Activist Hedge Funds: The Superhero Offspring of Private Equity Firms and Normal Hedge Funds?

If you’re thinking about exit opportunities and can’t decide between private equity and hedge funds, activist hedge funds might be your solution.

Similar to private equity firms, they operate on longer time frames, influence companies’ operations and finances, and might catalyze major changes, such as spin-offs or acquisitions.

And similar to long/short equity hedge funds, they target undervalued and misunderstood companies and profit when the rest of the market catches up.

If you can win an offer at an activist fund, you’ll arguably get some of the most interesting work in the industry.

The main downside is that you might have to clarify what type of “activist” you are – so that you don’t get mobbed by an angry crowd burning down buildings or sociopaths screaming at each other on Twitter:

What is an Activist Hedge Fund?

Activist Hedge Fund Definition: An activist hedge fund accumulates sizable stakes in companies to gain operational/financial influence and persuades Boards and management teams to enact their desired changes; they profit based on increases in companies’ stock prices after these changes take place.

Activist hedge funds are usually classified as “event-driven” within hedge fund strategies, and for good reason.

Long/short equity and credit hedge funds look for mispriced securities with potential catalysts that might change their market prices.

But activist hedge funds create their own catalysts by winning ownership and influence and persuading others to enact the changes they want to see.

The typical approach goes like this:

- Start accumulating a small stake in a public company’s equity.

- Once the stake reaches 5% – which requires disclosure via a 13-D filing in the U.S. – use the filing as an opportunity to announce their position and start their public campaign.

- Release a presentation with the company’s problem(s) and the hedge fund’s proposed solution(s).

- Contact other shareholders and Board members and begin a persuasion campaign to win Board seats at the company and implement the proposed solutions.

The problem could be almost anything, but it’s usually related to:

- Operational Underperformance – For example, peer companies have generated Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) figures of 10-15%, but this company is lagging behind at 5%, which is well below its WACC. Its share price has also been stagnant, while peer companies are up 20-30% over the past few years.

- Corporate Governance and Management – Management is still earning total compensation in-line with teams at better-performing companies, and the Board is filled with sycophantic “insiders” who keep increasing their compensation despite shareholder complaints.

- Undervalued or Misunderstood Assets – One specific division is poorly run and could perform better as an independent entity; the market is penalizing the entire company’s valuation due to this one division dragging down everything else.

- “ESG” – Everyone is going to die from climate change, and this company is the equivalent of Thanos because it doesn’t disclose its carbon emissions or it deviates from the doctrines of the Church of ESG.

The solutions usually involve replacing Board members or executives, divesting assets, changing the capital structure, cutting costs, adopting new strategies, and sometimes selling the entire company.

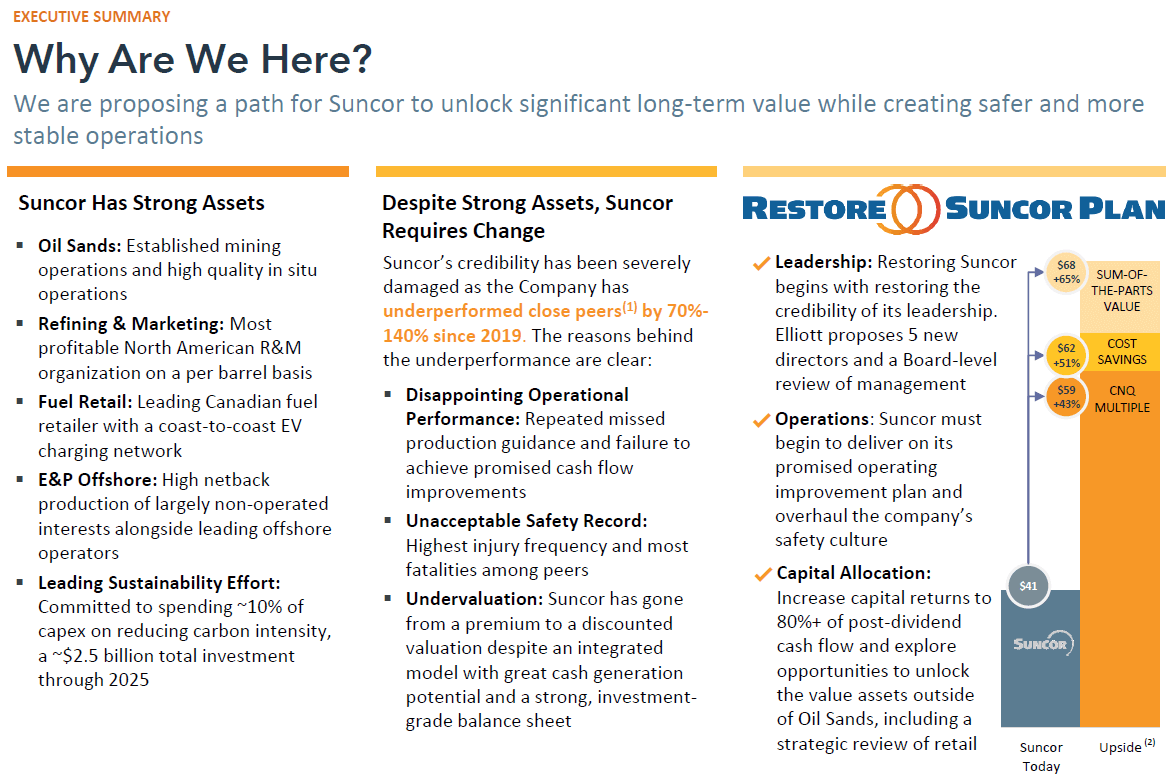

Elliott’s presentation to Suncor after they announced a 3.4% stake in the company has a good example of this structure (click the image for a larger version):

If Elliott succeeds in this campaign, they’ll gain several Board seats, convince other shareholders to support their changes, and sell their stake once Suncor’s stock price is within range of their target price.

Wait, Why Do Company Boards Care About Activist Hedge Funds?

You might now be thinking: “OK, fine, but why does anyone pay attention to activist investors if they have only 5% stakes (or less) when they announce their plans? That shouldn’t be enough ownership to influence the company significantly.”

The answer is:

- Disruption Potential – Even with a small stake, activist hedge funds can be very disruptive to management and the Board because they can win support from other shareholders to stage a proxy fight – and even if they have no chance of winning, it will still consume time and money.

- Even a 5% Stake Could Be Significant – For example, if a public company has no large institutional shareholders, a hedge fund with this type of stake could easily be the top shareholder (or close to it). And even if the public company does have investors like Vanguard, BlackRock, etc., a hedge fund with a 5% stake could still be among the top 5 shareholder groups.

- The Company Has Been Underperforming – When a company’s share price is down significantly or stagnant, shareholders are often more open to listening to a new group that comes in and proposes dramatic changes. After all, how much worse could it be vs. the current path?

That said, activist hedge funds still tend to get the best results in regions with a strong culture around “shareholder value,” such as the U.S. and the U.K.

They’re often less effective in places like Japan and continental Europe when everyone on the Board knows each other and won’t vote for change, no matter how poorly run the company is.

How Do Activist Hedge Funds Differ from Others?

Activist hedge funds tend to have the following qualities:

1) Long-Term Investment Horizon – It might take years to realize their changes, so their holding periods exceed most other hedge funds.

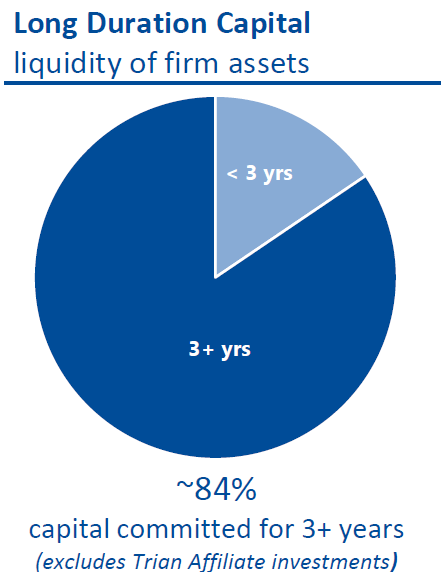

2) Longer Lockup Periods for Capital – This fact sheet from Trian Partners is useful for quantifying this one:

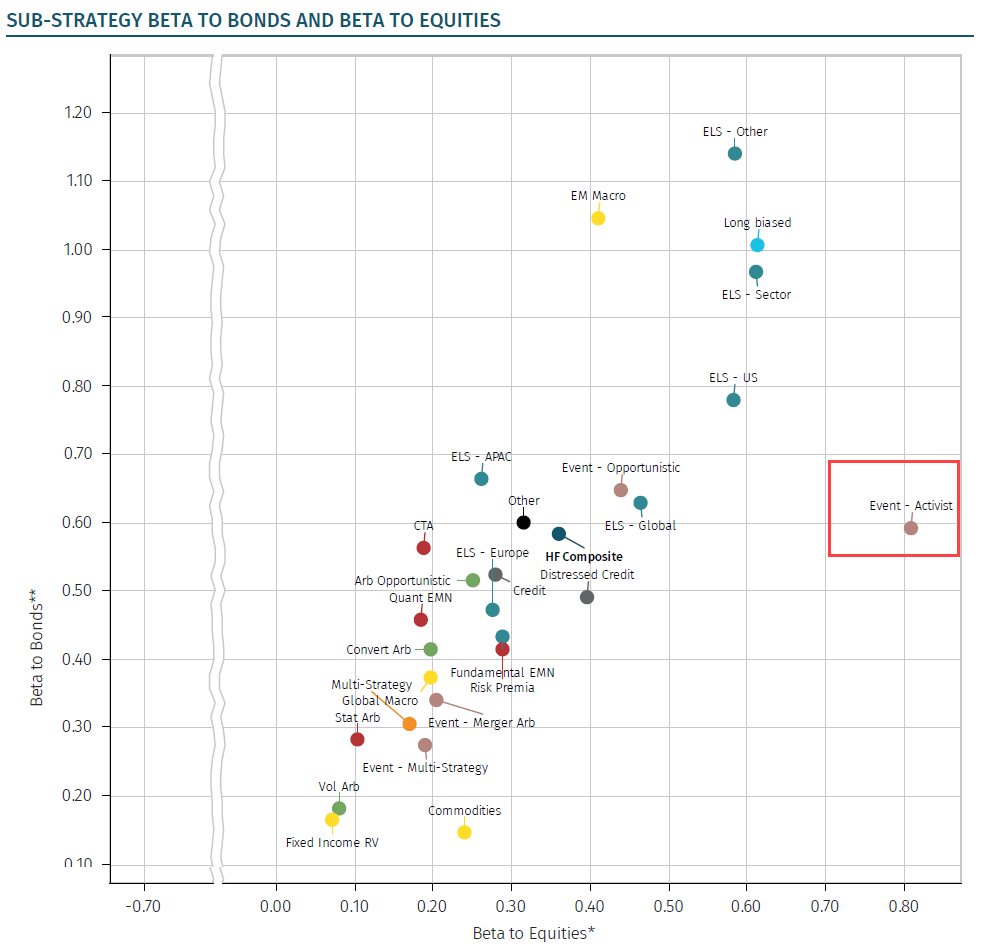

3) High Net Exposure and High Beta – Since most activist hedge funds target undervalued and misunderstood companies, they are effectively long equities most of the time. This point explains the following graph from Aurum’s Hedge Fund Industry Deep Dive (click the image for a larger version):

4) Normal Leverage Levels – Activist hedge funds have less-liquid positions and longer holding periods than global macro funds, so they tend to use less leverage; it’s on par with the average level for credit funds and a bit below the average for equity funds.

5) Concentrated Portfolios – It’s rare to find an activist hedge fund with 50 or 100 positions because each one requires substantial time and effort that goes far beyond normal “monitoring.” Cevian’s Strategy page has a great summary (significant minority ownership in 10-15 public companies at a time, 5-year holding periods, and €500 million – €1.5 billion per company).

Finally, activist funds tend to be larger (multi-billions of AUM or more) because it’s very difficult to buy substantial stakes in public companies with only $100 or $300 million of capital.

Activist funds with under $1 billion in AUM do exist, but they’re usually limited to small-cap companies.

Activist Investment Strategies

Activist hedge funds differ mostly based on their aggressiveness.

You can divide most strategies into these categories:

- ”Greenmailers” – This strategy involves purchasing enough shares of a firm to credibly threaten management with a hostile takeover. The only way the company can stop it, of course, is to buy back its shares at a premium. This strategy is a short-term, “quick flip” type approach, and Carl Icahn has used it in many of his older approaches (but less so recently).

- “Friendly Engagement” – These firms typically try to get on friendly terms with management and negotiate changes behind the scenes rather than launching high-profile, public campaigns to win over shareholders; time horizons are also longer. Example firms in this category include Cevian and ValueAct.

- “Aggressive Negotiations” – This is not quite the “Anakin Skywalker” strategy, but these firms use far more aggressive approaches and do not necessarily notify the Board before unveiling their stakes. Examples include Elliott and Starboard Value.

The Top Activist Hedge Funds

First, note that there aren’t that many “pure-play” activist hedge funds.

Some value-oriented funds occasionally launch public campaigns, but that doesn’t mean they’re “activists” in the traditional sense.

Some of the best-known activist hedge funds in the U.S. include Elliott Management, Third Point Partners, ValueAct Capital, Trian Partners, JANA Partners, and Starboard Value.

People will sometimes put firms like Pershing Square in this category due to some high-profile activist campaigns they’ve led.

And while Carl Icahn may be the highest-profile activist investor of all time, he hasn’t managed outside money since 2011, so Icahn Enterprises is not technically a hedge fund.

Other names include Ancora Advisors, Barington Capital, Corvex Management, Macellum Capital, Mudrick Capital, Sachem Head, Soroban Capital, and Engine No. 1 (effectively a BlackRock entity; it gained fame via its ExxonMobil campaign).

In Europe, the best-known activist fund is probably Cevian, which focuses on the Nordic and DACH (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland) regions.

Other well-known activist funds include TCI (“The Children’s Investment Fund Management”), Amber Capital, Bluebell Capital, Gatemore Capital, Petrus Advisers, PrimeStone Capital, Sparta Capital (Elliott spin-off), Teleios Capital, and Thélème Partners (TCI spin-off and former workplace of Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak).

How to Recruit into Activist Hedge Funds

The short answer is: “Work in investment banking, private equity, or both, and then use your deal experience to recruit for activist funds.”

Few activist funds hire candidates directly out of undergrad because you need substantial deal experience before you can add much value.

I did a quick/informal survey of those in my LinkedIn extended network with experience at activist hedge funds and found the following results for their previous backgrounds:

- Investment Banking: 43%

- Investment Banking & Private Equity: 17%

- Private Equity or Credit Investing: 9%

- Equity Research or Credit Research: 9%

- Directly Out of Undergrad: 9%

- Restructuring/Turnaround Consulting: 4%

- Management Consulting: 4%

- Other Hedge Fund/Asset Management Role: 4%

- Law: 4%

- Venture Capital/Growth Equity: 4%

Since there aren’t that many pure-play activist funds, recruiting tends to be very “random” – an individual fund does not necessarily hire new people every year or follow any schedule.

To maximize your chances, work at the best bank you can get into and then join a private equity mega-fund or an upper-middle-market fund.

In Europe, some funds prefer candidates with a consulting or combined consulting/banking background; Cevian is in this category.

The recruiting process can be quite intense because many activist funds run lean teams, and competition is fierce because of the perceived “prestige,” compensation, and sporadic hiring.

For example, Elliott is known for conducting multi-month recruiting cycles and giving candidates psychological profiles or IQ tests in addition to all the standard interview questions.

Interviews, Case Studies, and Stock Pitches

Case studies, modeling tests, and stock pitches are similar to those in the long/short equity or credit fund recruiting processes.

In other words, expect to complete a fundamental-based valuation (DCF and multiples) of a company and recommend investing based on the output in different cases.

The main differences are:

- Time Frames – You can assume longer time frames here, such as 2-3 years rather than the normal 6-12 months, because activist strategies often take years to pay off.

- Catalysts – Rather than relying on external “hard” or “soft” catalysts, you should make your own catalysts by suggesting the specific changes the company must make to increase its valuation.

- Target Companies – Finally, it can be much harder to craft your own stock pitches because you need to find a company that is undervalued/misunderstood due to specific management or operational issues that can be fixed – not just because the company’s core market is shrinking or because a recent product sold poorly.

This last point explains why these funds might assign you a company or situation rather than asking you to develop an idea independently.

Activist Hedge Fund Careers, Hours, and Compensation

Hedge fund compensation is linked to fund size, performance, and individual performance/contributions, so it’s impossible to say if the “average” activist hedge fund employee earns more or less than the average at other fund types.

I’ve seen some SumZero compensation reports from previous years that break out median compensation by strategy, but they’re not that useful due to big fluctuations from year to year (“activist” is in the mid-to-lower end of the range for compensation, if you’re curious, but I wouldn’t read much into it).

That said, it is fair to say the following about activist hedge funds:

- Promotion: It’s arguably easier for high-performing Analysts to win promotions to Portfolio Manager and eventually Partner because they tend to be involved with everything in the investment process. You’re less likely to be “siloed” than in a strategy like merger arbitrage.

- Hours: The hours are often more “variable” than other types of hedge funds because you could easily get involved in an active investment that starts consuming your attention 24/7 if, for example, the company announces plans for a spin-off, break-up, or sale of the entire company. It’s closer to the IB/PE cycle, where hours fluctuate significantly based on deal activity.

- Headcount: The hours also tend to be longer because many of these firms have extremely lean teams despite fairly high AUM. I don’t think anyone has data on the average AUM per Employee broken out by hedge fund strategy, but I would not be surprised to see higher-than-average figures for activist funds.

Exit Opportunities

Since you probably worked in investment banking, private equity, or both before moving into an activist hedge fund, you could also leave and return to one of them.

If you’ve somehow gotten into an activist fund without doing one of those first, it will be much harder to make this move.

Yes, you do work on “deals,” but it’s a far less comprehensive process, and you’re not responsible for executing all the steps (or even advising on them).

Your main goal is to persuade other shareholders, which means you spend more time on presentations and outreach than on reviewing the fine print on page 157 of the merger agreement.

Since activist investing overlaps with other strategies such as long/short equity, credit, and even merger arbitrage, you could potentially move into a fund or group in one of these areas.

Long-only asset management is also a possibility, but you’re probably not the best fit because of the active vs. passive nature of these two fields.

If you’re at a fund that also invests in debt, you could also potentially move into direct lending, mezzanine, or credit hedge funds.

Other deal-based roles such as corporate development, venture capital, or growth equity are theoretically possible but not that likely.

You work with very different companies in the latter two, and with CD, you use a very different mindset when acquiring companies that your firm plans to hold indefinitely.

So, these are likely exits only if you’ve worked in one of them before joining an activist fund.

Additional Resources

You can find dozens, if not hundreds, of activist hedge fund presentations and letters online, but there are surprisingly few good books about the sector.

Here are some recommendations by media type:

Books

- Dear Chairman: Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism

- Extreme Value Hedging: How Activist Hedge Fund Managers Are Taking on the World

- Activist Hedge Fund Transactions

- Barbarians in the Boardroom

Presentations, White Papers, and Investor Letters

- Elliott – Previous Letter and Materials

- Starboard Value – Presentations

- Trian Partners – White Papers and Presentations

- Petrus Advisers – Active Investments (Various Presentations and Offer Letters)

Specific Presentations by Activist Hedge Funds

Finally, a few useful presentations and letters include:

- Elliott – Crown Castle (Telecom Infrastructure)

- Elliott – GSK (Pharmaceuticals)

- Elliott – Healthcare Trust of America (Healthcare REIT)

- Elliott – Sampo (Insurance)

- Elliott – Suncor (Energy)

- Starboard – Darden Restaurants

- Starboard – Huntsman, Colfax, and Elanco

- Starboard – Willis Towers and Corteva

- Trian – Ferguson (Plumbing/Heating Products)

- Trian – Proctor & Gamble (Consumer)

- ValueAct – Seven & i Holdings (Conglomerate/Holding Company)

Activist Hedge Funds: Final Thoughts

In many ways, activist hedge funds are “more interesting” versions of long/short equity or credit funds.

They use similar valuation and research methodologies, but they make their own catalysts – or attempt to do so – and profit based on undervalued companies with untapped potential that need major changes to realize that potential.

This strategy makes the work more interesting, but it also comes with a downside: these funds tend to be highly correlated with the overall market, so it’s difficult to say how much of a “hedge” they provide.

The other major issue is that there aren’t that many pure-play activist funds, and the ones that still exist are becoming tamer or turning into private equity firms.

But depending on your career goals, that might be an advantage.

After all, if you can’t decide between private equity and hedge funds, there’s nothing better than joining an activist hedge fund that turns into a private equity firm.

Just make sure you don’t turn into a Twitter “activist” in the process.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

How likely is it to break into a fund like Elliott or Trian only after a few years of stint in IB( that too in Singapore/London), followed by an MBA in the US .

Can’t really say, as it is 100% dependent on your experience, networking, and ability to present good ideas in interviews. Hedge fund recruiting is more ability-driven and less prestige-driven than PE recruiting.

Are the Activist Hedge Funds more like the L/S single manager funds or they share more similar traits with PE. I know its quite relative question but what’s your thoughts?

As stated repeatedly in the article, they are a mix of both, and some have become more like PE firms over time.

Thanks Brian, really nice article as usually

Thanks!