Industrials Investment Banking: The Complete Guide

After all, you’ll work on a wide variety of deals, you won’t get pigeonholed, and you’ll have a broad set of exit opportunities.

Better yet, the sector is so diverse that even if one vertical isn’t doing well, you can always move into something else.

So, what’s not to love about industrials?

Well… not too much, but there are a few downsides.

But let’s start with an overview of the sector, key drivers, deals, and more:

Investment Banking Industry Groups: Industrials

Investment banks usually divide their teams into industry groups and product groups.

Industry groups execute different deal types (M&A, equity, and debt) within a single industry, while product groups execute a single deal type across many industries.

Industrials is an example of a broad industry group.

It includes many different verticals that may not appear to be “related” at first glance, but most of them share a few traits:

- Companies make machinery and large physical products, transport those products, or service those products.

- Customers are usually corporations or governments rather than consumers.

- The sector is highly sensitive to overall economic conditions and broad macro factors such as the availability of credit and corporate profitability.

The “standard” divisions in Industrials Investment Banking are:

- Capital Goods: Aerospace & Defense, Building Products, Construction and Engineering, Electrical Equipment, Industrial Conglomerates, Machinery, and Trading Companies.

- Transportation: Air Freight and Logistics, Airlines, Marine, Road and Rail, and Transportation Infrastructure.

- Commercial and Professional Services: What it sounds like! Only two divisions here.

Banks do not necessarily follow this industry classification in their group structures, but they tend to divide their industrial groups into Capital Goods and Transportation in some way.

We’ve covered many of these sub-groups in separate articles: business services investment banking, transportation investment banking, maritime/shipping investment banking, and construction & engineering investment banking.

So, we’ll focus more on the Capital Goods segment in this article, touch on Transportation, and discuss a few of the most interesting verticals, such as Aerospace & Defense and Airlines.

What Do You Do as an Analyst or Associate in the Industrials Group?

When you work on pitch books, you’ll be responsible for the industry research, data on comparable companies and transactions, and the historical and projected financials for the potential client.

If it’s a debt or equity pitch, the capital markets bankers will provide information on the markets and recent deals, and if it’s an M&A pitch, the M&A bankers will include recent M&A market trends and build more specific transaction models.

The accounting and valuation methodologies for industrials companies are not specialized in the same way they are for oil & gas companies or commercial banks.

So, the 3-statement models, valuations, and transaction models you build could apply to a range of industries if you change around the revenue and expense drivers.

When a live deal takes place, you’ll be responsible for the company and industry background and other qualitative factors in the CIM, teaser, or sales team memos, and you’ll take the lead on the 3-statement model for the company.

Bankers in the other groups might add the transactional elements to the model and handle more specific tasks, such as modeling a divestiture or earn-out.

You’ll work on quite a few M&A and debt deals in this sector because many companies are mature, with stable cash flows, and mature industries tend to consolidate over time.

Many private equity firms also focus on industrials, so you’ll see a good number of leveraged buyouts, bolt-on acquisitions, and dividend recaps.

Equity deals are somewhat less common in this sector because there are fewer high-growth companies than there are in, say, technology or healthcare.

Industrials Investment Banking Trends and Drivers

Since they tend to manufacture expensive items that last for years, they can suffer disproportionately if corporate customers lose confidence and start delaying their purchases.

They’re also highly sensitive to commodity and raw material prices, so their margins tend to fluctuate significantly.

But commodities are a double-edged sword because many industrial firms also sell to commodities-related businesses, so higher prices might increase both revenue and expenses.

To analyze industrials companies, you need to think about factors such as:

- Customers: Governments? Corporations? How diversified or concentrated are the customers by industry and geography?

- Supply Chain: How efficient is the company, how many suppliers does it depend on, and how easily can it adjust its supply chain to respond to changes in demand?

- Upgrade Cycles: How often do corporations and governments need to replace or upgrade their equipment? How much do they spend on it in annual budgets?

- Distribution Networks: What are the company’s channels? Does it rely on just one distributor, such as Home Depot, or is it highly diversified?

- Production Costs: What drives the firm’s production costs, and where are its factories located? How does it compare to peer companies?

- Barriers to Entry: Does the firm have barriers to entry, such as customer loyalty, high startup costs, patents, or legal/regulatory hurdles, that give it pricing power?

