Structured Finance: The Most Interesting Deals at a Bank, or the Pathway to the Pigeonhole?

Structured Finance might be the rare sector of finance that has become less controversial over time.

Right after the 2008 financial crisis, everyone wanted to blame the big banks for everything.

And many focused their wrath on the securitization practices that gave us toxic subprime mortgages and a housing market crash.

More than a decade after that crisis, though, people have moved onto blaming other targets, such as Big Tech, Big Pharma, and private equity.

So, it seemed like a good time to revisit Structured Finance and break down the industry, from over-collateralization to exit opportunities:

What is Structured Finance?

Structured Finance Definition: In Structured Finance, banks pool together loans backed by cash flow-producing assets into securities and sell “tranches” of these securities into the capital markets; these securities use tools like credit enhancements to make each tranche riskier or less risky than the “average loan” in the pool.

The most common Structured Finance products are mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and asset-backed securities (ABS) for auto loans, home equity loans, student loans, and credit card receivables.

Other examples include collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), synthetic financial instruments, and collateralized bond obligations (CBOs).

Companies (“originators”) raise capital via structured products because they can often do so at a lower overall cost than if they used traditional financing options, such as a corporate bond issued directly by the company.

Lenders in areas such as mortgages and auto loans like structured products because they provide liquidity and capital and make it easier to issue additional loans in the future.

Finally, the investors who buy structured products like them because they can earn higher yields on assets that would normally be too risky to invest in directly – but which now carry a reduced risk if the products are constructed properly.

Structured Finance vs. Securitization

The terms “Structured Finance” and “Securitization” are often used interchangeably, but there are some differences.

The main one is that “Structured Finance” is a broader term that may refer to any transaction that uses special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) to add “special features” to loans.

“Securitization” refers to the specific process of pooling together loans, turning them into a security, and selling tranches or “slices” of that security.

So, Project Finance loans issued to fund infrastructure projects such as power plants and toll roads could be considered “Structured Finance” transactions even if they are not securitized.

In this article, we’re not going to distinguish between Structured Finance and Securitization because the everyday usage is so similar.

Structured Finance at the Large Banks

Similar to Debt Capital Markets (DCM), there is a lot of overlap with Sales & Trading, and some banks put their Structured Finance (SF) teams within S&T rather than IB.

Within the SF team, there are bankers, traders, structurers, and salespeople, and each one performs a different role.

The bankers are responsible for origination, i.e., pitching new offerings to clients and potential clients and coming up with ideas for new securities that investors might like.

The salespeople sell these securities and give pricing and deal input, and the traders support these securities in the capital markets once they’ve been issued.

The structurers do something closer to “real math” and build the statistical models to predict the probabilities of borrowers defaulting, prepaying their loans, and so on – and these inputs feed directly into bankers’ cash flow models for the securities.

Structured Finance Products: A Simple Example

Before proceeding, we need to explain the “special features” of these structured products that alter their risk/return profiles.

Let’s say that you have two loans: Loan A for $1 and Loan B for $1.

Each loan has a default probability of 10%, and their default rates are uncorrelated.

If either loan defaults, it pays $0; if it does not default, it pays $1.

You pool together the two loans for $2 total and then issue two $1 tranches for a special purpose vehicle (SPV) representing this pool of loans.

The $1 Junior Tranche is the first to absorb losses, so if Loan A or Loan B defaults, this Junior Tranche pays $0.

This Junior Tranche pays $1 only if neither loan defaults.

On the other hand, the Senior Tranche pays $1 if Loan A or Loan B defaults or if neither one defaults.

It pays $0 only if both loans default – in that case, the Junior Tranche absorbs the first $1 loss, and then the Senior Tranche absorbs the next $1 loss.

Therefore, the Senior Tranche has a default probability of 10% * 10% = 1%, assuming that the default probabilities of Loan A and Loan B are uncorrelated.

But the Junior Tranche has a default probability of 1 – (1 – 10%) * (1 – 10%) = 19%.

The Junior Tranche investors lose everything if Loan A defaults, if Loan B defaults, or if both loans default.

In exchange for this higher risk, investors in the Junior Tranche will also earn a higher yield, and the Junior Tranche will receive a lower credit rating.

This is an example of subordination, and it’s a feature of almost every structured product: the issuer pools the loans and splits them into tranches with different risk/return profiles.

Two points should be clear from this simple example:

- Certain tranches will be less risky than the “average” underlying loan – if the pool is large enough and the tranches are set up properly. The Senior Tranche here has a default probability of 1% vs. the 10% default probability for Loans A and B separately.

- But this “trick” is heavily dependent on the default probability correlation across the pool of loans. As default probabilities become more correlated, it becomes more difficult to create low-risk and high-risk tranches.

