Hedge Fund Strategies: What’s the Fastest Path to $1 Billion?

When it comes to hedge fund strategies, most articles focus on explaining what each strategy means and how the trading styles differ.

That’s fine, but it leaves other important questions unanswered:

- Which skill set does each hedge fund strategy require?

- Who wins offers at different types of hedge funds? Do bankers, equity research professionals, or traders have higher chances at certain types of funds?

- Oh, and which strategy pays the most? Are there long-term career differences?

We’ll delve into these points here, but let’s start with the basics:

What is a Hedge Fund?

In short, hedge funds are investment funds that raise capital from institutional and accredited investors and then invest it in financial assets – usually liquid, publicly-traded assets.

They seek out investments that will beat the overall market or reduce risk while earning market returns, and they use a wider array of strategies than those available to traditional mutual funds and asset management firms.

In exchange for that, they also charge higher fees than mutual funds, including management fees on assets under management and a percentage of the investment profits, called “carry.”

Hedge funds and private equity are similar in some ways, but PE firms focus on buying and selling entire companies, not individual securities, and they recruit slightly different types of candidates. For more, see our coverage of hedge funds vs. private equity.

How Do You Categorize Hedge Fund Strategies?

You could classify hedge funds according to dozens of criteria, but many of these criteria are not useful when searching for funds.

For example, maybe you want a fund with a specific “culture,” such as a laid-back environment with quirky, artistic people.

That’s great, but good luck searching for funds that match that one on LinkedIn, Capital IQ, and other online databases.

More realistic, searchable criteria include:

- Asset Class: Equities? Fixed Income? Options? Commodities? Currencies? Convertibles? Private assets? Crypto? NFTs? Elon Musk’s Tweets? A mix of all of these?

- Industry Focus: Technology? Healthcare? Energy? Generalist?

- Investment Style: Directional? Event-driven? Relative value (arbitrage)? Global macro?

- Automation Level: Discretionary? Systematic (“quant”)? Something in between?

- Fund Model: Single-manager or multi-manager?

- Size of Fund: Under $1 billion AUM? $1 – 5 billion? Over $10 billion?

In most cases, you should start by thinking about the asset class because that correlates most closely with your ability to work at a fund.

In other words, if you’re on the rates trading desk, you’re in a good position to trade sovereign bonds or interest rate derivatives at hedge funds that use those products in their strategies.

On the other hand, you’re not in a good position to work at a long/short equity fund because you do not analyze and value individual companies.

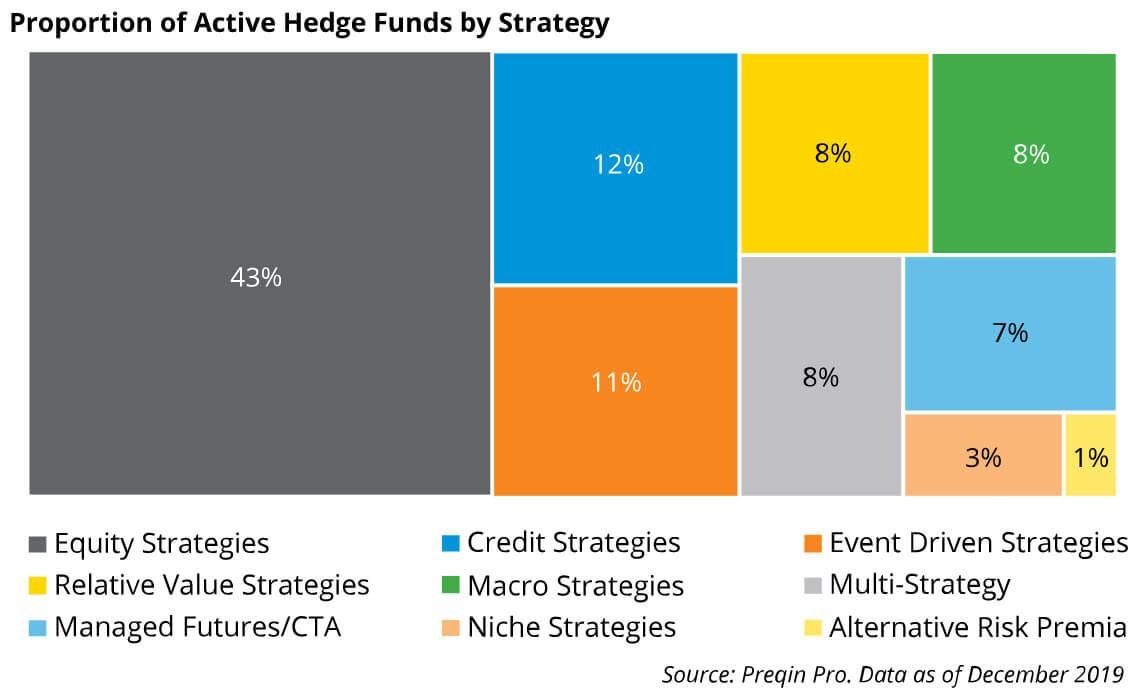

Here’s how Preqin divides up the hedge fund universe:

