The Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: Useful Categories in the Finance Industry, or Marketing Hype?

The buy-side vs. sell-side distinction/debate is interesting because it happens on the internet and in real life.

With other topics – such as “target schools” or “elite boutiques” – few people use the terms in-person.

In fact, it would be quite weird if you spoke one of these terms aloud in an interview.

But everyone from headhunters to bankers to interviewers uses the terms “buy-side” and “sell-side,” and most people put themselves in one category or the other.

Unfortunately, the ubiquity of these terms has also made them more confusing.

The definitions are a bit murky, and they get even murkier the more you dig into them.

But before explaining the problems, let’s start with the basic definitions:

The Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side Definitions

Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side Definition: In the finance industry, “buy-side firms” raise money from institutions and wealthy individuals and invest on their behalf, profiting from management fees, performance fees, or both; “sell-side firms” earn money from commissions charged to facilitate deals and to sell, market, and trade equity, debt, and other securities.

The best examples of buy-side firms are private equity firms, hedge funds, and venture capital firms.

They all raise money from Limited Partners (LPs), such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, and insurers, and invest in companies and securities.

They earn money from a management fee charged on their assets under management (AUM) and a performance fee, often 20% of the profits above a certain hurdle rate.

The best example of a sell-side firm is an investment bank across most industry and product groups, such as healthcare, technology, and M&A.

Equity research and sales & trading are also in the “sell-side” category since they mostly earn money from fees paid for their services (research and market-making).

Within an industry like commercial real estate, a real estate brokerage is a sell-side firm since it charges a commission on the property sales it facilitates.

But real estate private equity firms and real estate debt funds are both buy-side firms since they earn money based on management fees and investment performance.

The Problems with the Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side Distinction

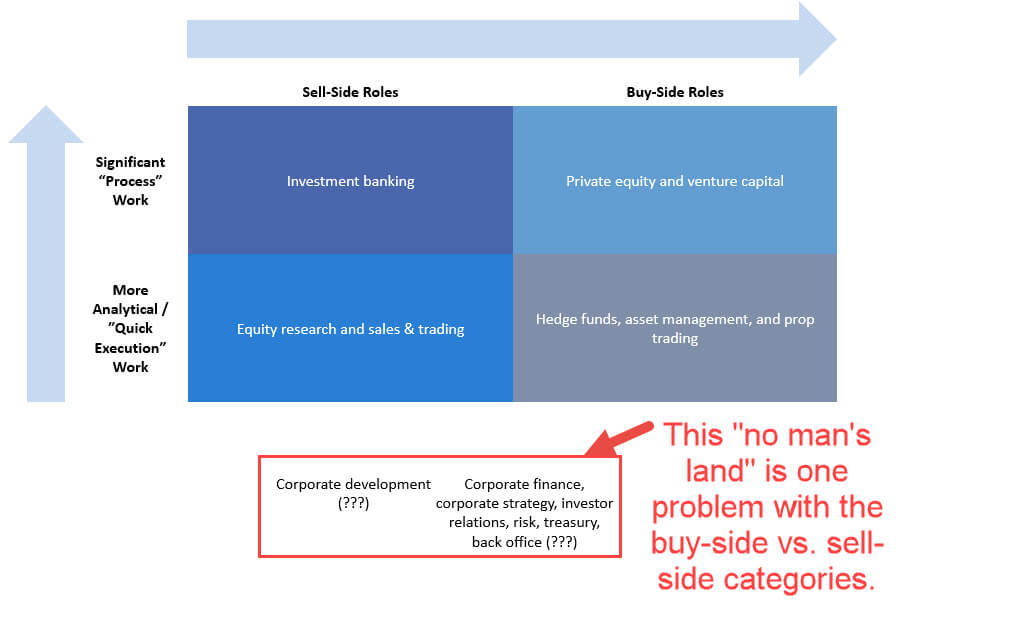

These categories are helpful for simple examples, but once you go beyond them, you’ll quickly find there are two big issues:

- The Grey Zone – Many buy-side firms do not charge performance fees, so the link between performance, profits, and compensation is less direct.

- Misfits – Many finance roles do not fit into either category; the classic examples are corporate finance and corporate development at normal companies.

