Oil & Gas Investment Banking: The First Victim of the ESG Cult?

With the possible exception of FIG, oil & gas investment banking generates the highest number of panicked emails and questions.

Historically, these panicked questions were usually variations of:

“Will I get pigeonholed? I don’t want to be stuck in oil & gas forever. How do I move around? Help!”

That’s still a concern now, but the panicked questions have shifted to:

“Will ESG kill the energy star? Will oil & gas still exist in 5 or 10 years? Isn’t the entire world going to stop using fossil fuels immediately and switch to solar power for everything?”

I can understand these concerns, but they’re both overblown.

The first one about becoming pigeonholed is more valid, but it depends on your experience and how quickly you move around.

But before delving into the exit opportunities and the long-term outlook, let’s start with the fundamentals:

Oil & Gas Investment Banking Defined

Oil & Gas Investment Banking Definition: In oil & gas investment banking, professionals advise companies that search for, produce, store, transport, refine, and market energy on raising debt and equity and completing mergers and acquisitions.

In this article, we’ll assume that there are 5 major verticals within oil & gas:

- Exploration & Production (E&P or “Upstream”) – These companies explore and drill for oil and gas in different locations; once they find deposits, they produce the energy.

- Storage & Transportation (“Midstream”) – These firms transport oil and gas from the producers to the refiners via pipelines, ships, and other methods.

- Refining & Marketing (R&M or “Downstream”) – These firms turn crude oil and gas into usable products, such as gasoline for cars and jet fuel for planes.

- Integrated Oil & Gas – These companies do everything above and are diversified across geographies. Many are owned in whole or in part by governments (“national oil companies” or NOCs).

- Energy Services (“Oilfield Services” or OFS) – These firms “assist” the companies above, typically by renting out drilling equipment (rigs) or offering engineering/construction services. They do not own oil & gas deposits directly.

If you work in oil & gas investment banking, you’ll normally specialize in one of these verticals, which could be good or bad depending on market conditions and your long-term goals.

Different banks classify their oil & gas groups differently.

For example, Morgan Stanley has an “Energy” group that includes oil & gas, while Goldman Sachs and BofA both put it in “Natural Resources.”

Oil & gas may also be grouped with mining, power/utilities, or renewable energy, but these sectors are all quite different in practice.

Recruiting into Oil & Gas Investment Banking

Oil & gas is highly specialized, so you have a substantial advantage if you enter interviews with industry experience or technical knowledge (e.g., petroleum or geophysical engineering).

It’s not “required,” but it can act as a tiebreaker for 2-3 otherwise very similar candidates.

And regardless of your experience, you do need a demonstrated interest in the industry to have the best shot at getting in.

This could mean anything from an energy-related internship, club, or activity to additional classes you’ve taken or some type of family background.

It’s also worth noting that many banks have “coverage” oil & gas investment banking teams and separate “acquisition & divestiture” (A&D) teams.

The A&D teams focus on asset-level deals (e.g., buying or selling one specific oil field rather than an entire company), and they tend to hire people with technical backgrounds, such as reservoir engineers, to assess these assets.

So, if you have a technical background, you will have a much easier time getting into this industry if you target A&D teams rather than traditional IB coverage roles.

Other than that, banks look for the same qualities in candidates that they do anywhere else: a good university or business school, high grades, previous internships, and solid networking/preparation.

You do not need to be an “expert” in the technical details of oil & gas, but you should know the following topics:

- The different verticals and how the business models, drivers, and risk factors differ.

- Valuation, especially the NAV Model for Upstream companies and the slightly different metrics and multiples (keep reading).

- A recent energy deal (ideally one that the bank you’re interviewing with advised on).

- An understanding of MLPs (Master Limited Partnerships), including why many Midstream companies use this structure and why some have switched away from it.

- Different basins or production regions in your country. For example, if you’re interviewing in Houston, you should know about the Permian Basin, Eagle Ford Shale, and Barnett Shale and how they differ in production and expenses.

Finally, if you are interviewing for a role outside a major financial center – such as Calgary in Canada or Houston in the U.S. – it’s important to demonstrate some connections to that area.

These groups don’t want to hire bankers only to have them run off to Toronto or New York after 1-2 years.

What Does an Analyst or Associate in Oil & Gas Investment Banking Do?

Most people are drawn to the Upstream or E&P segment because they believe it has more real activity.

They’re partially correct; E&P has the most corporate-level M&A activity of all the verticals.

I searched for all oil & gas M&A and capital markets deals worth over $1 billion USD over the last 3 years (worldwide) and got the following results:

- Upstream: 88 (mostly corporate M&A with a mix of the other deal types)

- Midstream: 85 (mix of asset deals, M&A, debt, and even some private equity activity)

- Downstream: 31 (mix of everything, but no private equity activity)

- Integrated: 79 (almost all equity and debt offerings and a few asset deals)

- Services: 18 (mix of everything, with one notable PE deal)

If you want a more traditional investment banking experience, Upstream is your best bet – assuming that commodity prices have not crashed recently.

Integrated Oil & Gas can also work, but at the large banks, you’ll mostly advise huge corporations on prospective asset deals and the occasional financing.

The Downstream and Services segments tend to have lower deal activity, with many engagements taking the form of “continuous advice” to large companies.

Also, there are few “independent” Downstream companies in major markets like the U.S., meaning there are few sell-side M&A targets.

Many people overlook the Midstream vertical or assume it’s “boring” since storage and transportation companies operate more like utilities.

There is some truth to that, but:

- This vertical arguably has the greatest variety of deals.

- It’s less sensitive to commodity prices than the others.

- And it may be the best bet if you want to get into energy private equity since there is more PE activity, and Midstream buyouts are very specialized.

Oil & Gas Trends and Drivers

The most important drivers for the entire sector include:

- Commodity Prices – Higher oil and gas prices benefit most companies in the sector, but not always directly. They encourage companies to spend more to find new reserves and enhance their existing production; lower prices do the opposite. Higher prices also drive demand for supporting infrastructure, drilling, and engineering services.

- Oil and Gas Production, Reserves, and Capacity – Upstream companies are in a race against time to replace their reserves as they get depleted, but even if they find additional supplies, it usually takes 12-18 months for them to come online. This time lag means that disruptions to production capacity (wars, sanctions, natural disasters, etc.) can significantly impact prices.