- Competition: Sometimes a firm has clear competitors, but in other cases, it’s a bit murky. For example, many Defense companies bid against their competitors to win projects but then sub-contract out parts of projects to those same competitors.

Let’s now move to companies and key drivers for a few specific verticals within industrials:

Capital Goods

Representative Large, Global, Public Companies: Caterpillar (U.S.), Saint-Gobain (France), ITOCHU (Japan), Marubeni (Japan), Mitsui (Japan), Toyota Tsusho (Japan), Sumitomo (Japan), and AB Volvo (Sweden).

Capital Goods companies make machinery, such as airplanes, tractors, and power generators, as well as building products and electrical equipment.

These companies are capital-intensive and driven by construction spending, corporate capital expenditures, and infrastructure spending by governments.

One of the most widely-watched metrics here is Caterpillar’s 3-month rolling machine sales data, or “monthly retail statistics.”

NOTE: I’m excluding Construction & Engineering companies here because we covered the sector in a separate article on construction & engineering investment banking.

If you’re wondering where all the Chinese companies are, many of the biggest ones are in that segment: China State Construction Engineering, China Railway Construction, and China Communications Construction, for example.

Aerospace & Defense

Representative Large, Global, Public Companies: Boeing (U.S.) and Airbus (Europe) operate a duopoly here, but other companies in this segment manufacture specific parts or systems of planes: United Technologies (U.S.), Lockheed Martin (U.S.), General Dynamics (U.S.), Northrop Grumman (U.S.), and Raytheon (U.S.), for example.

This segment is interesting because part of it – Defense – is recession-resistant and arguably even countercyclical. It tends to outperform in bear markets, unlike almost everything else in industrials.

That’s because product demand depends on government spending, which doesn’t necessarily follow business cycles; it’s tied to military and wartime needs.

The disadvantage is that government contracts have very, very, very long lead times and are subject to drawn-out bidding processes.

A Defense company is unlikely to delivery an amazing quarter of surprise revenue growth, but its sales are often stable over the long term.

On the Aerospace side, companies depend on growth in air travel, airline profitability, and the need to upgrade and replace older planes.

Research & development is incredibly risky because if a company “guesses wrong” about what the market wants, it could suffer for years or decades.

You saw this with Airbus and its A380, which cost a fortune but failed to catch on in the way the company wanted.

Key metrics include the order backlog, capacity utilization, passenger traffic, and the growth of new airline routes.

For Defense companies, the types of contracted projects in the backlog, such as fixed-price vs. time-and-materials vs. cost-reimbursable, matter a lot.

Transportation

Representative Large, Global, Public Companies: UPS (U.S.), Deutsche Post (Germany), FedEx (U.S.), Mærsk (Denmark), Xiamen Xiangyu (China), East Japan Railway, Bollore (France), Financière de l’Odet (France), Union Pacific (U.S.), and Kuehne + Nagel (Switzerland).

These companies benefit from strong economic growth and global trade, and they’re hurt by lower growth expectation, falling trade volumes, and higher oil prices.

Shipping companies are driven by the demand for food, commodities, oil, and petrochemicals, and trucking and rail companies often transport commodities and basic materials.

For these companies, key metrics include the average length of haul, the average age of the fleet, and fleet utilization.

You can use those to determine their operational efficiency and cash flow trends.

For more details, see our articles on transportation investment banking and maritime/shipping investment banking.

Airlines

Representative Large, Global, Public Companies: American Airlines, Delta (U.S.), United (U.S.), Deutsche Lufthansa (Germany), Air France-KLM, IAG (owners of British Airways and Iberia), Southwest Airlines (U.S.), China Southern Airlines, and Air China.

Airlines are different from almost everything else in industrials because they’re driven by consumers, not government or corporate spending.

Yes, business travel still plays a significant role, but the majority of passengers travel for leisure and are sensitive to prices – so airline pricing can make a huge impact on demand and profitability.

Low-cost carriers made a big splash in the market by figuring this out and offering dirt-cheap ticket prices in exchange for a miserable onboard experience and tons of upsells.

Many airlines hedge their fuel needs, but they’re still sensitive to rising oil prices because they can’t pass on the entire increased cost onto consumers.