With the first point, mutual funds, Canadian pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds fall into this category of “raise capital and invest it, but charge no performance fees or much lower fees than PE/HF firms.”

Something like private banking is also in this “Grey Zone” because private bankers invest on their clients’ behalf, but they typically charge fees based on AUM – and most people do not consider PB a traditional buy-side role.

On the markets side, prop trading firms are another “Grey Zone” example because most act as market-makers rather than directional traders (i.e., they don’t profit from investing in stocks and betting that prices will go up or down).

But the compensation ceiling is higher than in sell-side roles because prop traders can use strategies that traders at banks cannot and are more lightly regulated.

On the second point – “misfits” – corporate finance professionals at normal companies do not raise or invest money and do not charge commissions.

Their compensation is relatively fixed, based on internal company budgets – but most people still consider corporate finance an alternative to banking or an exit opportunity.

Corporate development is even tougher to classify because you analyze deals and acquire companies, but you’re not investing outside capital raised from LPs, and you don’t benefit directly from the performance of acquired companies.

The Alternative Categories: Deals vs. Public Markets vs. Support

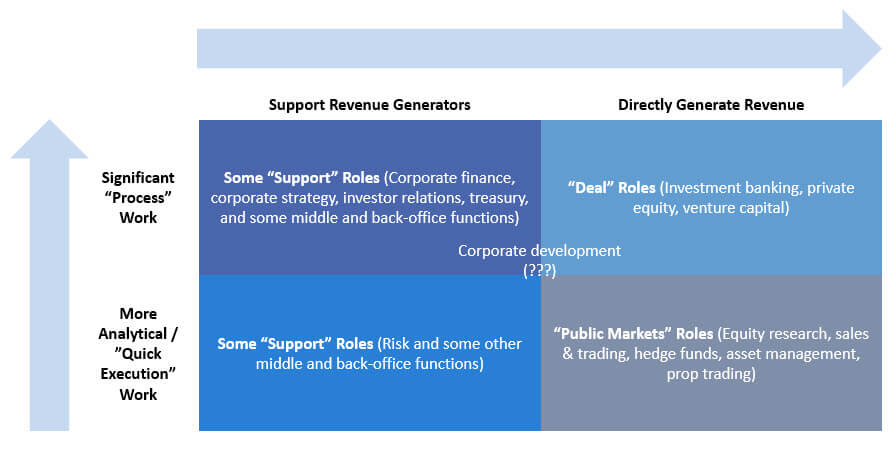

Because of these issues, it might be more useful to put finance jobs into three main categories:

- “Deal” Roles: Investment banking, private equity, venture capital, and… maybe corporate development (?? – see below).

- “Public Markets” Roles: Equity research, sales & trading, hedge funds, prop trading, and asset management.

- “Support” Roles: Corporate finance, corporate strategy, investor relations, risk management, treasury, and… arguably some back-office jobs (??).

The key differences are:

- Revenue Generation – In “Deal” and “Public Markets” roles, your work generates revenue directly or has the potential to do so in the future (e.g., from a successful investment). In “Support” roles, you do not generate revenue directly but support the employees who do.

- Process vs. Analysis/Execution – “Deal” and “Support” roles involve a lot more “process work” (documents, presentations, due diligence, etc.), while “Public Markets” roles are more about thinking and acting quickly and getting the timing correct.

If I were a management consultant, I would create the following 2×2 matrix to illustrate the issues with the normal buy-side vs. sell-side categories:

My 2×2 matrix for the Deal vs. Public Markets vs. Support categories would look more like this:

This doesn’t solve everything because corporate development’s category is still unclear, but the others are easier to classify.

In the rest of this article, I’ll focus on the buy-side vs. sell-side and deals vs. public markets differences, but I’ll add a few references to the support roles where appropriate.

The Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: The Work and Skills Required

At the junior level, the Deals vs. Public Markets vs. Support distinction is more relevant for the work and skill set.

In “Deal” roles, skills such as financial modeling, creating presentations and memos, and reviewing documents to conduct due diligence are very important.

In “Public Markets” roles, there is still some financial modeling or technical analysis, but it tends to be more ad hoc and dependent on timing and making quick decisions.