- Finding and Development Costs – Also known as F&D Costs, these refer to the total expenses required to discover new reserves and turn them into usable commodities. These generally rise and fall with commodity prices, and higher F&D costs hurt E&P firms but help Energy Services firms by making their services more lucrative.

- Capital Expenditures – How much are companies spending to find new reserves and to maintain their existing production? CapEx spending has a ripple effect through the entire oil & gas market, as it affects demand for Energy Services and the volumes of resources processed by Midstream and Downstream firms.

- Interest Rates and Monetary Policy – Similar to utility companies, Midstream firms are often viewed as a “safe investment” alternative to bonds. Therefore, higher interest rates tend to make them less attractive; higher rates also make it more difficult for E&P and other firms to raise debt to finance their operations.

- Taxes, (Geo)Politics, and Regulations – Has the government increased taxes on oil and gas production or consumption? Did Russia invade another country? Have politicians imposed a “windfall tax” on energy companies? Even the mere hint that governments will encourage or discourage certain activities can change companies’ strategies.

Oil & Gas Overview by Vertical

I’ll walk through the market forces and drivers here and save the technical details for the section on accounting, valuation, and financial modeling.

Exploration & Production (E&P) or Upstream

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: ConocoPhillips, Canadian Natural Resources, EOG Resources, Pioneer Natural Resources, Devon Energy, PJSC Tatneft (Russia), Ovintiv, INPEX (Japan), Southwestern Energy, Chesapeake Energy, APA (Apache), EQT, Vår Energi (Norway), Aker BP (Norway), and Woodside Energy (Australia).

U.S. companies dominate this list because oil & gas production in countries such as Russia and China is the domain of state-owned Integrated Oil & Gas companies (see below).

Non-state-owned E&P companies have a simple-but-challenging task: expand production while maintaining or increasing their reserves.

Dedicated E&P firms are highly sensitive to commodity prices because they do not have other business segments to reduce the impact if prices fall.

Many smaller E&P companies use hedging instruments such as three-way collars and basis swaps to “lock in” prices, but most only hedge short-term prices.

Because the risk of searching for new energy sources and experimentally drilling is so high, many E&P firms set up joint ventures to distribute the risk.

And even when an E&P firm finds something, there’s significant uncertainty associated with oil and gas deposits.

Companies may classify these deposits as resources (more speculative) or reserves (confirmed by drilling, accurately measured, and economically recoverable using current technology).

There are also different reserve types, such as Proved (1P), Proved + Probable (2P), and Proved + Probable + Possible (3P).

Depending on the company, region, and technical details, its “reserves” might have to be discounted or risk-adjusted by some factor.

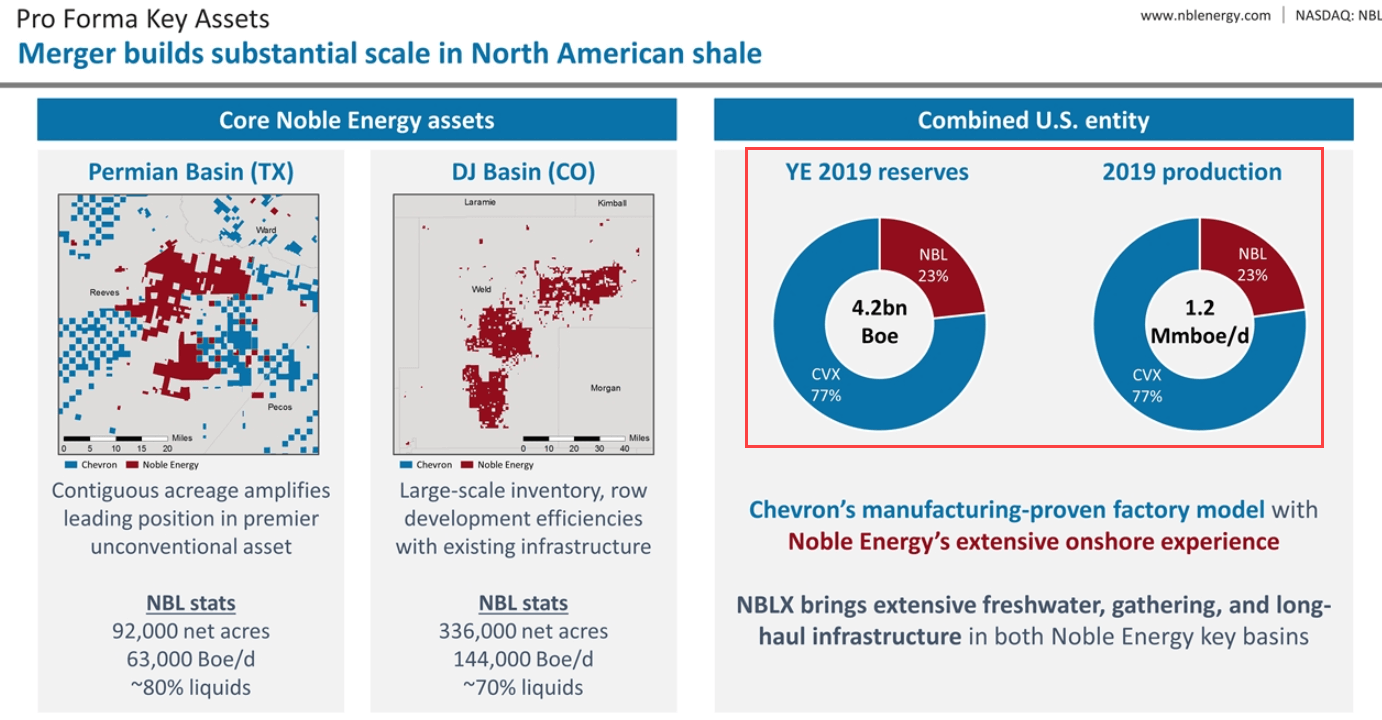

Almost every M&A deal in this vertical is motivated by reserve expansion, geographic diversification, and OpEx or CapEx reduction.