“Equity strategies” usually comprise the biggest percentage, so let’s start there:

Hedge Fund Strategy #1: Equity

Description: Equity strategies are based on stocks and their derivatives, such as call options and put options.

The most basic strategy is to take long positions in stocks that appear to be undervalued and take short positions in stocks that appear to be overvalued.

A “long” position means that the fund buys shares with the expectation that the price will rise.

A “short” position means that the fund borrows shares, sells the shares at a higher price, and then attempts to buy them back at a lower price.

Options-based strategies sometimes fall into this category, but funds using equity strategies tend to use options as components of their strategies, such as to reduce risk and limit losses.

Sub-Categories: The most well-known strategy here is long/short equity, which attempts to long and short a variety of stocks, usually targeting a certain net exposure for the portfolio.

For example, a fund with 70% long positions and 30% short positions has a 40% net exposure, assuming that it does not use leverage.

Many funds have a long bias, as in this example, while others are market-neutral (net exposure close to 0), and still others have a short bias.

On the more extreme ends, there are also long-only and short-only funds in this category. A true short-only strategy is extremely risky because the potential losses are unlimited, so this tends to be rare.

The industry focus varies widely, and you’ll see everything from narrow sector specialists (e.g., biotech companies using one specific technology) to generalist funds and groups.

Example Trade: Coke looks cheap, so you buy $100,000 worth of Coke shares, anticipating that its share price will rise.

To hedge, you could short a similar company that looks too expensive (e.g., Pepsi) or an entire ETF, such as one that tracks consumer/retail companies.

Clearly, you make money if Coke rises and Pepsi (or the ETF) falls.

But if you’re incorrect about one part of this trade, you could still make money if you’ve gotten the relative values correct.

For example, if Coke rises by 30% and Pepsi rises by 25%, you’re still up by 5%, even though you were incorrect about Pepsi falling.

Required Skill Set: For non-quant roles, you need to understand accounting, financial statement analysis, valuation, and financial modeling very well because you’ll be valuing companies all the time.

At single-manager funds, you’ll have to do deep dives into companies via channel checks and proprietary research, and at multi-manager funds, you’ll need to be skilled at juggling many companies, updating models based on recent results, and getting quarters right.

Most Likely Candidates: Plenty of investment bankers join these types of funds, but equity research professionals and investment analysts from traditional asset management firms and mutual funds also end up here.

Traders are less well-positioned for these roles unless the fund uses options heavily or the trader wants to execute trades rather than making investment decisions.

Examples of Dedicated Funds in This Category: Viking Global Investors, Select Equity, Baupost Group, Egerton Capital, Maverick Capital, and Lone Pine Capital.

Hedge Fund Strategy #2: Credit

Description: Credit strategies are similar to equity strategies in that they involve taking long and short positions in securities, but they are based on debt securities and their derivatives instead (e.g., corporate bonds, municipal bonds, sovereign bonds, credit default swaps, etc.).

So, you spend less time valuing entire companies and more time evaluating the downside risk of specific types of debt – since the upside is capped for most fixed income.

“Downside risk” could include risks from default, changes in prevailing interest rates, and illiquidity.

With non-distressed credit, you’re unlikely to find securities that are hugely mispriced. So, many funds here aim for consistent singles and doubles rather than that elusive home run.

Sub-Categories: The most basic strategies are simple long credit and short credit, and some groups focus on specific types of debt, such as mortgage-backed or asset-backed securities or mezzanine or other high-yield debt.

Not many firms focus on investment-grade debt because it’s more difficult to find pricing discrepancies, and coupon rates are low.

There are also collateralized loan obligation (CLO) funds and market-neutral funds.

Example Trade: Unsecured Bond A of Company X has a coupon rate of 7% and trades at 90% of par value, with a maturity in 3 years. You believe it’s undervalued because the company’s credit default risk is much lower than the market expects, and a full repayment is likely.

You long Unsecured Bond A, with approximate, potential annualized returns of 7% + (10% / 3) = ~10%.

To hedge the default risk, you also purchase credit default swaps (CDS) on the bond in case the company is unable to repay the principal in 3 years.