Just ask anyone who invested in subprime mortgage-backed securities in 2006 about that last one…

Structured Products: More Complex Features

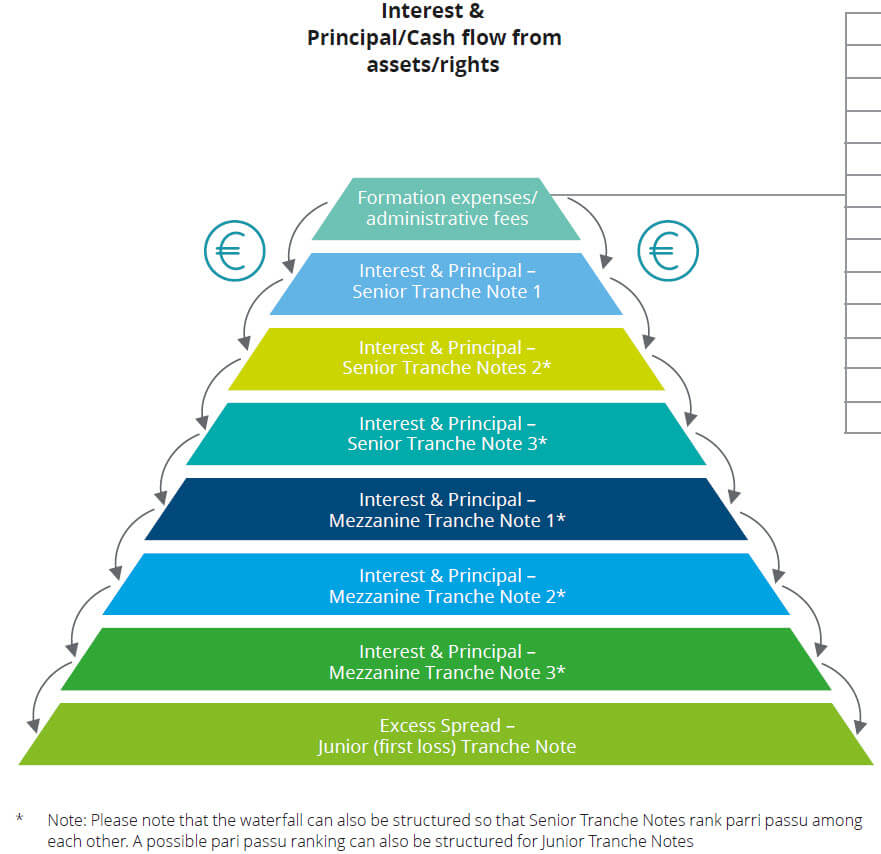

This example of subordination is the best-known feature of structured products, and it creates “cash flow waterfalls” like the one below (source: Deloitte):

But if you want to take the red pill and stay in wonderland, you’ll see just how deep the structured rabbit hole goes.

Credit enhancements that boost the credit ratings of structured products could be internal or external.

The subordination described above is an example of an internal credit enhancement, and so is over-collateralization.

In this process, an issuer might pool together $500 million of loans but then issue only $480 million of securities.

The value of the pledged collateral is greater than the value of the securities, so there’s an extra “cushion” before the most junior tranche starts taking losses, and that cushion boosts the credit ratings of all the tranches.

Then there are reserve/spread funds, which the originator usually funds at the start of a securitization.

The originator pays into an account and invests these funds in liquid, investment-grade securities, and if there’s a default in the loan pool, the unpaid principal is deducted from this reserve account and paid to the investors.

Effectively, it’s another “cushion,” but it results from the originator paying extra.

Excess spread is another credit enhancement, and it represents the difference between the interest and fees paid to the structured security’s buyers and the interest received by the security’s issuer.

This excess amount may cover losses as they are incurred; if no losses are incurred, it might be placed in a reserve account to cover future losses.

And then there’s bankruptcy remoteness, which means that if the issuing company defaults or goes bankrupt, the bankruptcy court cannot touch the collateral backing the structured notes or use them to repay another party.

External credit enhancements are less common, but examples include letters of credit in which a bank or other financial institution is paid to cover losses up to a certain amount.

This one is “external” because a separate financial institution, rather than the issuer or originator, provides the cushion via insurance.

And then there are surety bonds, also called performance bonds, which are actual insurance policies that reimburse the issuer for losses on the collateral pool.

These credit enhancements help structured products receive higher credit ratings and, therefore, lower interest rates.

Since many issuers of structured securities have below-investment-grade credit ratings, they have a greater need for credit enhancements than, say, a blue-chip Fortune 500 company.

And while it’s common to securitize auto loans, credit card receivables, and student loans, you could securitize almost any future income stream.

More esoteric asset classes include alarm contracts, movie studios’ film franchise revenues, aircraft fleet leases, restaurant franchise fees, and even future music album sales.