For a good example, check out the presentation for Chevron’s acquisition of Noble Energy:

“BOE” is “Barrel of Oil Equivalent,” a metric used to convert the energy produced by natural gas into the energy produced by oil to make a proper comparison.

The key problem for E&P companies is doing everything above while maintaining decent cash flow, which has historically been… a bit of a challenge.

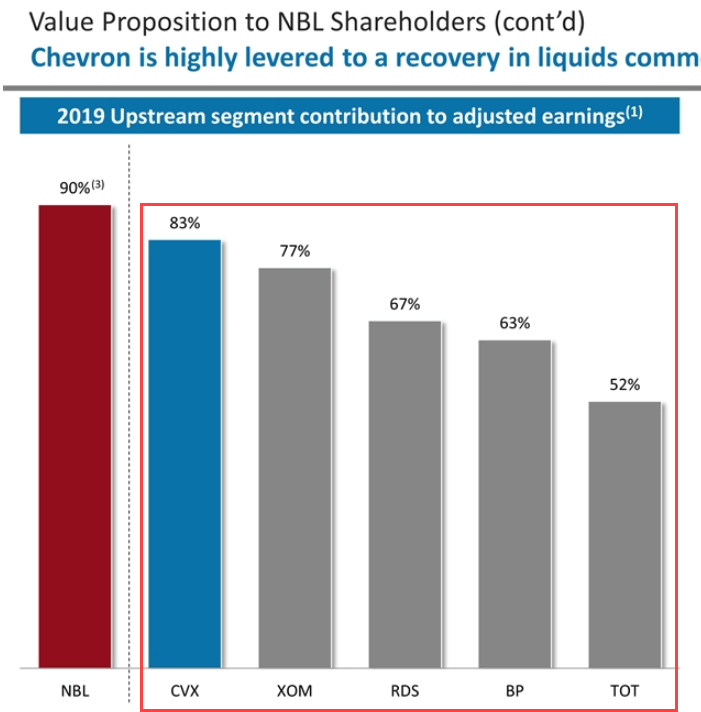

ONE FINAL NOTE: In addition to offering the highest risk and highest potential returns, E&P is also important because it tends to dominate the earnings of Integrated Oil & Gas companies:

In theory, companies like ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP are “diversified,” but if 60-80% of their earnings come from E&P, they’re not that diversified.

Storage & Transportation or Midstream

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Energy Transfer LP, Plains All American Pipeline LP, Enterprise Products Partners LP, Enbridge (Canada), Cheniere Energy, Ultrapar Participações (Brazil), Targa Resources, ONEOK, Kinder Morgan, Global Partners LP, Transneft (Russia), DCP Midstream, Petronet LNG (India), and Pembina Pipeline (Canada).

Outside the U.S. and Canada, most storage and transportation assets are provided by the Integrated companies, which explains this list.

Midstream companies act as the “middlemen” between the producers, distributors, and end users.

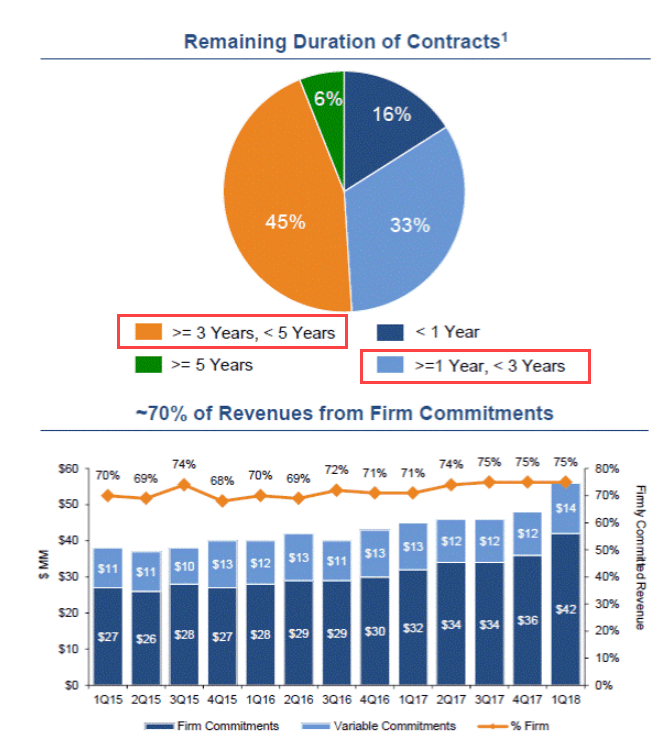

This vertical is less affected by commodity prices than the others because revenue is based on fees charged * volume transported – and the fees are often based on long-term contracts, as shown in this Evercore presentation to TransMontaigne Partners:

Therefore, if these companies want to grow substantially, they must spend to build, acquire, or expand their pipelines, ships, or storage terminals.

But it’s tricky to do this because most Midstream companies in the U.S. are structured as Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs), which are pass-through entities that do not pay corporate income taxes and distribute a high percentage of their available cash flows (e.g., 80-90%).

So, MLPs do not have high cash balances, and they rely on raising outside capital (mostly debt), similar to real estate investment trusts (REITs).

