofA in NY or GS in Chicago? JPM in London or MS in NY? Guggenheim in NY or Qatalyst in SF?

To some extent, league tables can answer these questions.

For example, if Bank A hasn’t made the top 10 in the past ~3 years, while Bank B has consistently been #1 or #2, Bank A likely has more deal flow in this region or industry.

That translates into a better experience as a junior banker and more deals you can discuss in future interviews.

But investment banking league tables are not designed for you, the job seeker.

League tables are primarily marketing tools for banks.

These tables exist so that banks can state in their pitch books: “Look! We’re #1 in Deal Type X or Region Y.”

To set up the data for these claims, IB Analysts often spend hours “cutting the data” to make their bank look better.

The usual approach is to start with league table data from external sources and figure out screening criteria to eliminate deals that don’t support the narrative.

Here are a few examples from an Inovalon pitch book by JPM:

These specific examples are reasonable since the screens are minimal: year and industry.

But you’ll also see plenty of contrived cuts with the criteria selected solely to make the bank look better:

- Healthcare M&A Deals Worth Between $400 Million and $1 Billion Over the 17 Months

- Industrial Equity Offerings Worth Between $100 Million and $500 Million with > 50% Domestic Institutional Buyers Over the Past 9 Months

- SPAC Deals Worth At Least $300 Million with A-List Celebrity Sponsors and Over 1,000 Retail Investors Who Lost Money

(OK, the last one is a joke, but I think you get the idea.)

Why Can’t You Take Investment Banking League Tables That Seriously?

For marketing purposes, the flaws are obvious: you can always cut deal lists a certain way to tell whatever story you want.

If you see a league table with a contrived screen like the ones above, you should take it even less seriously than the rest of the pitch book.

But the flaws may be less obvious with league tables produced by 3rd party services.

Here are just a few of the many problems:

Problem #1: Disagreements Over Deal Counts and Volumes

If you gather league table data from different sources, you can find cases with 20 – 30% discrepancies, which is enough to shift the rankings.

There’s a specific example of this issue in the AFR article linked to above.

This happens for various reasons, but most of it comes down to the search and “credit” processes.

For example, one service might rely on publicly announced deals with clearly stated deal sizes, while another might dig deeper or use bank-provided data.

And with large deals with multiple banks involved, the standards for “crediting” banks vary.

The easiest solution is to credit each bank equally, but this is problematic when the banks play very different roles (see below).

Canceled and heavily modified deals create even more issues with the deal count and volume stats.

Problem #2: Undisclosed or Ambiguous Deal Sizes

This one is especially an issue in restructuring because many deal sizes are undisclosed, and even when the information is public, the exact price may be ambiguous.

For example, if a bank advised a $1 billion Enterprise Value company on restructuring $600 million of Senior Notes, should the deal size be $600 million? $1 billion? $400 million?

If there was a debt-for-equity swap, should the deal size be based on the debt balance or the estimated value of the new equity?

Undisclosed deal sizes are also an issue in middle- and lower-middle-market league tables because plenty of small companies get acquired for undisclosed prices.

Earnouts also present a challenge: if a company gets acquired for $1 billion, with an additional $500 million if it achieves its financial goals, do you use $1 billion or $1.5 billion for the size?

Or do you split the difference and say $1.25 billion?

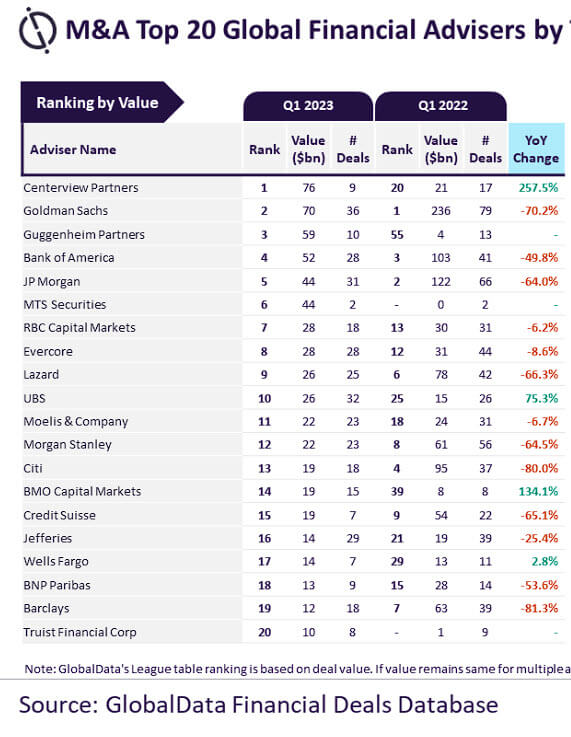

Problem #3: Deal Count, Dollar Volume, or Advisory Fees?

The most common approaches in IB league tables are to rank banks by either deal count or dollar volume.

So, if JPM announced $50 billion worth of M&A deals last year, while GS announced $45 billion, JPM ranks #1, and GS ranks #2 based on dollar volume.

But if JPM advised on 15 deals while GS advised on 17 deals, and you use deal count rather than dollar volume, GS ranks #1.