All it takes is the perception of stable and predictable cash flows, and bankers can turn the cash flow stream into a structured product.

Example Placement Memos and Presentations for Structured Products

Yes, we have some example documents and memos for this sector, but I’ll warn you in advance: these are very long and boring.

There’s one presentation from Ford Credit about the company’s asset-backed securities that’s a bit easier to get through, but the rest of these could easily put you to sleep:

- Ford Credit – ABS Investor Presentation

- Arkansas – Student Loan Asset-Backed Notes Memo

- Santander – Auto Loan Notes Memo

- Nelnet – Student Loan Asset-Backed Notes Memo

- Fannie Mae – Connecticut Avenue Securities – Mortgage-Backed Securities Memo

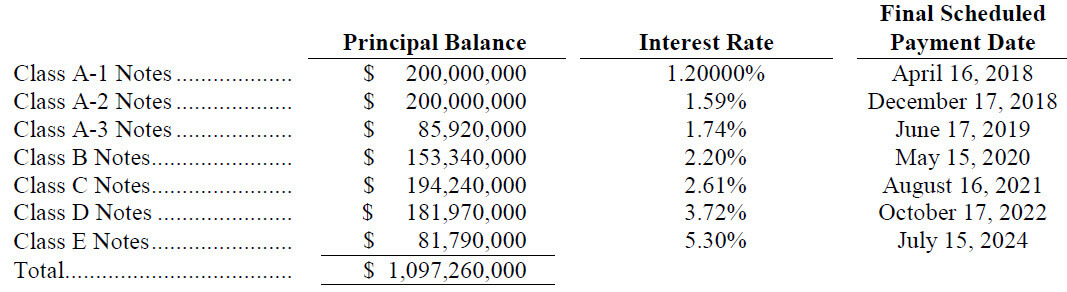

The most useful parts of these presentations and memos are the summary diagrams and tables that let you understand the deal terms quickly:

Structured Finance vs. Leveraged Finance

Leveraged Finance teams focus on high-yield, unsecured debt that typically funds transactions such as leveraged buyouts and M&A deals.

Structured Finance issues more complex instruments linked to the cash flows of assets, not entire companies, and they may even work with the LevFin team to finance certain deals.

The Leveraged Finance skill set is more applicable to corporate-level transactions, while Structured Finance is all about asset-level analysis.

Structure Finance vs. Debt Capital Markets

The DCM team works with plain-vanilla debt in which the pricing and terms are based on the company’s financial profile and credit rating.

Issuances in DCM lack the special terms common in Structured Finance, such as over-collateralization and subordination, and there’s little financial modeling work: the job consists of updating slides and gathering market data.

Structured Finance vs. Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS)

Mortgage-backed securities are a specific type of structured security, so the entire CMBS team could be considered a sub-group within Structured Finance.

The difference is that Structured Finance works with many other assets besides commercial real estate, while CMBS specializes in securitized issuances for all types of CRE properties (multifamily, office, retail, industrial, hotel, etc.).

The Top Banks for Structured Finance

The bulge bracket banks with large Balance Sheets tend to have the strongest groups here.

Expect to see JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Citi, Credit Suisse, and Deutsche Bank near the top globally and in the U.S.

If you go by the Bloomberg “Structured Note” league tables, you’ll see some less-familiar European banks as well, such as Landesbank Hessen-Thuringen Girozentrale, DZ Bank, BayernLB, and Landesbank Baden-Württemberg in Germany.

Then there are French banks such as Crédit Agricole and Société Générale and various others (HSBC, Standard Chartered, BNP Paribas, etc.) that work on dozens of deals per year.

I suspect there might be a classification issue with these rankings, so if you have an explanation for some of these banks, feel free to leave a comment.

Recruiting: How to Get Into Structured Finance

Recruiting depends on the roles you are targeting: do you want to be a trader, a structurer, or a banker?

On the trading side, refer to the articles on fixed income trading, sales & trading internships, and sales & trading interview questions for the details about the recruiting and interview process.

Structuring roles require something closer to “real math,” which means that a STEM degree – and maybe even a Master’s degree in a technical field – is quite useful.

Structurers use statistics, similar to actuaries at insurance companies, to estimate the potential losses from pools of loans.

It’s closer to the work you do at quant funds, so you should refer to that article for more recruiting details.

On the banking side, recruiting is similar to the standard IB process in terms of the requirements and timing, but there are a few differences:

- Premium for Relevant Work Experience – Since SF is so specialized, they want people who have worked in this specific area before, whether at a credit rating agency analyzing structured products or even a Big 4 firm auditing structured products.

- Classification Confusion – Banks classify the group differently, so you may apply to sales & trading (fixed income) instead of investment banking.

- Undergrad Hiring – Banks hire out of undergrad for these roles, but SF groups tend to be small, and the roles are not always well-publicized. So, you may have to do more networking legwork to have a good shot.