So, you’ll still value companies in a role like equity research or at a long/short equity hedge fund, but these will often be “quick valuations” to take advantage of a certain market move or company update.

(But hedge funds vary widely, and some firms do thorough analyses based on deep, months-long research processes.)

In “Support” roles, the work is driven by monthly processes in areas like corporate finance, and it’s more about projects, research, and long-term planning in something like strategy.

All that said, the buy-side vs. sell-side categories do create differences in the work and skill sets.

The main one is that you’ll have to use far more critical thinking in buy-side roles because your job is to generate new investment ideas, think through the risks, and develop growth opportunities – even as a junior employee.

By contrast, much of the work in sell-side roles consists of following management or consensus estimates and making your model match up.

You learn the mechanics but not necessarily the thought process.

And while some buy-side funds have bureaucracy and annoying rules, sell-side roles care far more about points like the proper font sizes, alignment, and color-coding in Excel models.

Buy-side roles care more about the results (i.e., money made) than the cosmetics.

Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: Hours, Lifestyle, and Stress

If you look at this in terms of Deals vs. Public Markets vs. Support, “Deal” roles have less predictable hours, with plenty of spikes up and down based on what different buyers, sellers, and target companies are requesting.

Public Markets roles have more predictable hours each day, but the intensity of that day is quite high, with little downtime (see: sales & trading vs. investment banking).

You will be busy following companies, updating your models and analysis, reading the news, and generating new ideas constantly.

Support roles are somewhere in between, depending on the exact job and company type.

On average, you will work the longest hours in “Deal” roles because more work, documents, and deliverables are required to close large deals involving entire companies.

The buy-side vs. sell-side categories also make a difference here.

In sell-side roles, most of the stress comes from responding to clients and other bankers and juggling the pitches, ongoing deals, and “random requests” that come in.

In buy-side roles, the stress is more about making the correct investment decisions and second-guessing yourself as the prices go up… and down… and then up again.

In roles like private equity and corporate development, there’s less market-related stress, but there’s longer-term anxiety because it takes years to determine if an acquisition performed as planned.

In short, the stress in sell-side roles has a higher frequency, but the stress in buy-side roles has a higher amplitude.

Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: Salaries and Bonuses

People always focus on the fact that the ceiling is much higher in buy-side roles since you may capture some of the upside in deals or investments that perform well.

Then, they look at famous hedge fund managers who earn $100 million+ per year and use that to argue that “the buy-side pays more.”

They are correct that the most senior, top-performing buy-side professionals earn far more than Managing Directors in areas like investment banking and sales & trading.

But they’re also cherry-picking data and ignoring the ~99% of professionals in the industry who earn an order of magnitude less – and the various buy-side roles with no performance fees or much lower fees.

If you consider these issues and use compensation data from real surveys, you’ll find that the average pay depends more on your specific job, performance, and seniority than it does on the buy-side vs. sell-side distinction.

For example, bankers out-earn most VCs even though IB is a sell-side role.

But the compensation ceiling for global macro traders at large hedge funds is much higher than it is for sell-side traders at banks, and the average pay is also higher.

If you stay in the industry for, say, 15-20 years, and you get promoted into a senior position at a firm that performs well, you’ll almost certainly earn more in many buy-side roles.

This happens due to the performance fees and carried interest in private equity and hedge funds; in other areas, it’s a closer call because of low/no performance fees.

The Deals vs. Public Markets vs. Support distinction makes little difference in this category other than the fact that “Support” roles tend to pay much less because they’re not directly linked to revenue generated.

Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: Advancement

Once again, this point depends more on the specific industry and firm type and less on the buy-side vs. sell-side distinction.

For example, advancement at a multi-manager hedge fund is a structured, predictable process based on performance, while advancement at a small, single-manager fund is more random and subject to the whims of the Founder.

On average, though, it is a bit more “straightforward” to advance in sell-side roles.

If you do the job decently and avoid mistakes, you will probably get promoted up to some level.

Also, turnover tends to be quite high, with many MDs lasting only a few years, so new spots always open.

By contrast, buy-side advancement is often trickier because senior people never want to leave.

You see this especially with the large, multi-manager hedge funds and private equity mega-funds, but it happens even at smaller/newer places.

Also, the standards for advancing are higher because you must make money or have the potential to do so.

By contrast, you could get promoted to the mid-levels in banking if you’re a good “project manager” and haven’t necessarily proven your ability to win clients or deals.

Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: Exit Opportunities

The buy-side vs. sell-side categories are less relevant here because the exit opportunities depend mostly on your skill set and track record.

Put simply, it is extremely difficult to go from a “Deal” role into a “Public Markets” role or vice versa, regardless of whether that role is buy-side or sell-side.

You could move from either one into a “Support” role, but going from a “Support” role into one of these categories is also difficult.

If you look at the articles on this site about IB and PE exit opportunities, you’ll see they’re similar because the work and skill sets are similar.

By contrast, most “Public Markets” roles require a sharper but narrower skill set, so the exit opportunities are also more specific.

Many equity research professionals can win other research roles or join long/short equity hedge funds, but it’s much rarer to go into IB or PE roles.

And many traders can join global macro funds or groups that use trading-like strategies such as convertible bond arbitrage – but you won’t see them joining PE firms.

The bottom line is that if the exit opportunities are your top concern, you should try to start in a “Deals” role.

If you already know what you want to do and have no interest in keeping your options open, “Public Markets” roles are fine if you can win a good offer at a reputable firm.

The Buy-Side vs. Sell-Side: Final Thoughts

People casually toss these terms around online and in real-life discussions, but they’re a bit deceptive once you go below the surface.

Summing up everything above, the three most important points are:

- Your specific job matters more than whether it’s “buy-side” or “sell-side” – Similar to the investment banking vs. private equity question, don’t assume that one offer is better than another just because it’s a “buy-side job.”

- At the junior levels, the “Deals” vs. “Public Markets” vs. “Support” categories may be more relevant – This isn’t true for all aspects of the job, but it applies to the exit opportunities, skill set, and hours/lifestyle.

- The buy-side compensation ceiling is higher, but it takes a long time to reach that ceiling – You won’t necessarily see a huge difference on a 3-5-year timeline, but if you stay in the industry for 10-15+ years and your firm performs well, you should earn significantly more at a PE firm or hedge fund.

If you understand these points, you should be well-prepared the next time someone starts using the buy-side vs. sell-side talking points – whether in real life or an online comment thread filled with angry rants and insults.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Hey Brian,

Great read.

Hello from India. Recently graduated from a pretty decent undergraduate university (one of the best in the country) with an honours degree in accounting/finance. Also have CFA L1. Previously interned in consulting at Big 4, fundamental research group at a hedge fund, and halfway through an internship at an independent valuation firm. Trying to break into IB, what would your advice be? Options I can think of are to try and convert the valuation internship, or apply to an IB role, or study further, maybe UK. (Wondering if I’d be considered a strong enough candidate for either?) Thanks!

Your best option in India is usually to leave and apply in Europe or the U.S. because the Indian market is very small and tough to break into without attending one of the top ~2 IIMs and getting in right out of that. If you’ve already graduated, I’m not sure your chances are great, though you do have some very good experience.

If you don’t want to move abroad, another option might be to think about boutique investment banks in India. This interview is from a few years ago now, but there’s a pretty good account of a startup-focused bank here:

https://mergersandinquisitions.com/startup-investment-banks-india/

As You usually mention about the Exit opportunities after working for Investment Banking Firm’s for several years. I have noticed that many Investment bankers in my home country India start there own startups, and there are several successful startups such as, Nykaa, Bharatpay and the people behind this companies are Ex-Investment banker’s. So, is it that working as an investment banker can make a person that capable of starting his or her own successful business. What’s your take on this ?

In general, IB is not a good background for most startups / entrepreneurial ventures because you don’t gain any sales skills at the junior levels, and starting a company is mostly about sales. There are some exceptions where domain expertise can help, e.g., with a fintech startup or something geared toward financial services companies as customers, but working as an Analyst or Associate in IB has almost nothing to do with, say, starting an e-commerce company.

Most people who start successful companies after working in IB could have done it without the IB experience and usually just picked banking because it was a “safe” option at the time.