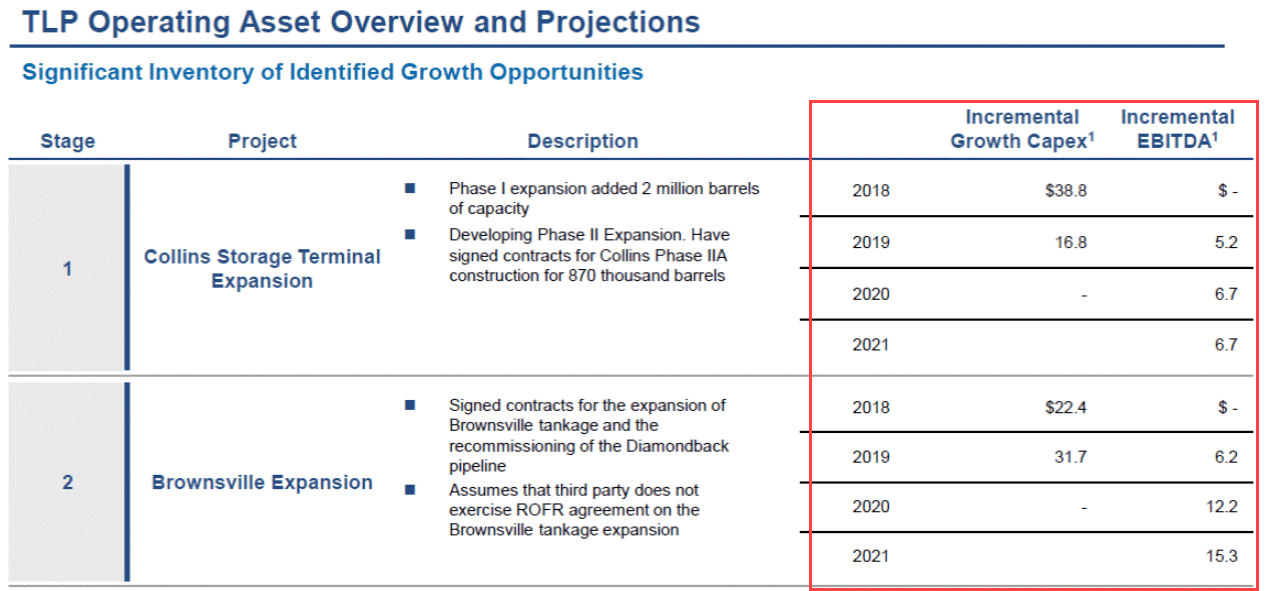

If Midstream companies want to grow beyond the fee increases written into their contracts and possible volume growth, they need to spend on Growth CapEx and estimate the incremental EBITDA from that spending:

Further adding to the complexity is the GP (General Partner) / LP (Limited Partner) structure used at most MLPs.

The GP is normally a larger energy company that controls the MLP management and operations and owns ~2% of the MLP’s “units.”

The Limited Partners own the remaining ~98% of the partnership but have a limited role in its operations and management, similar to the LPs in private equity.

Complications arise because the dividend payouts do not necessarily follow this 2% / 98% split; there’s usually a set of “tiers” with performance incentives, and the split changes in each tier, similar to the real estate waterfall model.

Many Midstream companies have been consolidating into C-corporations to simplify their structures and reduce potential unitholder conflicts (and because corporate tax rates in the U.S. have declined).

Refining & Marketing or Downstream

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Marathon Petroleum, Valero Energy, Phillips 66, ENEOS (Japan), Idemitsu Kosan (Japan), Bharat Petroleum (India), Hindustan Petroleum (India), World Fuel Services, Sunoco, SK Innovation (South Korea), Raízen (Brazil), PBF Energy, and S-OIL (South Korea).

This list is more geographically diverse because not every country has strong oil and gas production, but they all need distribution.

Downstream tends to be the least profitable segment for Integrated Oil & Gas companies because the margins for refining and selling petroleum-based products are usually slim.

The main drivers are each company’s refining capacity and refining margins.

In other words, how many barrels of oil per day can it turn into useful products (gasoline, diesel, heating oil, propane, jet fuel, etc.), and how much can it charge for those products above the price of the crude oil?

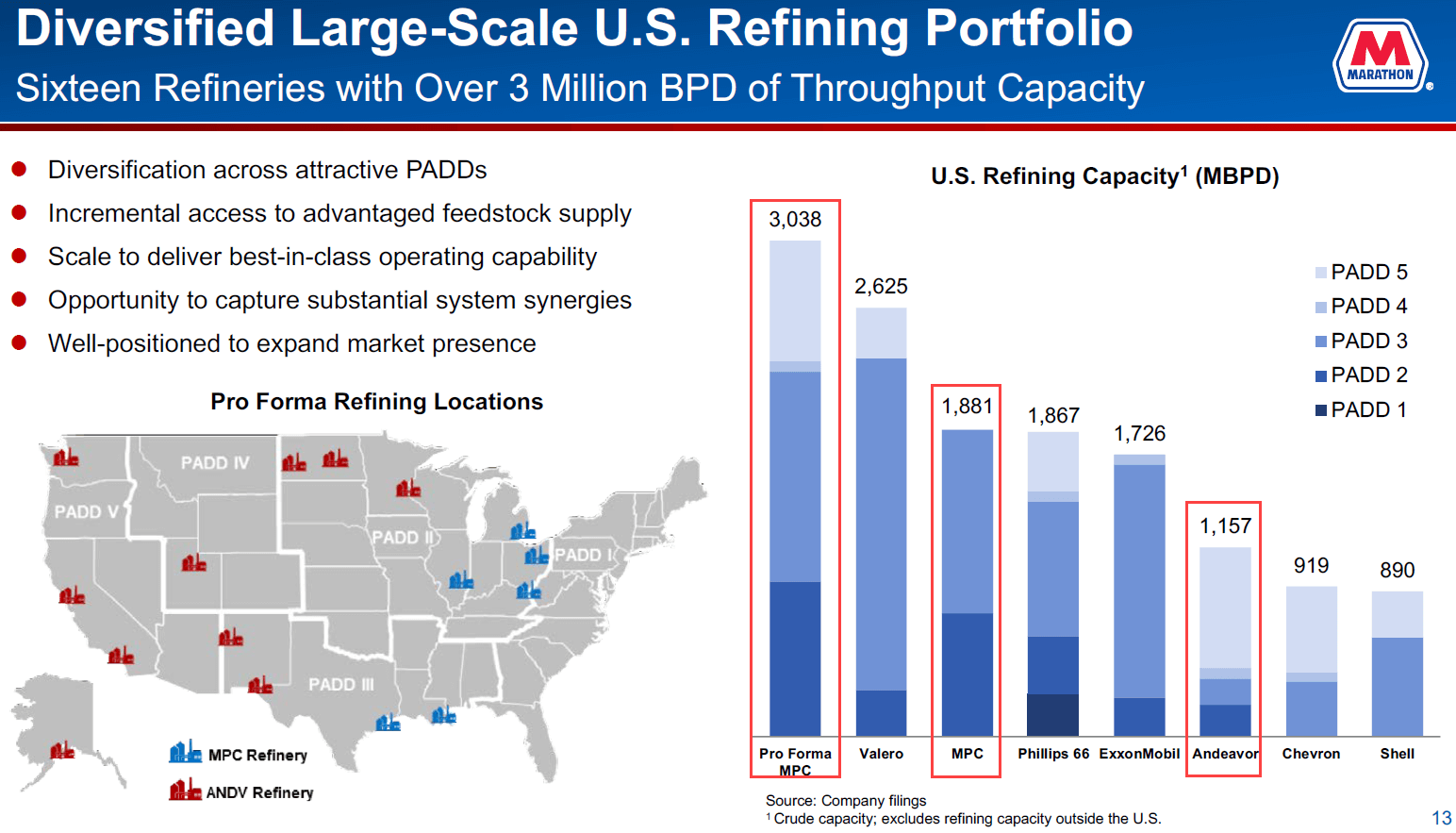

Almost every M&A deal in this sector is about improving refining capacity or margins or diversifying the company’s suppliers and geographies, as seen in the Marathon / Andeavor deal presentation below:

If Downstream companies want to grow, they have several options:

- Build new refineries – But this is increasingly difficult due to politicians and the ESG crowd; the last brand-new refinery in the U.S. was built in 1976 (!).

- Expand or enhance existing refineries – This one explains how refining capacity grew in the U.S. for several decades after 1976, despite no new refineries.

- Acquire new refineries or retail locations – Companies can expand existing refineries only so much, so M&A has become a key growth strategy.

- Hope for higher refining margins or volume – But most refineries already run at 90%+ of their capacity, so there’s limited room for volume growth.

The most interesting part of this vertical is that higher commodity prices often hurt Downstream companies.

That’s because Downstream firms purchase crude oil from E&P companies, so higher commodity prices translate directly into higher expenses.

For this reason, Integrated Oil & Gas firms have a “natural hedge” when commodity prices increase or decrease, as their Downstream results may offset (some of) their Upstream results.

One Final Note: Some Downstream companies report blowout earnings in periods of high oil prices, but it’s not because of the high oil prices.

Instead, it’s usually because there’s constrained refining capacity, which allows the refining margin to increase, more than compensating for higher crude oil prices.

Integrated Oil & Gas

Representative Large Companies (Public or State-Owned): Saudi Aramco, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), ExxonMobil, Shell (U.K.), TotalEnergies (France), Chevron, BP (U.K.), Gazprom (Russia), Equinor (Norway), PJSC LUKOIL (Russia), Eni (Italy), Rosneft (Russia), Petrobras (Brazil), PTT (Thailand), Repsol (Spain), and Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (India).

Finally, we arrive at the most geographically diverse list of companies.

I had to drop the “large-cap public” part because the world’s biggest oil and gas producers are state-owned or state-backed.

For example, Saudi Aramco is technically a “public company,” but it’s 98% owned by Saudi Arabia.

These companies are like combinations of the Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream verticals – but the Upstream results still tend to dominate earnings and cash flow.

Many of these companies even operate in other industries, such as chemicals and basic materials, so the Sum of the Parts (SOTP) Valuation is critical when analyzing them.

The most important point here is that the incentives for state-owned/backed companies are quite different.

A publicly traded oil & gas corporation owned by a broad set of shareholders in the U.S. has every incentive to increase its production while maintaining decent cash flow.

But state-owned companies do not necessarily want to do this because their goal is to support an entire country and enable certain geopolitical and military goals (e.g., Russia).

So, if they’ve determined that lower production and higher prices support these goals, they will cut production to make it happen (see: OPEC).

Finally, these companies are so big and geopolitically sensitive that significant corporate-level M&A deals are rare.

Instead, expect many asset deals, financings, and smaller buy-side M&A deals.

Energy Services

Representative Large-Cap Public Companies: Schlumberger, Baker Hughes, Halliburton, China Petroleum Engineering, Sinopec Oilfield Service Corporation, Tenaris (Luxembourg), Saipem (Italy), Technip Energies (France), Worley (Australia), John Wood Group (U.K.), TechnipFMC (U.K.), CNOOC Energy Technology & Services (China), PAO TMK (Russia), and NOV.

Energy Services companies depend on the underlying demand from the E&P and Integrated companies that use their drilling, equipment, and other services to find new reserves and produce energy.

The two broad categories are oil & gas drilling and energy equipment & services.

Drilling firms are tied directly to the E&P segment because they own the rigs that E&P firms rent to explore for and produce oil and gas deposits.

Equipment & services firms provide “everything except the rigs,” such as the parts needed to maintain existing wells, transportation services, and even construction for the energy infrastructure.

Key drivers include Upstream CapEx, worldwide rig counts, dayrates, and rig utilization.

Drilling firms’ profits depend on factors such as supply and demand – the # of rigs operating worldwide vs. the # that E&P companies could potentially rent – and the average daily rates they can charge for the usage.

Also, there are different types of rigs, with some firms focusing on offshore or deepwater regions and others focusing on conventional or unconventional (shale and oil sand) resources.

The entire Energy Services vertical is like a “high Beta” play on oil and gas prices.

When prices surge, this segment benefits even more than E&P firms, and when prices fall, this segment takes a beating because rig, equipment, and construction demand plummets.

Oil & Gas Accounting, Valuation, and Financial Modeling

The technical side of oil & gas is quite specialized, but I would argue that it’s less different than something like FIG (especially banks and insurance firms).

The main differences are:

- Lingo and Terminology – Particularly in the E&P vertical, a lot of jargon is used to describe the process of exploring, drilling, and operating wells.

- Metrics and Multiples – The metrics and valuation multiples also differ because of accounting differences and the importance of a company’s reserves and production.

- New or Tweaked Valuation Methodologies – The obvious one here is the NAV (Net Asset Value) Model in the E&P segment, but there are a few differences in the others.

E&P / Upstream Differences

At a high level, when analyzing and valuing E&P companies, you do the following:

- Split the company into “existing production” and “undeveloped regions.”

- Assume that the existing production declines over time until these reserves are no longer economically feasible.

- In the undeveloped regions, assume the company drills X number of new wells per year until its current inventory is exhausted (this will be based on factors like the average well spacing in each area).

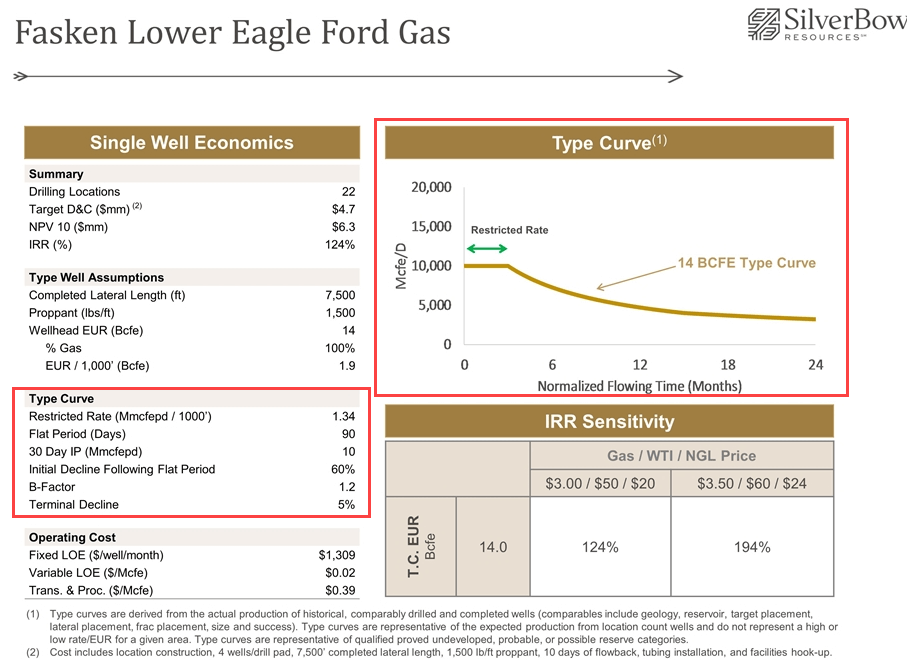

- Assume that each new well starts producing at its “IP Rate” (Initial Production Rate) and declines over time until total cumulative production reaches the average EUR, or Estimated Ultimate Recovery, for wells in the region.

- Build in scenarios for commodity prices, such as high/mid/low for oil, gas, and liquefied natural gas (LNG), and use these to forecast revenue based on production volume * average commodity price.

- CapEx and OpEx differ based on the well type and region, with most CapEx linked to “Drilling & Completion” (D&C) Costs and OpEx consisting of items like Production Taxes, Lease Operating Expenses (LOE), and other G&A.

- Aggregate the cash flows from all the wells in all the regions to create a cash flow roll-up. Cash Taxes may be complicated because of rules around deductions for different types of depreciation (intangible vs. tangible drilling costs) and depletion.

Other important concepts include working interests and royalties.

“Working interests” are agreements to split both revenue and expenses with another company to reduce the risk of new exploration and production, while “royalties” are percentages of revenue owed to the landowners.

Both need to be factored in to properly calculate revenue, expenses, and cash flow.

Then there are type curves, which are mathematical models used to predict the decline rate of wells based on curve fitting and various inputs:

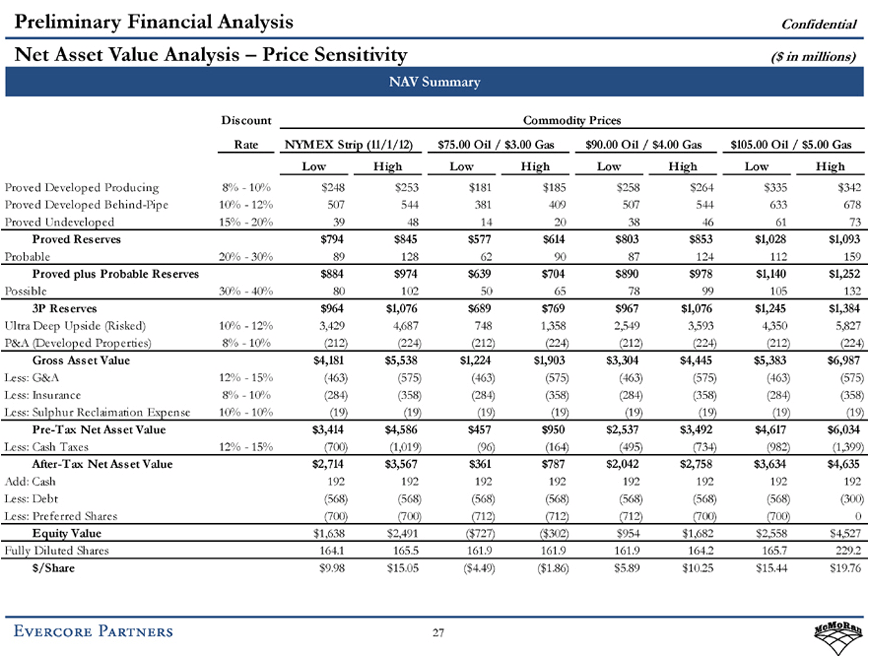

The NAV Model commonly used for E&P companies extends directly from the projection methodology above.

Essentially, the NAV Model is a super-long-term DCF without a Terminal Value.

The Terminal Value doesn’t make sense in this vertical because oil and gas resources are finite; you can’t assume that a company will keep producing “forever.”

So, you follow the steps above, project the company’s cash flows over several decades, and discount everything to Present Value.

The NAV Model output is split into different regions and reserve types and sensitized based on expected commodity prices, as in this E&P valuation presentation from Evercore:

Finally, a few common metrics and multiples for E&P companies include:

- EBITDAX and TEV / EBITDAX: EBITDAX is like EBITDA, but it also adds back the “Exploration” expense because under U.S. GAAP, some companies capitalize portions of their Exploration, and others expense it. EBITDAX normalizes for these accounting differences.

- TEV / Daily Production and TEV / Proved Reserves: These remove commodity prices from the picture and value E&P companies based on how much they are producing in Mmcfe (Million Cubic Feet Equivalent of Natural Gas Equivalent) or BOE (Barrels of Oil Equivalent) and how much they still have in the ground.

- Reserve Life Ratio and Reserve Replacement Ratio: The Reserve Life Ratio equals the company’s Proved Reserves / Annual Production, and the Reserve Replacement Ratio is the Annual Increase in Reserves vs. the Annual Reserve Depletion from Production. Both measure how effectively an E&P company is discovering or acquiring new hydrocarbons.

Midstream Differences

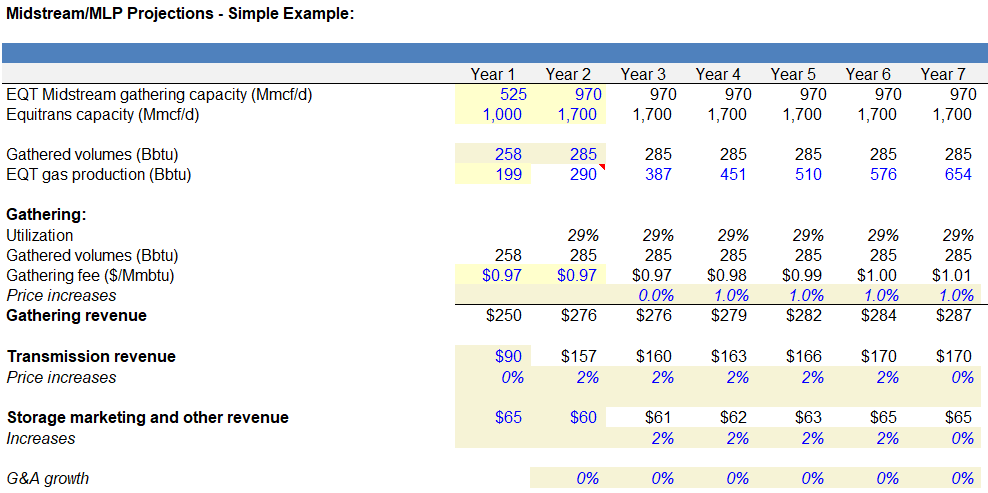

Projecting Midstream companies is not difficult: assume a gathering capacity, utilization rate, and average gathering fee (usually in a unit like $ per million British thermal units) and base revenue on these drivers:

Expenses can be linked to the revenue, gathering capacity, or volumes processed, and CapEx is split into maintenance and growth (to expand or build new facilities).

The tricky part is understanding the MLP structure and the tax, dividend, and capital structure differences that it creates.

You can still use EBITDA, TEV / EBITDA, and the DCF Model to value Midstream companies, but you’ll also see some additional metrics:

- Yields: These are important because MLPs have high and stable Dividend Yields, so they can be compared to other “fixed income-like” equities such as utilities and REITs.

- Cash Available for Distribution (CAFD): You can also turn this into an Equity Value-based valuation multiple (P / CAFD) since this cash is available only for the GPs and LPs in the MLP (i.e., it’s after the interest expense and preferred dividend deductions).

- Discounted Distribution Analysis: This one is similar to the Dividend Discount Model, but it includes the impact of different “tiers” for the GPs and LPs and differentiates between the cash flow available and the cash flow distributed.

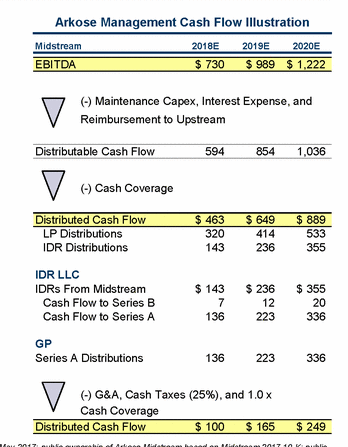

This Goldman Sachs presentation to Arkose has a good summary calculation:

Other Verticals

Some of the metrics and drivers differ in the other verticals, but the accounting and valuation methodologies are all fairly standard: EBITDA, TEV / EBITDA, the Unlevered DCF, and so on.

I’ll link to bank presentations and Fairness Opinions for the other segments below, but they’re not worth expanding on here.

Example Valuations, Pitch Books, Fairness Opinions, and Investor Presentations

Many companies operate across multiple verticals, so I haven’t done a strict screen for pure-play companies in each vertical.

Also, I’m not listing Integrated Oil & Gas companies as a separate category because they’re a combination of the other verticals.

E&P (Upstream)

- ConocoPhillips / Concho Resources – Corporate Acquisition (CS, JPM, and GS)

- Deal Presentation

- Fairness Opinions – CS | GS | JPM

- Woodside / BHP – Australian Company’s Acquisition of BHP’s Petroleum Business (Barclays, JPM, GS, UBS, MS, Gresham, Rothschild, and KPMG)

- Devon Energy / WPX Energy – Merger of Equals (JPM and Citi)

- Deal Presentation

- Fairness Opinions – JPM | Citi

- EQT / Rice Energy – This was an “activist campaign” run from within the company in which the Rice brothers gained control of the Board after EQT acquired Rice

Midstream

- Antero Midstream Corporation / Antero Midstream Partners – “Simplification” deal in which the company turned into a C-corporation (GS, MS, TPH, JPM, and Baird)

- Tallgrass Energy / Tallgrass Energy Partners – Financing discussion for a “buy-in” deal, followed by a Blackstone-led leveraged buyout (Evercore, Barclays, and Citi)

- Equitrans Midstream / EQM Midstream Partners – Another MLP “buy-in” deal (Evercore, Guggenheim, and Citi)

- Deal Presentation

- Guggenheim and GS – Preliminary Analysis and Presentation

- Fairness Opinions – Guggenheim | Evercore

Downstream

- Marathon / Andeavor (Tesoro) – Corporate Acquisition (Citi, GS, and Barclays)

- Deal Presentation

- Fairness Opinions – Barclays | GS

- Idemitsu Kosan / Showa Shell Sekiyu – Corporate Merger in Japan (Daiwa, GS, JPM, Mitsubishi UFJ, Lazard, and Mizuho)

- Hartree Partners / Sprague Resources – Acquisition of the remaining 25.5% stake; Sprague is a combined Downstream / Midstream company (Evercore and Jefferies)

Energy Services

- Enerflex / Exterran – U.S./Canada Cross-Border Deal (RBC, Scotia, TD, and Wells Fargo)

- Deal Presentation

- Fairness Opinion – Wells Fargo (search for “Opinion of the Financial Advisor to Exterran – Opinion of Wells Fargo Securities, LLC”)

- Parker Drilling – Bankruptcy/Restructuring Deal (Houlihan Lokey)

- Ensco / Rowan – Merger of Offshore Drilling Companies (GS, Citi, HSBC, and MS)

Oil & Gas Investment Banking League Tables: The Top Firms

You can get a sense of the top banks in this sector by looking at the lists above, but in short: banks with large Balance Sheets tend to do well.