Certifications are close to irrelevant in this area because the skill set is so specialized.

In theory, the CAIA covers “Structured Products,” but it also covers many other fields, and it’s not a great use of time vs. gaining real work experience.

Example Structured Finance Interview Questions

The “fit” / behavioral questions and your story are the same anywhere, so we’re not going to repeat all of that information here.

Also, you could easily receive standard accounting, valuation, and financial modeling questions because cash flow-based modeling is still a part of the job.

Structured Finance-specific technical questions could come up, but they’re more likely if you’ve already had related work experience.

Here are a few examples:

Q: What does “securitization” mean, and why do companies do it?

A: See the explanations at the top of this article.

Q: What makes an asset attractive or not attractive for securitization?

A: Stable and predictable cash flow (or the perception thereof) is the most important factor.

On a pooled level, you also want loans whose default rates are relatively uncorrelated so that structured product features such as subordination can legitimately alter the risk/return profile of different tranches.

Q: What’s in a typical private placement memorandum (PPM) for a structured product?

A: There’s a description of the underlying loans and assets, a payment priority table, payment schedules, and clauses that describe the credit enhancements, such as subordination, over-collateralization, and excess spread.

Q: Suppose that you’re analyzing a student loan ABS. How would it differ from the analysis of other consumer ABS, such as ones for credit cards and personal loans?

A: One difference is that terms such as forbearance and deferred payments are much more common with student loans, so any cash flow model has to include those and properly reflect the payment priority to different investor groups.

Also, the federal government in the U.S. is more active in the market and may guarantee or even forgive student loans in certain periods, so the possible outcomes are less predictable than with other consumer ABS.

Q: What’s the typical structure of a collateralized debt obligation (CDO)?

A: A typical CDO might have 1-2 “senior” tranches, a mezzanine tranche, and a junior or “equity” tranche.

The yields and risk increase and the credit ratings decrease as you move from top to bottom, and the junior tranche investors will absorb the first losses in the case of a default.

The senior tranches are the safest and tend to represent the highest percentages in the CDO (often 70-80% of the total).

Q: What is a “true sale,” and why is it important?

A: In a “true sale,” the originator (company) completely transfers assets to the issuer and removes the assets from the originator’s Balance Sheet.

Effectively, a “true sale” ensures bankruptcy remoteness, which is a key credit enhancement that reduces the risk of structured notes.

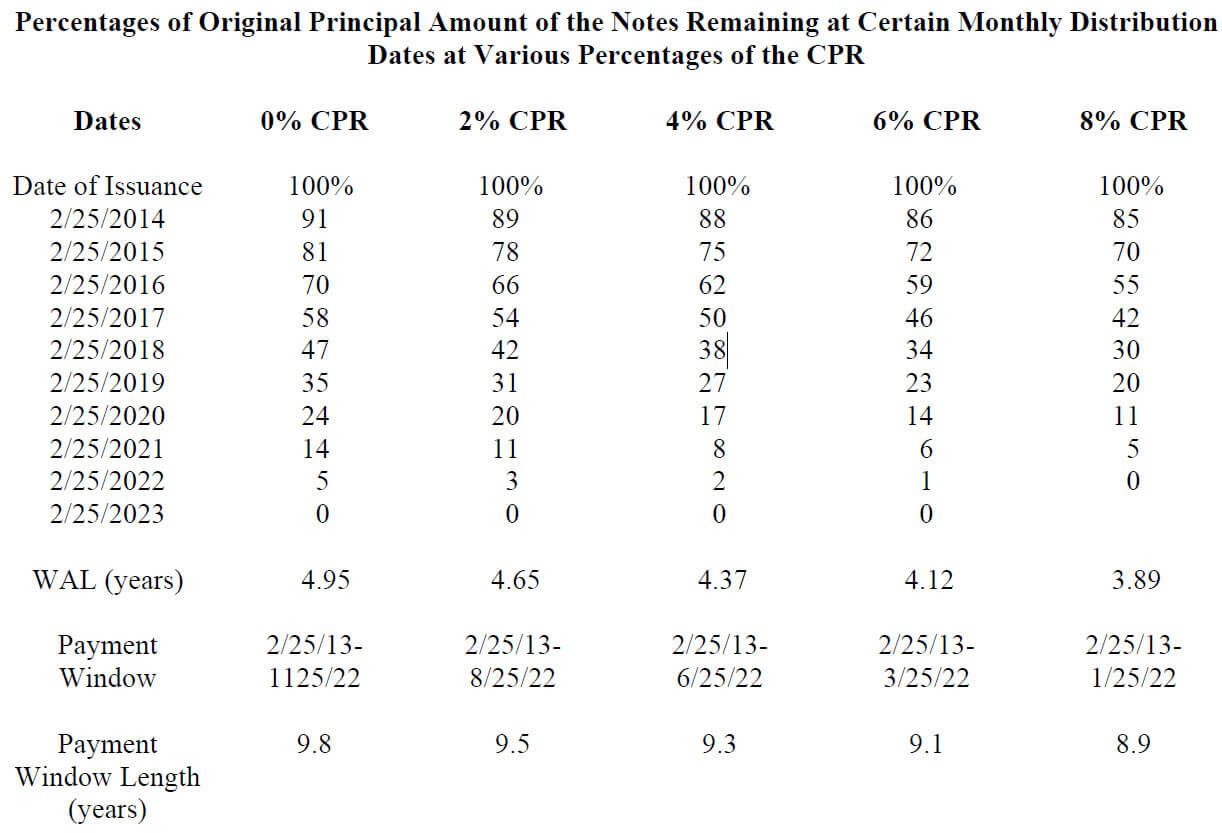

Q: What are the CPR and CDR, and how do you calculate and use them?

A: The CPR is the Conditional Prepayment Rate, and it represents the annualized percentage of an existing loan pool that is expected to be prepaid.

You can estimate it with: CPR = 1 – (1 – Single Month Mortality Rate) ^ 12

The “Single Month Mortality Rate” equals the actual payments made minus the scheduled payments in a month, divided by the loan principal in that month.

For example, if there’s a $200,000 mortgage, the scheduled interest payment in a month is $1,000, and the scheduled principal repayment is $2,000, and the borrower repays $4,000:

CPR = 1 – (1 – ($4,000 – $2,000 – $1,000) / ($200,000 – $2,000)) ^ 12 = 5.9%.

If these numbers hold across the entire loan pool, investors can expect ~6% of the entire pool to be repaid early each year.

The CDR is the Constant Default Rate, and it measures the percentages of loans within a pool that have fallen more than 90 days behind on payments.

CDR = 1 – (1 – New Defaults in Period / Non-Defaulted Pool at the Beginning of Period) ^ Number of Periods in Year.

For example, if there’s a beginning mortgage pool of $100 million and $2 million in new defaults in one quarter of the year:

CDR = 1 – (1 – $2 million / $100 million) ^ 4 = 7.8%.

The CPR and CDR are used to analyze asset-backed securities and determine appropriate prices and other terms for potential investors.

All else being equal, an ABS with a low CPR and low CDR is more attractive than one with higher rates for one or both of those.

Placement memos for structured products often include analysis and estimates based on these metrics as well:

Structured Finance: The Day-to-Day Job

As a banker, the day-to-day job in Structured Finance is similar to what you might experience in other capital markets teams such as DCM or ECM.

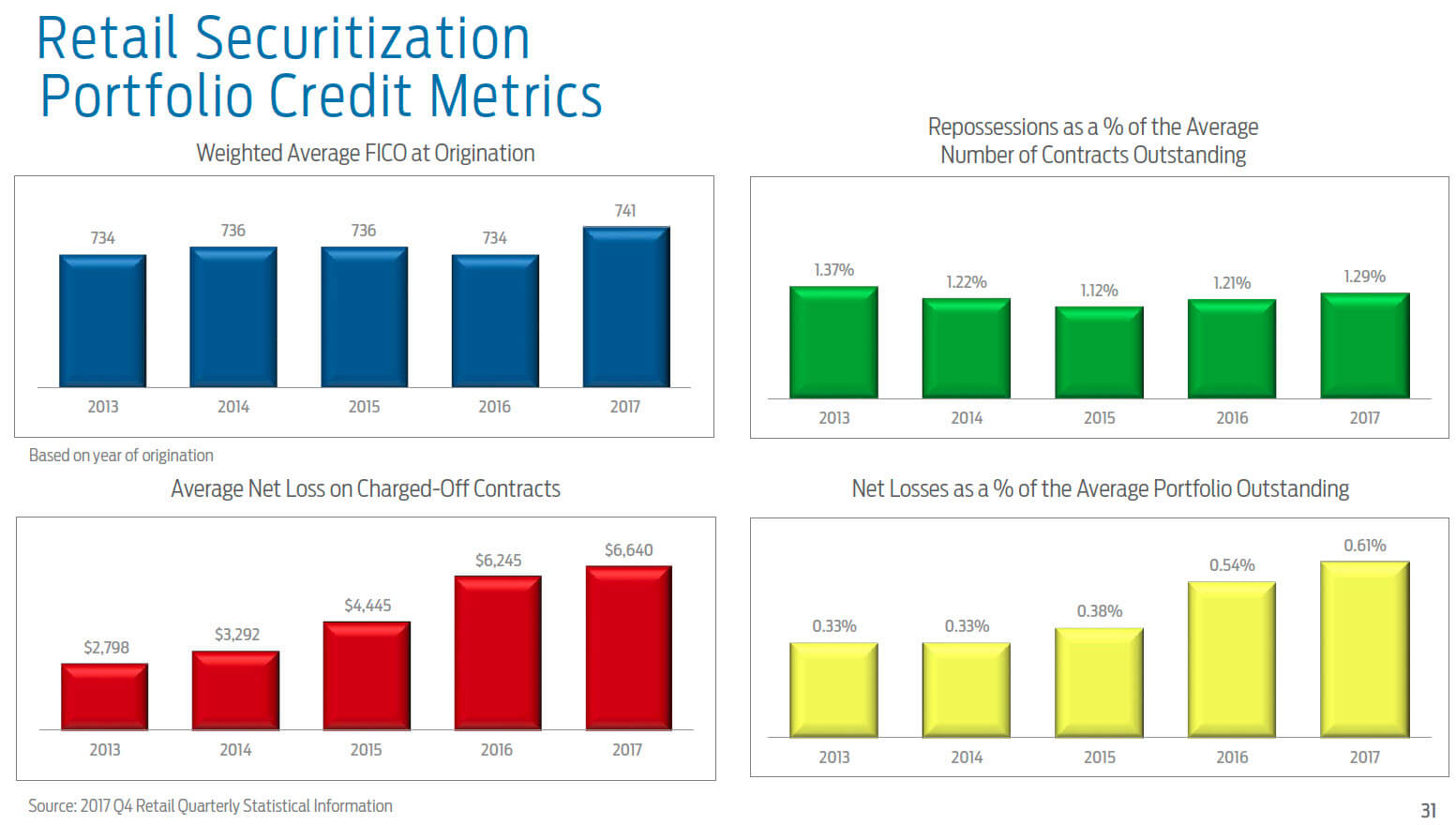

That means slides showing the features of recent issuances, a fair amount of market monitoring, and also “loan performance tracking.”

This last one is specific to Structured Finance, and the purpose is to show how the collateral underlying structured notes is performing.

You’ll gather and present data on defaults, overall credit quality, and metrics like the CDR and CPR described above. Here’s a simple example from the Ford Credit ABS presentation:

Bankers are responsible for coming up with ideas for new deals, doing a bit of “cash flow modeling,” and creating the marketing materials for the sales team.

There are two types of financial modeling work in this group: analyses in which you project the cash flows and repayments to different groups under different scenarios – similar to waterfall modeling in real estate – and statistics-heavy, quantitative modeling based on Monte Carlo simulations (and other methods).

You don’t do this stat-heavy modeling as a banker, but you do use the output of the analysis, such as the default probabilities for different types of loans, as inputs into your Excel models.

And the Excel models you do create are much more likely to be “cash flow only” instead of traditional 3-statement models.

Structured Finance Salaries, Bonuses, Hours, and More

Salaries and bonuses in Structured Finance are very similar to investment banking salaries, so please refer to that article for the details.

Managing Directors may earn a bit less than standard industry or product group MDs because the deal sizes are often smaller, the fee percentages are a bit lower, and banks charge different fees depending on how much custom work is required in deals.

The hours tend to be less than in M&A or industry teams and closer to what capital markets professionals and traders experience: an average of ~12 hours per weekday.

There are sometimes last-minute/weekend emergencies, but since it is more of a markets-based role, they’re less frequent here.

And since it’s a very specialized area, team sizes are also smaller than in DCM/ECM, which means a flatter structure and more responsibility and client exposure early on.

Structured Finance Exit Opportunities

And now we arrive at the biggest downside of Structured Finance: the exit opportunities aren’t so great.

You have a low chance of getting into traditional private equity unless you have previous M&A, Leveraged Finance, or industry coverage experience.

Some hedge funds invest in structured products, so your chances are a bit higher there, but you still won’t be a strong candidate for traditional long/short equity or global macro funds (for example).

And fields like venture capital and corporate development are a huge stretch – unless, in the latter case, the company happens to issue structured notes all the time.

The problem with all these exit opportunities is that the modeling/deal skill set is very different because you rarely do corporation-level analysis in Structured Finance.

You don’t gain experience valuing entire companies, analyzing M&A deals, or even modeling leveraged buyouts, so your experience is not immediately relevant to other teams.

That said, with certain esoteric structured products, the business fundamentals and accounting nuances may matter – so if you’ve had that kind of exposure, you might have a better chance with some of these exit opportunities.

Another option might be a credit fund, including ones housed within hedge funds, PE firms, and even distressed PE firms, as your skill set is more relevant for credit analysis.

Something like the CMBS group at a bank might also be an option – but they tend to care more about real estate expertise than structured product experience, so your mileage may vary.

Aside from these, the most likely exits and long-term career options are:

- Move to another team at your bank or use lateral hiring to move to another bank (but don’t wait more than a few years, or it gets difficult).

- Work in corporate finance at a normal company, such as a client you’ve advised on an ABS issuance that tends to issue many structured securities.

- Join an insurance company, asset management firm, or even a pension fund that invests in structured notes.

- Stay in Structured Finance and move up the ladder.

Structured Finance: For Further Learning

If you want to learn more about the field, here are some recommended books:

- Structured Finance and Collateralized Debt Obligations: New Developments in Cash and Synthetic Securitization

- Introduction to Structured Finance

- Understanding Credit Derivatives and Related Instruments (More technical and better for statistical modeling)

- Credit Risk Modeling Using Excel and VBA

And before you ask: I’ve never seen a financial modeling training program for Structured Finance.

You may be able to find in-person classes or 1-on-1 providers that offer it, but the field is so specialized that no one has taken the plunge to create detailed online training yet.

Is Structured Finance Right for You?

If your primary goal in life is to win an offer in private equity at KKR or Blackstone, the Structured Finance team is not for you.

The modeling and deal work are very specialized and don’t translate well into most other roles.

And if you want an internship or entry-level job at a bank, it’s not worth the effort of studying these specialized technical questions and networking specifically with this one group.

That said, Structured Finance offers plenty of advantages for the right person:

- Deals can be far more interesting than the average acquisition or capital raise since each transaction might have custom terms. More creativity is required to figure out the right structure for clients and stress-test your ideas.

- There’s more modeling work and analysis than in other capital markets teams like ECM and DCM.

- But the hours are still similar to those in capital markets teams, and entry-to-mid-level compensation is about the same.

- You can also get into Structured Finance from a credit rating agency or Big 4 firm if you have experience analyzing or auditing structured notes at one of those.

- And if you want a long-term career in the group, the skill set, deal experience, and client relationships are so specialized that it will be difficult to replace or outsource you.

Just hope there’s never a repeat of 2008, and Structured Finance might offer you the well-structured career you’ve been seeking.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Hi Brian, thank you for the article and for the detailed breakdown of the different sides of structured finance. I am going to be working on the banking side of structured finance for my first full-time job experience, which is fine by me since I am not interested in working in private equity.

I am not set on my long-term ambitions, but some things that I would like to try out after structured finance (in an ideal world) are sell-side research, M&A, a sector coverage team, and leveraged finance, culminating in seeking an unstructured recruiting path into a buy-side research/equity analyst role at a hedge fund. I chose to pursue structured finance because I want to become well-versed in debt at this early stage in my career and with cash flow modeling, but I feel like my true, long-term passions lie more with investing in public equities.

To that end, what path would you recommend I seek?

Thanks. If you want to do public equities investing, you should try to move to sell-side research or a good industry group. M&A and LevFin can also work, but coming from Structured Finance, it’s usually better to go to something more directly related to the public markets.

Hi Brian,

Which of the following paths would be the easiest to make a lateral move to IB?

1. Work in Structured Finance as a credit rating analyst, move to the Lev Fin team in a CRA, then trying to win a role in Lev Fin team in IB

2. Work in Equity Research at a boutique, move to Equity Research at an IB, then trying to switch to M&A or Lev Fin team in IB

3. Work in Equity Research at a boutique, move to Valuation team at Big 4 or professional services firm, then trying to switch to M&A or Lev Fin team in IB

Any thoughts would be appreciated.

Path #2 is probably best, followed by Path #1, followed by #3. It’s always easier to move around internally at a bank than to join from an outside firm, and LevFin at a CRA is probably a bit more relevant for LevFin at a bank than a Big 4 / other valuation role is for LevFin.

Hi Brian,

I’ve just accepted an offer for S&P credit rating analyst. I networked with a guy from SF so mentioned in my interview that I want to start on SF credit rating. Since I have back office Ops experience in mortgages I’m sure they’ll place me there. Just wondering if you think I should request to move to Leveraged finance CRA then lateral to a bank lev fin and then maybe PE, or you think staying in CRA SF is a good way to build niche skills that will make banking recruiting easier in their SF teams?

It depends on your goals. If you want to work in Structured Finance in the long term, stay in Structured Finance at the CRA. If your goal is to get into PE eventually, move into more of a generalist role, such as LevFin at the CRA and then LevFin at a bank. You are probably not going to move directly from any SF role into PE, so if you want more of a generalist option, you should transfer early.

Hi Brian,

Thank you for this article and many others which have been helpful!

I was wondering if you had any knowledge on the ease or if structurers in an IB can rotate from the securitised products groups to other teams more closely related to traditional IB so that it leads to exit opps such as those leading to KKR, Carlyle – type buy side firms.

Would a possible lateral be FIG or perhaps something like Leverage Finance?

Many thanks

I do not know offhand, but as with most specialized groups, you can usually move around to other teams within IB if you do so early on (within the first 2-3 years of joining). The longer you wait, the more you’ll be “stuck” in Structured Finance (or any other specialized group). It’s rare to move directly from SF to something like mega-fund PE, but people do often switch from other teams into standard IB industry groups and then into PE from there. Yes, FIG or LevFin would be good options.

Hi Brian,

Quick question: I have an offer in Germany for structured finance real estate in a commercial bank. Do you think it would be a feasible stepping stone to REPE?

Yes, but it’s probably a better pathway into RE lending or debt funds since Structured Finance also deals with debt.

does this group trade stuff like BNPL debt?

It could be part of the consumer portfolio that a Structured Finance team works on, but it has to be tiny next to traditional credit cards, auto loans, etc. I’m also not convinced it’s going to be huge going forward – it seems like it was more of a pandemic-induced spike with everyone staying at home and shopping online.

Great article. I actually am interviewing with the big four for their SF transactions in originations for CLOs but also am interviewing with a large bank in their Corp Treasury as an internal consultant.

I previously worked with specifically CLO’s for a bank as trustee analyst so I have a niche in SF.

Which pathway would you recommend…SF (buys side working with IB’s on the origination of CLOs) or Big bank Corp Treasury – global funding?

Big four one is in NYC and other one in Charlotte.

Is NYC experience something a finance professional should have? And can you tell me more about how the big four is involved in the origination process for SF?

Honestly, I don’t know enough about these options to give you real advice, but the Big 4 one sounds more relevant to me. Corporate Treasury at a large bank doesn’t sound that close to the type of deal work you do in IB/other fields, so despite the brand name, I’m not sure how much it will help you.

Working in NY helps, or at least it used to, due to the high number of exit opportunities and firms based there, but it has become less of a factor over the past few years due to remote work, on-and-off work from home, etc.

I can’t say how the Big 4 is involved in SF origination in detail because this article just covered SF at the large banks. But I would assume it’s similar but with smaller deals.

What do you think about a career in Structured Finance and Real Estate? IMO, both fields are highly specialized, but it seems that Real Estate has more options for people who want to transition into M&A roles or transaction advisory roles later on. It also appears that Real Estate / Infrastructure funds are a lot more common than structured credit funds.

I would agree with your comments. Both are specialized, but RE still gives you more options than SF because there are so many other jobs in and around RE, with many fewer in and around SF.

Hi Brian, great article. I have a situation that I was hoping for your advice on. I just received an offer for one of the big 3 credit rating agencies for next summer. All the people I’ve spoken to their have been really nice and it seems like there is a great culture there. I have also heard that they give you a ton of responsibility/opportunity to learn, so it’s an excellent place to start one’s career and move on after a few years. On the other side, I have a Superday with a BB IB next Tuesday, which I think would definitely make sense to take if I get the offer.

The question I have comes down to 2 firms that I have interviews with and would have to ask to accelerate my process before I have to sign my credit rating offer- BTIG and Cantor Fitzgerald. I have not heard much about either of them, so I was curious if you think that those firms would definitely be better options than credit ratings, if my plan as of now is to hopefully move to private credit fund/direct lender after a few years at one of these options. Thanks!

I think anything in investment banking at almost any firm is better than a credit rating agency offer, assuming you can actually tolerate the hours/lifestyle of IB enough to benefit from it. There may be some exceptions for tiny regional boutique banks without much deal flow, but both those firms are more in the middle-market category.

Hi Brian, thanks for this article! Was hoping for some advice regarding my situation,

I graduated from oxford in the uk and had a return offer at a big asset manager (blackrock/schroders). Unfortunately I did unexpectedly badly for finals which determined my entire uni grade and got a 2.2 (equivalent to just below a 3.0 GPA), thus losing the offer. I was wondering how I might work my way back into a role in finance. I have a good idea of what my options are and they’re mainly:

1. apply to big 4 and lateral later

2. cold call a bunch of IB boutiques in london

3. do a masters to improve my grade (I actually enjoy academia and my grades before finals were really good)

4. apply to some off-cycle internships at BBs (might explaining my grade in the cover letter help?)

The main problem now is that I’m not sure how I should prioritize these options. I don’t really have a good sense of how much the 2.2 is offset by the fact that I went to oxbridge and that I do have a strong CV otherwise.

I think your best bet is to do the Master’s to improve your grades because that seems to be the main obstacle here, and then recruit for IB roles during/after the Master’s. Grades and A-Level scores etc. still matter a lot in the UK, so I’m not sure how well you could offset this without another degree.

You could try cold emailing boutique IB firms and even BB firms, and it may work, but then you’ll just have to spend more time at a smaller firm or in an internship before switching again. But if you don’t want to pay for another degree, maybe this approach is better.