Required Skill Set: You must know bond math (e.g., how to approximate the Yield to Maturity) and the specifics of different securities, such as interest rate swaps and credit default swaps for hedging, very well.

There is some traditional financial modeling work because you need 3-statement models to evaluate companies’ covenants in downside scenarios, and even valuation comes up because you need it to assess the recovery percentages for different tranches of debt.

That said, DCF-based valuation is somewhat less important, and so are M&A and LBO modeling.

Also, while this is not a universal rule, many credit funds take a “breadth, not depth” approach, so you’ll need to feel comfortable covering many names rather than doing a deep dive into only a few.

Most Likely Candidates: Some investment bankers and research professionals (more on the credit research side) move into funds that use credit strategies, but traders with experience on desks like rates trading and distressed debt are also competitive.

It also depends on whether the fund uses more of a “research” approach or a “trading” approach; both are possible in this area.

Examples of Dedicated Funds in This Category: Capula Investment Management, III Capital, Benefit Street Partners, Symmetry Investments, Silver Point Capital, and Saba Capital.

Hedge Fund Strategy #3: Event-Driven

Description: In a sense, all hedge funds use “event-driven” strategies because catalysts are key components of all investments – even a simple long/short stock pitch.

But event-driven funds rely even more heavily on specific events, such as mergers and acquisitions, spin-offs, divestitures, bankruptcies, restructurings, recapitalizations, IPOs, scams SPACs, and even simple earnings calls.

When one of these events occurs, the market often misprices one or more securities related to the event, especially in the early stages.

And the more complex the event, the higher the likelihood of a mispriced security.

This strategy is also more difficult to “automate” than others because certain events have limited historical data.

Often, hedge funds using these strategies will long one security and short another security in the same company’s capital structure to profit from the mispricing.

Sub-Categories: Examples include special situations (betting on spin-offs, divestitures, M&A, IPOs, litigation, and so on), distressed debt (see all our coverage – distressed private equity and distressed debt trading), and merger arbitrage.

There are also general “opportunistic” strategies that wait for events and adapt as needed without focusing on one specific event type.

Finally, activist funds that purchase significant stakes in public companies to influence corporate strategy also fall into this category.

Example Trade: Company A is rumored to be announcing a 100% stock acquisition of Company B within the next week.

Company A trades at $100 / share, Company B trades at $50 / share, and Company A might pay a 20% premium for Company B ($60 / share).

You believe the deal will go through, but that Company A is also overpaying for Company B by about $5 per share of its own stock price.

So, you long Company B’s stock since it should move up closer to $60 / share once the deal is announced, and you short Company A’s stock, expecting it to fall once the deal is announced and the market reacts poorly.

Required Skill Set: You need to know company valuation and transaction modeling very well, and for distressed debt, all the details of the restructuring and bankruptcy processes, including the long, boring legal documents.

Most Likely Candidates: Bankers with solid M&A and Restructuring experience often end up at these funds; it’s more difficult if you’re coming from the capital markets side.

You’re not as well-positioned for these funds if you have an equity research or sales & trading background because you don’t work on transactions in those roles (exceptions apply for certain desks).

Examples of Dedicated Funds in This Category: Elliott Management, York Capital, Third Point, Varde Partners, ValueAct Capital, Trian Partners, and Starboard Value.

Hedge Fund Strategy #4: Relative Value (Arbitrage)

Description: Funds using these strategies invest based on price discrepancies between closely related securities, such as a company’s stock and its convertible bonds.

Other examples might include similar debt issuances from the same company or even sovereign bonds with different maturities, such as 2-year vs. 10-year U.S. Treasuries.

In all these cases, the idea is to long one security and short the other. Since they’re closely related, strategies based on these trades tend to have less systemic risk than others.

Sub-Categories: The most famous strategy In this category is convertible bond arbitrage, in which the hedge fund will long the bonds and short the company’s equity, or vice versa, based on whichever one is underpriced.

But there are other examples, such as fixed income arbitrage and general “capital structure arbitrage,” and on the quant side, statistical arbitrage.

Example Trade: Company A has convertible bonds with a coupon rate of 0.50% and a conversion price of $20.

When Company A first issued the bonds, its share price was $15, but now it has risen to around $20, so the convertible bonds are “at the money.”

The delta of the bonds is 50%, so if the underlying share price rises or falls by $1.00, the convertible bonds rise or fall by $0.50.

So, you buy $1,000 of the convertible bonds and short $500 of the company’s shares.

If the stock price rises, the gain on the convertible bonds will exceed the loss from the short position in the company’s shares (and vice versa if the stock price falls).

Required Skill Set: The skills here depend on the securities the fund trades.

You might need more of a “trader’s mindset” if it’s something like convertible bond arbitrage or sovereign bond trading, but more of the corporate finance/valuation mindset if it’s more of an all-equity strategy.

Most Likely Candidates: Traders have an advantage for these roles because in practice, most relative value funds use strategies that are based on something other than equities.

Also, any strategy that’s based on volatility – like convertible bond arbitrage – will favor traders because bankers and research professionals tend to know little about it.

Examples of Dedicated Funds in This Category: Pine River Capital, Garda Capital, Context Capital, Polygon Global Partners, Glazer Capital, and Blue Diamond Asset Management (it’s difficult to find many dedicated funds in this category because most groups are part of multi-strategy firms).

Hedge Fund Strategy #5: (Global) Macro

Description: Unlike everything else on this list, global macro strategies aim to profit from broad market moves, not from the values of individual stocks, bonds, or derivatives changing.

This means that macro-based funds and groups could potentially invest in currencies, commodities, equities, fixed income, futures, forwards, and more.

The analysis is also much broader and must include fiscal, monetary, and trade policy, as well as geopolitical events.

Sub-Categories: The sub-categories here seem to be based on the level of automation: discretionary vs. systematic, with some fund types, such as “commodity trading advisors” (CTAs) in the middle.

That said, some funds do focus on specific aspects of global macro, such as interest rates, or specific assets, such as currencies or commodities.

Example Trade: Inflation in Australia is rising, and the central bank (the Royal Bank of Australia, or RBA) has made some noise about raising interest rates.

But you believe it will be slow to do this because the trade surplus is also falling. You believe it’s more likely that the RBA will let the Australian dollar fall against other major currencies to encourage more exports, even at the cost of higher inflation.

So, you short the AUD against the USD, with an expectation that it will fall from $0.75 to $0.70 over a few years.

As a hedge, you also buy call options at $0.78 if you’re wrong, and it moves in the opposite direction.

Required Skill Set: Accounting, corporate finance, valuation, and transaction analysis are almost irrelevant here.

It’s all about your ability to analyze fiscal, monetary, and trade policy and your knowledge of the securities that are linked to them, such as rate products, currencies, commodities, and sovereign bonds.

Most Likely Candidates: As you’ve probably guessed, bankers are not likely candidates for these roles because investment banking has little to do with macro policy.

Instead, traders in highly relevant groups (FX, rates, commodities, etc.) or physical commodities trading firms are the most likely hires.

Occasionally, these funds also hire people with policy backgrounds, such as those who worked on economics in governments, NGOs, or think tanks, under the logic that they’ll be able to analyze global trends more effectively.

Examples of Dedicated Funds in This Category: Brevan Howard, Graham Capital, Caxton Associates, Pharo, Tenaron Capital, Element Capital, and PolarStar.

Wait, What About Crypto?!!! Or Other, More Exotic Strategies?

There are also hedge funds that invest in cryptocurrencies (directly or via derivatives) and other, more “creative” assets: rare art, real estate, insurance products, private companies, private debt, and so on.

I’m not going into detail on them here because many of these “hedge funds” are more like private equity funds or direct lenders, with multi-year holding periods and illiquid assets.

Also, we’ve covered topics such as private debt (direct lending), private companies, and private equity strategies in previous articles.

Finally, some of these assets are so new (crypto) that there’s little substantial information on the strategies, skill sets, or typical candidates.

You should consider these the “Wild West” of hedge funds: potentially promising but also full of risks and fool’s gold.

So… Which Hedge Fund Strategy is Right for You?

The two most common questions here are:

- Which strategy “pays the most”?

- And which one is “the best” for long-term career success?

I’ll start with #1 because it’s easier to answer.

The strategy used by the hedge fund or the team within the fund has almost no correlation with compensation.

Hedge fund compensation is driven by:

- Fund size – The higher the AUM, the more in management fees and the more in potential profits from investments.

- Single-manager vs. multi-manager – Compensation tends to be more structured, with clear links to performance and measurable goals at multi-manager funds, while it’s more discretionary (AKA “random”) at single-manager funds.

- Performance – Earning a 30% return for the year vs. a 5% or 10% return means massively different compensation, especially as you become more senior.

“But wait,” you say, “Aren’t some fund types bigger, and don’t some strategies perform better? Based on that, couldn’t you say that certain strategies are more lucrative?”

Well… kind of, but not really.

It is true that certain strategies perform better than others in specific years, but that changes very quickly.

Quant funds were on fire for a while, but then they had a few years of poor performance, and interest declined. Read about credit hedge funds and activist hedge funds, too.

In terms of size, the biggest funds tend to be multi-strategy, multi-manager funds – the likes of Bridgewater, AQR, Millennium, Citadel, and so on.

Certain strategies, such as activist investing, require more capital and longer lockup periods, which boosts potential compensation.

But I’m not sure there is enough evidence to say that certain strategies result in higher average compensation.

So Many Hedge Fund Strategies… Which One’s Right for You?

Turning to question #2 above, the “best” strategy is the one in which you have the highest chance of winning a job offer.

So, you need to look at your current work experience or expected future work experience and match it to the strategies above.

For example:

- Equity Research and Asset Management: Long/short equity and related strategies are the most natural fit. Credit might also work if you’re on the credit research side.

- Investment Banking: It depends on your group and deal experience, but equity, credit, and event-driven strategies could all be good fits. Event-driven strategies require significant M&A/Restructuring experience, and credit strategies are best if you’re in a group like Leveraged Finance or Restructuring.

- Sales & Trading: Global macro is the most natural fit, but some relative value, credit, and equity strategies could also work if you have experience trading the security in question. You’re not going to go from trading commodities to a distressed debt fund, but you could go from a distressed debt desk to a credit fund.

- Programming/Math/Statistics Background: Quant funds, which exist across most of the strategies above, are the most natural fit.

You’ll never be competitive for all hedge fund strategies, but if you match your background properly, the “best” strategy should be obvious.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Interesting that you said asset management have a shot at getting into long/short equity I would have never knew. Is there a specific role in asset management that long/short equity from hedge funds recruit from?

Investment Analysts (or equivalent title)

Hi Brian,

I’m wondering if an MBA in the future makes sense for my situation.

My background: undergrad in a target university outside of US and non – MBA master in a top B-school outside of US, good but not excellent GPA, currently S&T analyst at a BB.

My Goal: Moving to the US and living there in 3 years time. As for the industry, my first preference would be hedge fund, followed by asset management. Otherwise, I’m ok with staying in S&T or moving to corporate as well. So my main motivation is the geographical aspect, but going to HF would be a bonus.

My question is, does it make sense for me to get an MBA in light of my goals? I know that most S&T people don’t do an MBA, but I can’t think of any other way to move to the US except through maybe internal move. Also, would I have a decent chance at M7 or even H/S/W?

And thanks for the great post btw. :)

I don’t know, I don’t think an MBA is that helpful for a geographic move unless you also want to switch industries into IB or consulting at the same time. And you’re still going to run into visa issues even if you complete the MBA.

I think you’re better off going for an internal transfer so that the bank can handle your work visa and then applying for HF roles at larger funds once you’re already in the country working.

I think you would have a shot at the top programs, but hard to say without knowing more specific details.

Hi Brian,

Do you think DCM analysts will be ideal candidates for credit funds?

Generally no because most HFs do not work with investment-grade debt, and in most DCM roles, you do not do much credit analysis or modeling.

Hi Brian,

I am currently a student at a target university and have had an interest in trading every since middle school. I wanted to know which strategy is best for me, I have provided a quick bio of myself and what I like so that you can use that information to help me figure out the best strategy for me

– I want to be in a fund that is short term focused (max holding time should be 1 month)

– I do not enjoy systematic trading, so the fund should be discretionary.

– I don’t like doing deep-dive fundamental research and prefer trading securities after researching them for a short amount of time.

– I also want to be a generalist.

What you’re describing is more like prop trading, so you should think about firms in that area instead: https://mergersandinquisitions.com/proprietary-trading/

But in prop trading shops isnt it more of a tech job and arent you just executing trades instead of taking your own speculative positions?

It depends completely on the firm type and your position there. Take a look at the previous articles on prop trading.

Hi Brian – thanks for another great article!

I have heard about significant interest in “Tiger Cubs” you mentioned (e.g., Viking, Lone Pine) from bankers and even associates at large private equity funds. Do you know what drives that interest? Is it superior compensation potential/lifestyle? A greater focus on investing versus process management?

My understanding is that, while the strategies may differ among those funds, they tend to be longer-term focused than multi-managers and are better fit for traditional IB/PE backgrounds.

Thanks. I think it’s probably some combination of perceived status/prestige, more “interesting” strategies, and potentially higher compensation based on performance or AUM.

Most single-managers tend to be longer-term focused than multi-managers, so I’m not sure that makes the “Tiger Clubs” different from other single-managers. And yes, most IB/PE candidates would do better at single-managers unless they also happen to be good traders.