Oil & gas is very dependent on debt and equity financing, so the bulge brackets have a distinct advantage over smaller/independent firms here.

This is why you repeatedly see firms like JPM, Citi, and Barclays in the deal lists above.

Less Balance Sheet-centric firms such as GS and MS also perform well due to brand and relationships.

In other regions, such as Australia, you’ll find firms like UBS advising on high-profile deals because UBS still has regional strength there.

The same applies to Canadian deals and Big 5 Canadian banks like RBC, Scotia, TD, and BMO.

Evercore is the clear standout among the elite boutiques, and Jefferies is easily the strongest middle market bank and one of the overall strongest for asset-level deals (A&D).

Moelis advises on a smaller number of more complex deals, so you won’t necessarily see them in the league tables, despite a solid team.

Other names worth noting include Intrepid, Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH), and Houlihan Lokey for restructuring deals.

Simmons & Co. was another strong independent in this sector, but it was acquired by Piper Sandler.

Oil & Gas Investment Banking Exit Opportunities

The short answer here is that exit opportunities are good if you stay within oil & gas and not so good otherwise.

Even if you work in a more “generalist” vertical, such as oilfield services, recruiters do not take the time to understand your experience, so they’ll always funnel you into O&G roles.

Another issue is that few private equity firms focus on oil & gas, partially due to commodity price volatility.

There’s a decent amount of hedge fund activity in the sector, especially since many smaller E&P names are poorly covered, but it’s not enough to compensate for the lack of PE firms.

My general advice here is:

- If you want to stay in oil & gas, try to work on Upstream or Midstream deals; Midstream is arguably the best for PE roles because Midstream PE funds are very, very specialized, and there’s more activity from financial sponsors.

- If you want to move into a generalist role, leave as soon as possible and be prepared to move “down-market” if necessary (e.g., bulge bracket to lower-middle-market PE fund). Another option might be to transfer into a generalist IB industry group

If you want to stay in energy, pretty much anything is open to you: private equity, hedge funds, corporate development, corporate finance, etc.

The main point is that you must decide quickly whether you want to stay or switch sectors.

The Future: Will ESG Kill the Oil & Gas Industry?

You’ve probably seen all the hype about ESG, the “Energy Transition,” “Net Zero” by 2050, and so on.

I am very skeptical of “ESG,” and while I don’t want to delve into my specific problems with it here, Damodaran and Lyn Alden both have good summaries.

That said, you might wonder if oil & gas is still a good sector since it seems like many people want to destroy it.

The short answer is that, if anything, this ESG pressure will increase deal activity in the short term as large companies seek to divest their assets to smaller operators.

And even in the long term – say, several decades into the future – oil and gas will never “go away” for several key reasons:

- Lack of Proper Substitutes – For example, in the U.S., 1/3 of oil is used for non-transportation purposes and cannot be easily electrified. Natural gas is even harder to replace because the majority goes to sources other than electricity generation.

- Lack of Grid-Scale Storage for Renewables – As long as solar and wind are “intermittent,” they cannot replace fuel sources like coal, nuclear, and natural gas for electricity generation. Technology could change this, but not anytime soon.

- China and India Don’t Care – Other emerging markets also fall into this category. Yes, maybe the U.S., Europe, and Japan will attempt to switch off oil and gas, but these places have small and declining populations vs. the rest of the world.

- Fossil Fuels Are Required to Build Renewables – To dig up and process the key metals used in solar panels and EV batteries, you need… oh, that’s right, fossil fuels. Google it and look up the processing steps if you don’t believe me.

If you go 500 or 1,000 years into the future, we’ll probably be on different energy sources by then, but that’s not relevant to your career planning.

The bigger issue with O&G is that the sector is always highly cyclical, and the ESG pressures further increase that cyclicality.

For Further Reading and Learning

Yes, we used to offer an Oil & Gas Modeling course but have discontinued it.

I like the sector, but the course needed a complete revamp (~2,000 hours of work), and it wasn’t selling enough to justify it.

We may reintroduce it in the future if I can find an easier/faster way of creating a new version.

In terms of other resources:

- News: Oil & Gas Journal, Upstream Online, World Oil, Rigzone, Oil & Gas Today (Australia); sites like the WSJ and FT also have dedicated energy sections.

- Industry Research: Search for the Deutsche Bank or Credit Suisse “Energy Primers” for good starting points (I don’t like to link to banks’ internal, non-public materials here); also, check out the coverage from Big 4 firms like Deloitte and PwC. The Alerian MLP Primer is quite good as well.

- Books: I’ve never found great books on valuation and financial modeling in this sector, but you can find a few references on Amazon. I’ve heard that Energy Trading & Investing is a useful overview, and the Fisher volume is also a decent introduction.

Final Thoughts on Oil & Gas Investment Banking

If you specialize in oil & gas and stick with it, you can earn and save a lot of money while living in low-cost locations like Houston.

I would also argue that the technical and deal analysis, at least for Upstream and Midstream companies, is more rigorous and interesting than the typical process in a generalist group.

More than ESG or the “Energy Transition” or “Net Zero,” the biggest downsides to oil & gas investment banking are the cyclicality and the specialization.

If you don’t like it, get out early – even if it means trading down to a smaller firm.

The cyclicality matters because you might get poor deal experience for several years and worse exit opportunities for reasons beyond your control.

It won’t matter if you stay in the industry for 10-15 years, but if you’re in it for 2-3 years, it could hurt you.

And yes, if we look 100-200+ years into the future, the oil & gas industry might be completely different or not exist at all.

But by then, we’ll all be dead, cryogenically frozen, or implanted in robots.

So, I’m not sure it matters as long as the cryonics and robots are powered by solar panels.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Excellent article. Names of other energy ideas you can invest in besides individual companies.

Thank you.