Some of the key metrics for airlines include:

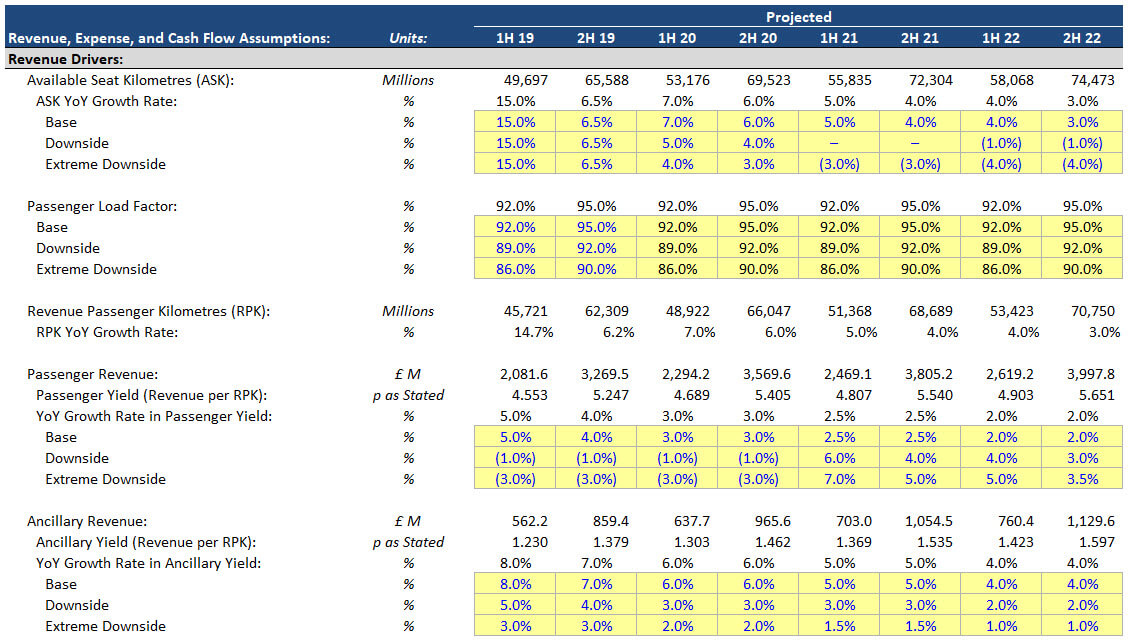

- Available Seat Miles (ASM) or Available Seat Kilometers (ASK)

- Load Factor

- Revenue Passenger Miles (RSM) or Revenue Passenger Kilometers (RSK)

- Fuel Expense and Operating Expense per ASM or ASK

- Passenger Yield

Available Seat Miles are like an airline’s “total capacity.”

If it has 10 planes that each fly 2,000 miles per day, and each plane has 300 seats, then the daily ASM are 10 * 2,000 * 300 = 6 million, and the annual ASM are 6 million * 365 = 2.2 billion.

The Load Factor tells you the percentage of seats that are occupied, and Revenue Passenger Miles = Available Seat Miles * Load Factor.

So, if this airline’s Load Factor is 85%, Revenue Passenger Miles = 2.2 billion * 85% = 1.9 billion.

The Passenger Yield tells you how much the airline makes for each RSM or RPK, and Passenger Revenue = Passenger Yield * RSM.

If this airline’s Passenger Yield is $0.10, then its Passenger Revenue = $0.10 * 1.9 billion = $190 million.

You also factor in revenue from cargo, baggage fees, and other sources, but those are the basics.

Here are example revenue projections for EasyJet, taken from one of the case studies in our Advanced Financial Modeling course:

Advanced Financial Modeling

Learn more complex "on the job" investment banking models and complete private equity, hedge fund, and credit case studies to win buy-side job offers.

learn moreIndustrial Conglomerates

Representative Large, Global, Public Companies: Mitsubishi Corporation (Japan), General Electric (U.S.) (for now…), Siemens (Germany), SK Holdings (South Korea), CITIC (China), Hanwha (South Korea), Honeywell (U.S.), and 3M (U.S.).

The last category here does a bit of everything.

These companies tend to operate across many verticals within industrials, and sometimes they even cross into other sectors, such as technology, media, finance, and healthcare.

They often acquire smaller companies, divest divisions, and operate in such a range of geographies and markets that it’s tough to make definitive statements about them.

To analyze these companies, you need to look at each division and do a sum-of-the-parts analysis, factoring in corporate overhead.

Industrials Investment Banking League Tables: The Top Banks

Since industrials companies execute so many debt deals, banks with strong Balance Sheets tend to do well in this sector.

Look at the U.S., European, and global league tables, and you’ll see firms like Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BAML), JP Morgan (JPM), Citi (C), and Credit Suisse (CS) near the top.

Goldman Sachs (GS) is often in the #1 spot in this sector – even though it’s less of a commercial bank than the others.

In terms of middle-market and boutique firms, Lazard, Lincoln, and Baird often do well.

Specific groups at other firms, such as Houlihan Lokey’s Aerospace & Defense group in Washington, D.C., are also well-known in this sector.

Industrials Investment Banking Deals and Valuations

You use common valuation multiples such as TEV / EBITDA, P / E, and TEV / Revenue to value companies, and the usual DCF model works well.

The only real exception is in the maritime/shipping group within Transportation, but even there, the differences aren’t that big.

It’s important to understand lease accounting in this sector since companies own assets directly, lease them, and do everything in between.

Here are a few examples of deals, valuations, and investor presentations in different verticals:

Capital Goods:

- ITE Management / American Railcar Industries (Leveraged Buyout) – Western Reserve Partners

- Univar / Nexeo – Goldman Sachs and Moelis & Company

Aerospace & Defense:

- Harris Corporation / L3 Technologies – Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs

- Science Applications International Corporation / Engility – Guggenheim, Morgan Stanley, Citi, and Stone Key Partners

Commercial and Professional Services:

Transportation:

Airlines:

In the U.S., most airlines consolidated a long time ago – only one fairly recent, major transaction came to mind:

Industrials Investment Banking Exit Opportunities

Since you work on a broad range of deals across many verticals, your exit opportunities in this group are also quite broad.

Financial sponsors lead many deals, so many industrials investment bankers head into private equity.

Corporate development is also a possibility, as are hedge funds.

The only exit opportunity that you don’t have a great shot at is venture capital and, along with it, startups.

There are some startups in the industrials sector, but they are usually still technology-based companies – such as software companies that help manufacturing firms improve their supply chains.

The Industrials Sector: For Further Reading

To learn more about the industry, we recommend the following resources:

- News: Industry Today

- News: Industry Week

- Industry Reports: Baird’s Industrial Reports

- Industry Reports from Big 4 Firms: PwC, More PwC, Deloitte, EY, and KPMG

- Industry Reports from Banks: “Deciphering Defense, an Industry Primer” (Google it to find the latest version)

- Books: Fisher Investments on Industrials

Industrials Investment Banking Pros and Cons

Summing up everything above, here are the pros and cons of the group:

Pros:

- You gain broad exposure to different deal types and verticals, so your exit opportunities will be quite broad.

- You won’t pigeonhole yourself because the accounting, valuation, and financial modeling are not specialized.

- You gain a lot of exposure to financial sponsors because many of the companies are mature, have stable cash flows, and are good buyout targets.

- There’s significant debt and M&A activity and relatively less equity deal flow.

- The sector is so diverse that you can move into a different vertical with more deal flow if your group slows down.

Cons:

- The sector is highly sensitive to economic activity, so if there’s a recession, deal flow will slow down significantly… except for Defense companies, maybe. It’s the complete opposite of a “defensive” sector, like healthcare or utilities.

- The group doesn’t position you perfectly for every exit opportunity – venture capital, startups, or tech-related roles would be more difficult, for example.

But that’s a short list of cons and a much longer list of pros – which is why you can’t go wrong with industrials investment banking.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Hi Brian, is Raymond James a reputable one in Industrials sector, in terms of exit opportunities to top tier PE? And how do you rank RJ, Scotiabank and Piper Sandler? Thank you very much!

Raymond James is a good firm but not ideal for getting into PE because it’s considered a middle market bank by most people, which means you have less access to exit opportunities than people at larger banks. The firms you mentioned are all about the same ranking-wise, so it depends on the industry focus and team you prefer.

Hi Brian, is Divisified Industrials the same as Industrials?

Yes