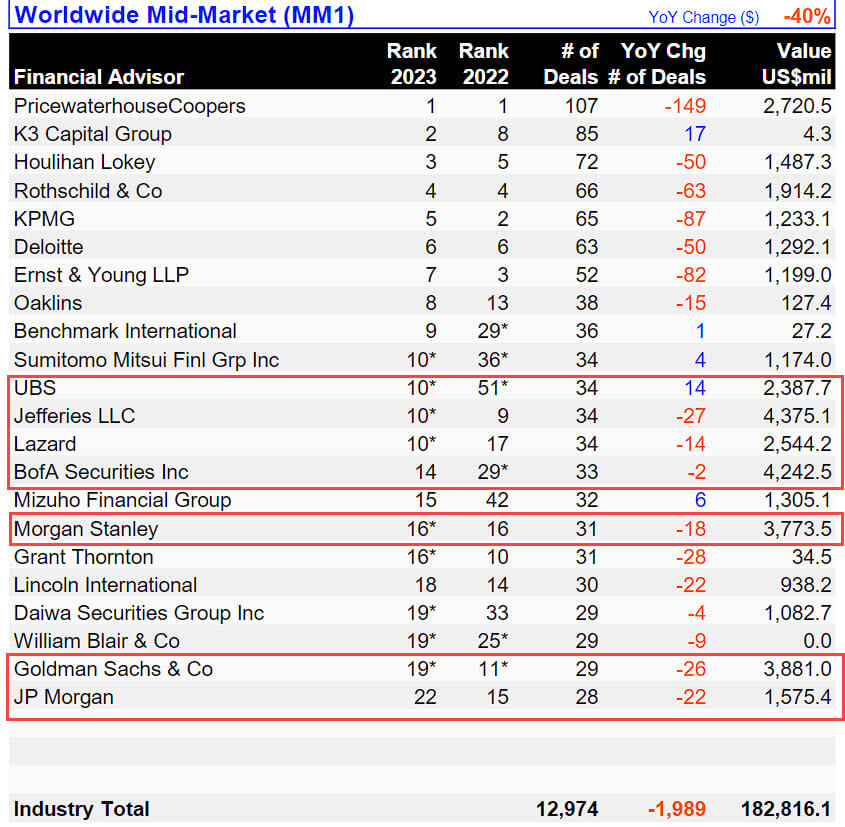

You can see the problems with ranking banks by deal count if you look at a table like this one for middle-market deals:

Yes, PricewaterhouseCoopers is #1, but would you ever want to work in investment banking at PwC over Houlihan Lokey, Rothschild, Jefferies, Lazard, BofA, or UBS?

No, of course not – because they mostly advise on small deals and issue Fairness Opinions rather than executing full deals.

Because of these issues, it’s always better to go by dollar volume, not deal count.

That said, both these methods are flawed because they do not account for the fees.

The fees give the best indication of how much work the bank did and, therefore, the experience you got by working on the deal.

Unfortunately, finding fee breakouts for individual deals is difficult, so region and industry-specific tables based on fees are rare.

Problem #4: The Advisers’ Roles

A bank can act in different capacities in a single deal, and not all roles are created equal:

- It might be the “lead adviser” in an M&A deal, or it might just issue a Fairness Opinion near the end for a small fee.

- It might advise on all aspects of the transaction, or it might just provide the debt financing required to close the deal (e.g., Leveraged Finance).

- In an equity deal (ECM), the bank could be the bookrunner or a co-manager.

- In restructuring deals, the bank might advise the debtor (the company) or the creditor(s).

Issuing a Fairness Opinion or co-managing a deal requires far less work than executing the entire deal from start to finish.

So, banks that act in these lesser roles should receive less credit in the league tables…

…but that’s typically not how it works.

Banks do everything they can to “jump into” large deals at the last minute and get at least some credit, since they know they can claim the entire deal value.

Problem #5: The Senior Banker Shuffle

Finally, while league tables can be decent guides over short periods, they tend to be less accurate over long periods (5-10+ years) because turnover is so high.

Some senior bankers stay at one firm for a long time, but most move around a few times in their careers, and when they do, their clients come with them.

Sometimes, large banks even hire entire teams from other banks to get these client lists.

Banks like to pretend that clients are loyal to their brand, but decision-makers at companies are more often loyal to individual bankers, whom they’ve gotten to know over many years.

So, When Are Investment Banking League Tables Useful?

League tables have their uses, but they are not oracles of truth because of all these issues.

If you want to use them to decide on a bank, group, or region, I would recommend the following:

- Review the Past ~2-3 Years of Data – Results in a single year or quarter are not always representative, so you want at least a few years of data. But I don’t think it’s useful to go back 10 or even 5 years because the landscape changes too much over that time frame.

- Be As Specific As Possible – For example, find tables that screen by at least industry or region rather than “global” rankings. Maybe you can’t find a “European tech M&A” league table, but even a European M&A or tech M&A league table would be far more useful than a global, all-industry table.

- Don’t Use League Tables to Make Close Decisions – If Bank A has been #5 over the past few years, while Bank B has been #3, you should not pick a Bank B internship offer on this basis. These numbers are so close that you’d be better off using the team, cultural fit, and other factors to decide.

Further Reading About Investment Banking League Tables

If you want to learn more about the uses, drawbacks, and effects of investment banking league tables, please see:

- M&A investment bank rankings are in a league of their own for flaws (Financial Times)

- The Effects of Investment Banking Rankings: Evidence from M&A League Tables (Academic Paper)

And if you ever meet someone who relies on league tables to argue for a specific bank ranking, run far away and ignore everything else they say.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews