Long/Short Equity: Full Guide to the Most Accessible Hedge Fund Strategy

What do a burned-out investment banker, an avid member of r/WallStreetBets, a retired couple in Florida, and Bill Ackman all have in common?

They all think they can make a fortune buying and selling stocks; in other words, they’re fans of the long/short equity strategy.

The difference is that only one of them has a proven track record demonstrating their skill.

When the average person thinks of hedge funds, long/short equity is often the first thing that comes to mind.

It seems like a simple strategy: buy a stock if you think it’s going up and sell or short a stock if you think it’s going down.

The basic idea is simpler than other hedge fund strategies, but it gets more complex when you think about the entire portfolio and risk management:

What is Long/Short Equity?

Long/Short Equity Definition: Long/short equity is an investment strategy in which hedge funds buy stocks that are expected to appreciate (“long”) and borrow shares to sell stocks that are expected to decrease (“short”); by buying and selling stocks at the same time, the strategy aims to profit from individual mispriced securities while reducing overall market risk.

Probably 90% of hedge fund stock pitches use long/short equity or related strategies.

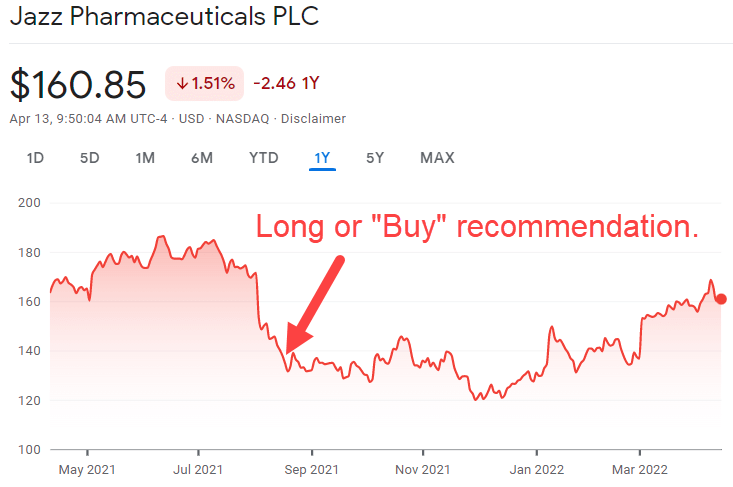

Here’s an example of a “Long” pitch for Jazz Pharmaceuticals [JAZZ], which we recommended buying at around $130 (full case study in our Advanced Financial Modeling course):

Advanced Financial Modeling

Learn more complex "on the job" investment banking models and complete private equity, hedge fund, and credit case studies to win buy-side job offers.

learn more

We recommended a long position because:

- The market overreacted to a bad earnings report with a 25% decrease in sales for the company’s key product (Xyrem), ignoring how most patients were being migrated to a similar but newer-and-better drug.

- The market underestimated the revenue potential of its replacement drug Xywav, acquired drugs Epidiolex, Zepzelca, and a few Phase 2 and 3 trial drugs.

- And favorable catalysts in the next 6-12 months included a possible lawsuit settlement in the company’s favor, additional approved indications for the newer drugs, and possible advancements to Phase 3 trials (earnings announcements might reveal some of these).

- Finally, the company seemed significantly undervalued based on the multiples from comparable companies, precedent transactions, and the DCF, and we felt the risk factors (competition, integration of acquired company GW Pharma, and failed clinical trials) were manageable.

A long-only asset manager (i.e., at a mutual fund) looking at this same company would have two options: buy JAZZ or do nothing.

On the other hand, a long/short equity hedge fund might have the following additional options:

- Long JAZZ and short a biopharma index or ETF to reduce the industry risk.

- Buy call options on JAZZ rather than buying the stock outright.

- Long JAZZ and also buy put options on the company in case the stock moves in the other direction.

- Long JAZZ and also long a direct competitor if an upcoming lawsuit or drug approval will hurt one company and harm the other.

Most hedge funds using this strategy have a long bias, i.e., they devote more capital to long positions than short positions.

For example, if a hedge fund has $1 billion in assets under management (AUM), it might put $700 million into long positions and $300 million into short positions.

Its gross exposure would be $700 + $300 million = $1 billion, and its net exposure would be $700 – $300 million = $400 million.

If the fund uses leverage, i.e., it borrows money to amplify its returns, it might have $1.4 billion in long positions and $600 million in short positions.

In that case, its gross exposure would be $2 billion, or 200% of its AUM, and its net exposure would be $800 million.

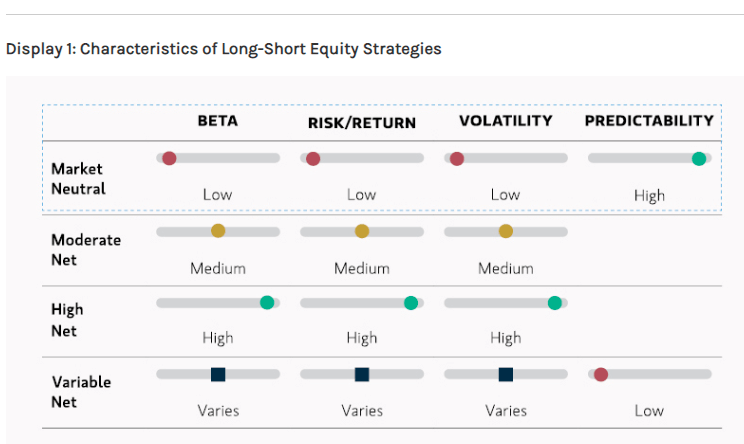

Some funds even use market-neutral strategies in which the long positions equal the short positions, resulting in a net exposure of 0% (or close to it).

This graphic from Morgan Stanley sums up the strategies quite well:

What Makes Long/Short Equity Hedge Funds Different?

Since “equity strategies” account for over 40% of all active hedge funds, there’s a huge variety in investment styles.

Funds might focus on different industries or geographies, and each fund might target a different gross and net exposure, # positions per portfolio, holding period, and more.

A group with 100 positions and holding periods of weeks or months will be much more like “trading,” while one with 10 positions and multi-year holding periods will be much more like long-term investing.

There’s also the single-manager vs. multi-manager question and the degree to which the fund uses quant strategies rather than discretionary ones.

In general, many single-manager funds using long/short equity do deep dives into company fundamentals by reading through the filings, earnings calls, and other material, and even doing on-the-ground research (channel checks).

By contrast, at multi-manager funds, long/short equity is more about getting quarters right so the fund can profit right after earnings are announced; expect less detailed research and more updates and tweaks of your existing views.

As you move up to the Senior Analyst and PM levels, the work shifts from company analysis and valuation into risk management, position-sizing, and monitoring the entire portfolio.

For example, if one of your long positions increases 25% right after a positive earnings call, do you sell it right away, sell a smaller percentage, or keep holding?

Do you limit each position based on size, price vs. value, industry weightings, or other metrics?

How much of a loss would you take before closing a position, and how frequently do you rebalance?

And what do you require from Analysts who pitch ideas to you?

Long/Short Equity Investment Analysis

Most discretionary strategies follow the same steps to determine whether a stock is valued appropriately: build a valuation based on multiples, the DCF, or another intrinsic value-based methodology, such as the NAV model for REITs.

In most cases, you don’t even need a full 3-statement model; a “cash flow only” DCF with a few revenue and expense drivers is sufficient.

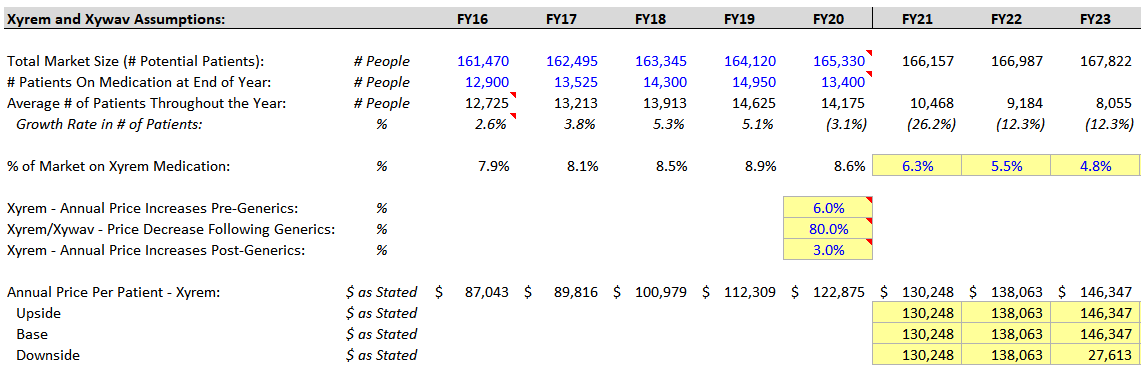

Sometimes, these drivers can get quite complicated, especially for a company with many different products and unique assumptions for each one:

Idea generation varies widely, but it might consist of a “watch list” of companies in your sector, suggestions from your PM, and ideas you get from reading, research, and the news.

For example, let’s say you watch an interview about ecologically sustainable buildings in urban areas.

That gets you thinking about materials companies that might benefit from this trend, so you research the sector and run a screen looking for companies with FCF yields >= 10%, revenue growth >= 10%, and TEV / EBITDA multiples <= 15x.

You find a few companies that might be undervalued and then read through their filings and recent earnings calls to narrow your list.

Other funds might use different screening criteria or no screen and do qualitative research to find promising names.

Coming up with differentiated assumptions might involve speaking with industry experts, doing channel checks, and reading views that are outside the mainstream/consensus.

For example, maybe you visit a few stores of one retail company and observe foot traffic and the approximate number of purchases per store per day.

This data leads you to believe that the company’s quarterly sales could be far below expectations, so you use more pessimistic assumptions to value the company and bet that the stock price will drop when earnings are announced.

The Top Long/Short Equity Hedge Funds

Virtually every multi-manager hedge fund uses long/short equity strategies, so the list of “top funds” depends on whether you count these diversified platform funds (e.g., Bridgewater and Millennium) or smaller funds specializing in L/S equity.

Also, the list depends on whether you rank by funds by AUM or performance and the time frame.

Ignoring these nuances, however, a few hedge funds known for their long/short equity strategies include Point72, Viking Global Investors, Select Equity, Maverick Capital, Lone Pine Capital, and Davidson Kempner.

If you go to London, you can add names like Marshall Wace, Man Group, Lansdowne, and Egerton Capital to the list.

And if you also include long-only hedge funds, you can add names like Baupost Group.

Recruiting Into Long/Short Equity Funds: Who Gets In?

The short answer is “investment bankers, equity research professionals, and a mix of people from other finance roles.”

But I wanted specific data, so I did a quick review of 32 professionals at long/short equity hedge funds in my LinkedIn network and got the following results for typical pre-hedge fund backgrounds:

- Equity Research: 10 (~31%)

- Investment Banking: 8 (~25%)

- Asset Management or Other Buy-Side Markets Roles: 5 (~16%)

- Other Hedge Funds: 4 (~13%)

- Private Equity or Growth Equity: 2 (~6%)

- Sales & Trading: 1 (~3%)

- Management Consulting: 1 (~3%)

- Other (Big 4): 1 (~3%)

Investment banking and equity research are, by far, the most common backgrounds, but there are other options.

The main issue with asset management is that there are few entry-level roles at the big firms, and turnover is low, so it doesn’t offer the easiest path into hedge funds.

If you want to do this, brand names (e.g., Fidelity) help, as does a top MBA.

Getting in from a sales & trading role is also quite challenging because cash equities trading has been automated, and even before the automation, traders rarely did “fundamental analysis.”

But you could certainly find an execution trading role at a L/S equity fund, especially if you’ve had experience with derivatives.

Traditionally, hedge funds focused on recruiting experienced candidates, but that has changed as firms like Point72 have made a big push into undergrad recruiting.

Overall, long/short equity is one of the more feasible hedge fund strategies to break into straight out of university because there are many ways to get relevant experience.

And if you can win an offer at one of the big hedge funds, it’s nice to skip IB or ER and move straight into investing.

On the other hand, you might want to think twice about an offer from a smaller/startup hedge fund (think: $100 million in AUM) because you may not get the networking or training opportunities you would at a bank or larger fund.

As always, hedge fund recruiting tends to be more off-cycle and unstructured than PE recruiting, and most funds want to hire people with immediate start dates.

Long/Short Equity Interviews and Case Studies

Hedge fund interviews focus on your investment ideas and what you think about different strategies and sectors, and long/short equity funds are no different.

But there are a few specific points to note:

- Stock Pitches – You need at least 1 Long idea and 1 Short idea, and ideally 3-4 total ideas. You do not need detailed models, but you need investment theses that differ from mainstream views and some support for your numbers.

- Case Studies and Modeling Tests – It’s common to present your stock pitches in the first round and then complete a case study and present your findings in person in later rounds. Case studies involving 3-statement models are very common (e.g., “Take this company’s 10-K, build a model, and make an investment recommendation”).

If you want to improve your performance, I recommend practicing with strict time limits.

In other words, don’t spend 1-2 weeks doing a deep dive into one company to build a model.

Instead, pick a random company and give yourself 3-4 hours to build a simple DCF, value it with a few multiples, and make a quick long or short recommendation.

This time limit forces you to focus on the 2-3 most important points rather than getting lost in unnecessary details.

Long/Short Equity Careers, Hours, and Compensation

Most of these points have more to do with factors like single-manager vs. multi-manager, fund size, and your PM’s preferences than the long/short equity strategy.

In general, though, at many long/short equity funds, the attitude is: “Do whatever you want during the day; just generate ideas that make us money!”

The good news is that means you’re more likely to get exposed to the entire investment process, so it can be easier to move up if you perform well.

The bad news is that means the hours tend to be longer and more stressful, especially if it’s late in the year and you’ve been underperforming.

It’s probably a 60-70 hour per week job at the average fund, with more stress on the multi-manager side but also more of a clear advancement path.

Long/Short Equity Exit Opportunities

If you leave this path, you’ll have some decent exit opportunities, but not as many as you would get from IB or PE. A few options include:

- Long-Only Asset Managers – Yes, you’ll take a pay cut (~50%?), but you’ll have more of a life, less stress, and you might get to work in a much lower-cost location.

- Other Hedge Funds – It can be difficult to move to a completely different strategy, such as global macro or credit, but you have a better chance with a more relevant one, such as a merger arbitrage group that focuses on pre-announced deals.

- Corporate Finance/Strategy or Investor Relations – If you’ve specialized in a certain sector or know a lot about one specific company, you could potentially move to the corporate side for even less stress, shorter hours, and lower pay.

You could also move back into IB or ER, but that’s unusual if you’re already on the buy-side.

Starting a hedge fund is also an option, but you normally need a solid 5-10-year track record at an established fund to do that.

Deal-based roles such as corporate development, private equity, and venture capital are possible but not likely exits – unless you’ve already had experience in one of them.

The long/short equity skill set is too different, and if you don’t have experience coordinating lawyers/accountants/lenders, sifting through data rooms, and prodding management teams to get answers, you won’t be competitive.

Additional Resources

Almost every investment book ever written relates to long/short equity in some way, so I’ll recommend the following:

- Value Investors Club – “Ideas” – They only post older ideas for free, but there are many great examples here.

- SumZero – You can post ideas to gain access or pay directly to view samples.

- Books and letters from famous or successful investors (David Einhorn, Joel Greenblatt, Joseph Nicholas, Peter Lynch, Ben Graham, Seth Klarman, Warren Buffett’s letters, etc.).

Long/Short Equity Hedge Funds: Final Thoughts

Long/short equity strategies are more accessible and easier to learn and explain than many others in the hedge funds space.

But that’s a double-edged sword because it also means more people can use the strategy, more candidates compete for jobs at these funds, and, once you start working at one, that it’s more difficult to find mispriced securities.

So, don’t assume that you need to work in long/short equity because it’s such a common strategy.

You could position yourself for many other paths by joining the right team at a bank, or you could skip banking entirely and go the public markets route from the start.

Many people claim that discretionary long/short equity is “dying” because performance has been poor since 2008, central banks have distorted the markets, and quants have taken over.

There is some truth to this claim, as long/short equity performed better when the hedge fund industry was much younger (the 80s and 90s).

And even discretionary strategies are becoming more data-oriented, with many funds now employing data science teams and “quantamental” strategies.

So, it’s fair to say that long/short equity has changed over time and become less appealing vs. other strategies.

But I don’t think it will die anytime soon – at least, not as long as burned-out bankers, Reddit users, retired couples in Florida, and Bill Ackman all have money to invest.

Want More?

If you liked this article, you might be interested in Hedge Fund Strategies: What’s the Fastest Path to $1 Billion? or The Venture Capital Case Study: What to Expect and How to Survive.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews