Value-Add Real Estate: What Makes It Different, and Why You Should Invest – Maybe

Along with core real estate, value-add real estate, also known as “value-added real estate,” is one of the main categories in the sector.

It’s one of the many strategies that real estate private equity firms use to acquire, operate, improve, and sell properties.

And it’s the strategy that almost sounds too good to be true.

It’s not quite as risky as equities, but it offers a higher potential return than most fixed-income assets.

And if an investment firm executes a value-added deal properly, then the deal’s outcome has more to do with property upgrades and less to do with the overall market.

This description makes value-add real estate sound simple – but, as usual, there are many nuances that most sources skip over:

The Main Real Estate Investment Categories

We covered the main categories in the article on core real estate, so please refer to that for the details.

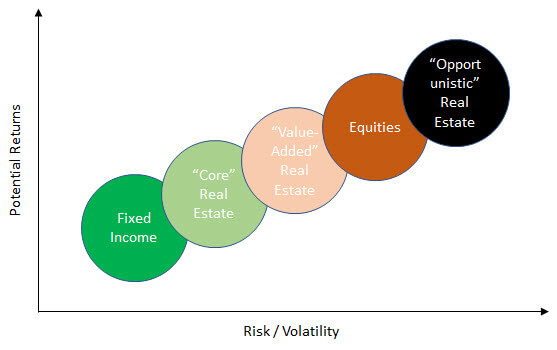

My favorite summary graph for the sector is this one:

Value-add real estate falls squarely in the domain of private equity firms that are willing to take on more risk.

What Makes Value-Add Real Estate Different?

Many articles state that the value-add category is different because properties change significantly, leverage tends to be higher, cash flows fluctuate more, and a higher percentage of the returns come from capital appreciation.

These points are generally true, but I would frame this discussion in terms of real estate financial modeling instead.

In other words, how are Excel-based financial models, such as the pro-forma, different for value-added deals?

There are five main differences vs. core deals:

- Renovation/Redevelopment Costs – The sponsor will pay for these to improve or upgrade the property, and they will reduce Cash Flow to Equity or require higher upfront funding from the sponsor.

- Penalty During the Renovation/Redevelopment Period – For example, a property’s occupancy rate might decline while the renovation is taking place, and some units are not available.

- Benefit Following the Renovation – For example, the occupancy rate or average rent might increase once the renovation is done.

- Permanent Loan Refinancing – There is often a real estate loan refinancing once the renovation finishes and the property stabilizes. The property’s risk profile changes when it goes from “under renovation” to “stabilized,” so it attracts a different type of lender (see: more on real estate lending).

- Exit Assumptions – Unlike in core deals, in value-added deals it is reasonable to assume a lower Cap Rate upon exit (meaning a higher property value) because the sponsor has spent time and money to improve the property.

The key point is that value-add real estate is all about trade-offs.

For example:

- If you acquire a hotel for $100 million and then pay $10 million to renovate it, will that renovation boost the average daily rate (ADR) and occupancy rate by enough to justify the expense? Is it worth it to lose 50% of the rooms while the renovation takes place?

- If you complete interior unit upgrades on a multifamily property, will you be able to raise the rents enough to justify the expense and downtime? Will the property go from Class B to Class A and attract wealthier tenants?

- If an office building currently has a 70% occupancy rate, can you complete a renovation that attracts two new tenants, boosting the occupancy rate to 90%? And can you convince the existing tenants to move to longer-term leases?

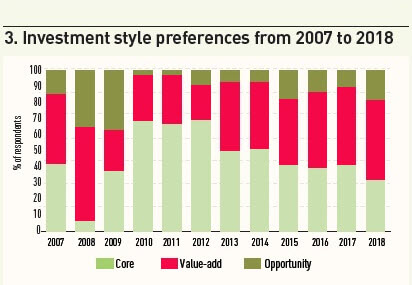

When the market is at a cyclical low, such as in 2009 – 2010, investment firms tend to acquire underpriced, stable properties and wait for rents and prices to recover.

There’s no reason to take risks on new developments or renovations if prices have just fallen by 50% and there are plenty of bargains in the market.

But as the cycle progresses, investors start moving to value-add and opportunistic strategies because they can’t rely on a gradual recovery.

This graph from IPE Real Assets and Preqin sums up preferences over the cycle quite well:

Value-Add Real Estate Returns Profile

To illustrate the returns profile, we’ll look at that same example that we used for core real estate, but change the assumptions significantly.

Instead of linking the outcomes to the market itself, we’ll link them to the success or failure of the renovation.

The main assumptions are:

- Property Type: Multifamily

- Units: 76 units with an average size of 573 square feet per unit

- Average Monthly Rent per Square Foot: $1.33 ($764 per unit)

- Location: Phoenix, Arizona

- Acquisition Price: $7.1 million (6.0% Going-In Cap Rate)

- Loan to Value (LTV) Ratio: 70%

- Loan Terms: 5% fixed interest; 30-year amortization; 5-year maturity

- Exit Cap Rate: Varies from 5.5% to 6.5% depending on the outcome of the renovation

For simplicity, we are not assuming a permanent loan refinancing here.

Currently, tenants in this property are paying a 25% discount to market rents, and the property has a 5% vacancy rate.

The investors believe that with modest renovations, representing 10-15% of the property’s price, they could greatly significantly increase in-place rents and reduce that 25% discount.

The downside is that the vacancy rate will increase to ~25% during the two years of the renovation, as certain units become unavailable.

Also, even after the renovation is done, the vacancy rate may remain higher than the original 5% simply because rents will increase.

Finally, the 25% discount to market rent is unlikely to “disappear”; it might decrease, but it will still be there in some form.

To assess this deal, we created three main scenarios:

- Highly Successful Renovation (Upside Case): The vacancy rate eventually declines to 5%, the discount to market rent falls to 5%, and the Exit Cap Rate falls to 5.5% since the property is now more appealing.

- Solid Renovation (Base Case): The vacancy rate eventually declines to 10%, the discount to market rent falls to 10%, and the Exit Cap Rate decreases to 5.75% since the property is now slightly more appealing.

- Failed Renovation (Downside Case): The vacancy rate remains elevated, at 15%, the discount to market rent only decreases to 17.5%, and the Exit Cap Rate rises to 6.5% since the property is now worse from an operational perspective.

Here are the numbers in each scenario:

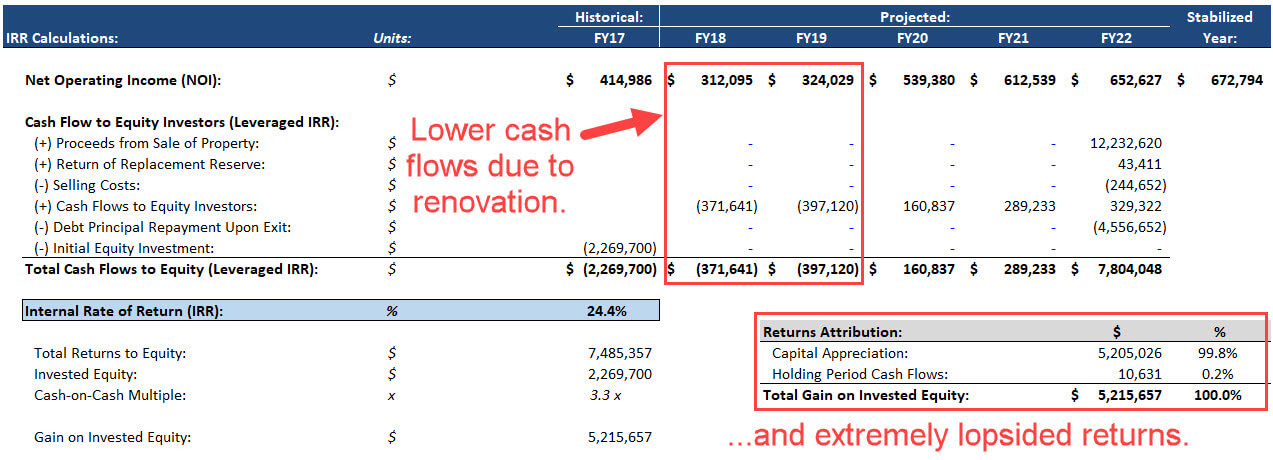

Scenario #1 – Highly Successful Renovation (Upside Case)

In this case, the renovation goes exactly as planned, resulting in a 24% IRR and 3.3x cash-on-cash multiple:

The property generates little cash flow during the holding period, mostly because the vacancy rate rises significantly in the first two years as the renovation takes place.

Therefore, even in a highly successful case, most of the returns come from capital appreciation (i.e., the lower Cap Rate and higher NOI by the end).

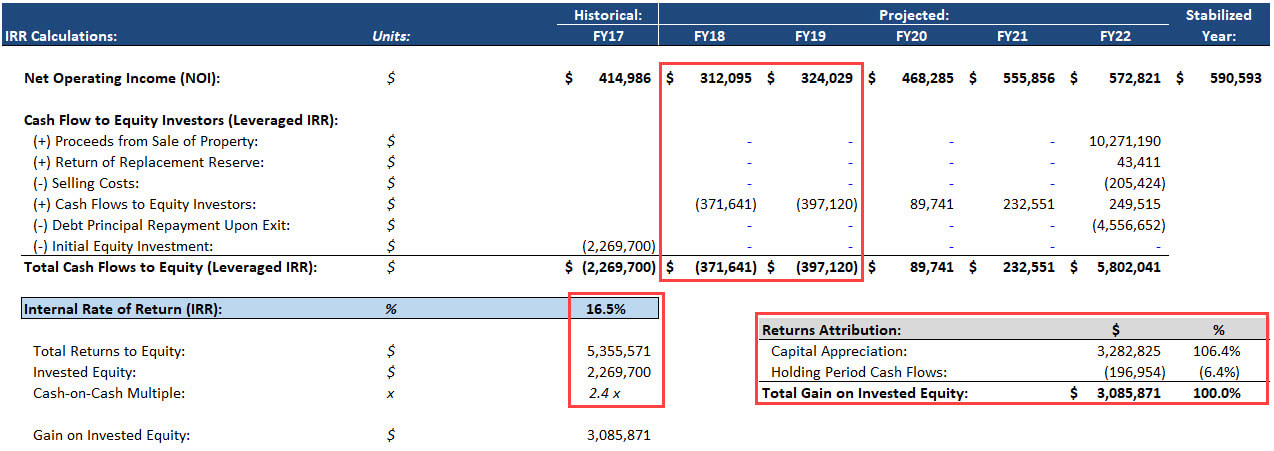

Scenario #2 – Solid Renovation (Base Case)

In this case, the renovation achieves some, but not all, of its targets.

And that’s OK because the IRR is still 17%, with a 2.4x cash-on-cash multiple:

The returns are even more lopsided toward capital appreciation; total cash flows during the holding period are negative.

Scenario #3 – Failed Renovation (Downside Case)

In this case, the renovation does not go according to plan, and the sponsor spends significant time and money to achieve very little.

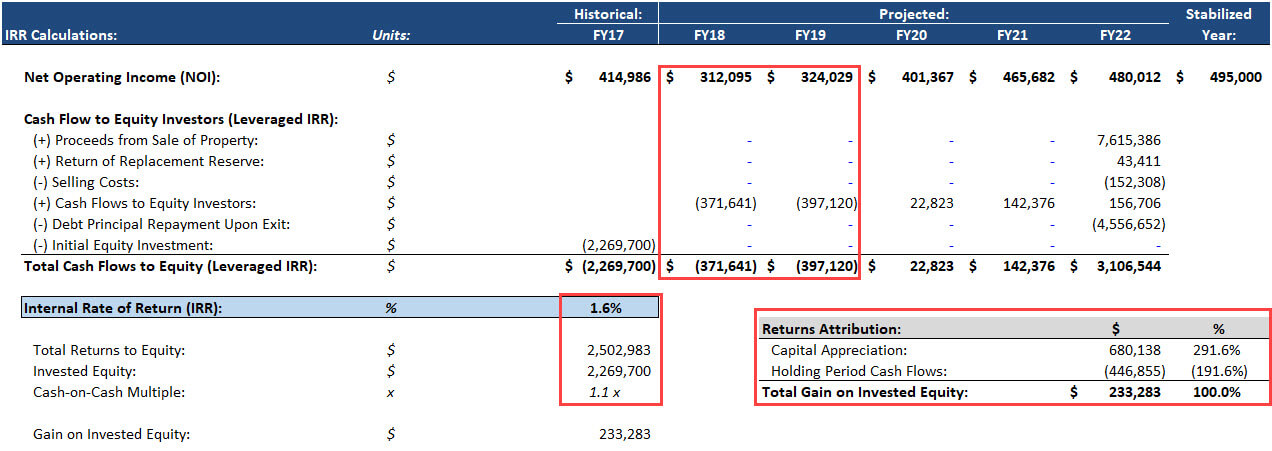

That results in a 2% IRR and a 1.1x cash-on-cash multiple:

The returns are even more tilted toward capital appreciation because the cash flows are even more negative.

So, Should We Do This Deal?

At first glance, you might say, “Yes! We avoid losing money in the Downside Case, and the Base and Upside Case result in IRRs in the 15-25% range.”

But there’s more to it than that.

First off, we did not look at a true worst-case scenario where there’s no improvement from the renovation at all.

Under that assumption, the IRR would almost certainly turn negative.

Also, we haven’t verified these numbers or done a real-life feasibility check.

Sponsors often over-sell value-added deals and make aggressive claims about their ability to boost rents – claims that are not supported by the data.

For example, if this property is in the middle of an area inhabited by cocaine dealers, criminals, and tents filled with heroin addicts, no renovation in the world will boost its in-place rents by 33%.

Finally, we did not consider the other risk factors common in these deals, such as cost overruns, delayed construction, and reputational damage for the property due to the removal of too many units at once.

So, the real-life answer here is a strong “maybe.”

Value-Add Real Estate: Why Work in the Field?

You would like value-added real estate deals if you like to get your hands dirty and make significant changes to properties rather than just searching for overlooked gems in promising markets.

The financial modeling/technical work is more complex than in core real estate, but you still need to understand commercial real estate market analysis, including cycles, supply/demand, and demographics.

Real estate private equity firms like value-added deals because they offer potential returns above the range normally offered by core properties.

So, you’re more likely to work on these deals in private equity and at other alternative investment firms and less likely to do so at pensions, endowments, and other conservative institutions.

Why Invest in Value-Add Real Estate?

It goes back to that graphic at the top: value-added deals offer potential returns close to those of equities with, arguably, a lower risk profile.

Even if a renovation goes poorly, the property will still generate cash flow, and the land and building will always be worth something.

The chances of a total wipeout, or even a 40-50% decline, are lower than in equities – at least if you invest in a variety of funds across different markets.

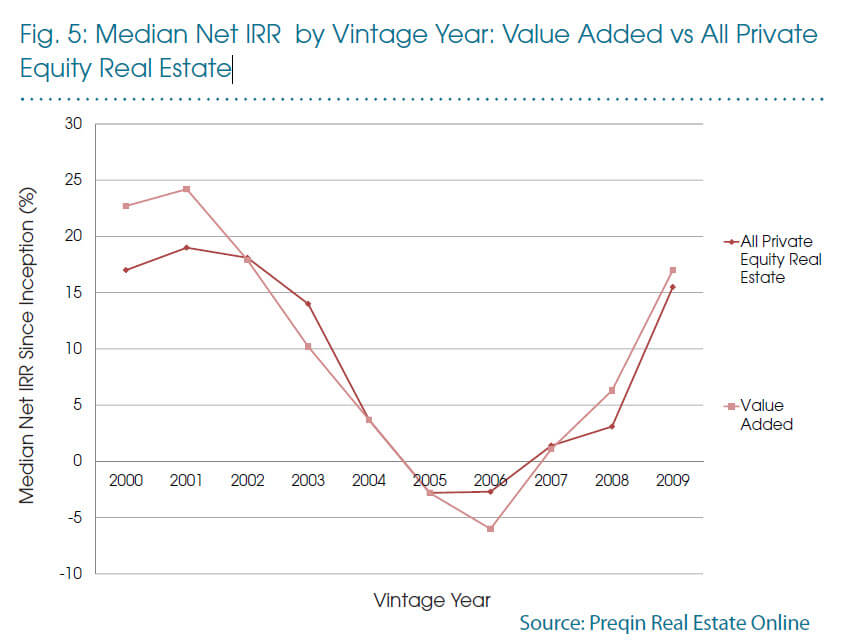

This graph from Preqin sums it up quite well:

So, yes, value-added funds started just before the crash didn’t do so well, but the average IRR only fell to (5%) in that time – not a complete disaster.

Personally, I have invested a bit in value-add real estate, but less than in other categories in the sector.

Part of this is my personal bias: I like very safe assets and very risky ones, but I avoid ones in the middle of the road.

Also, it’s harder to gain access to value-added deals as an individual investor.

REITs don’t focus specifically on this deal type, crowdfunding sites tend to have fewer value-added deals, and buying properties outright and renovating them is out of the question for most individuals.

The best access usually comes via real estate private equity funds, which are off-limits for most retail investors.

But if someone could bring value-added deals to the masses, that would truly add some value.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Thanks for an another great article! Though, there is a more profitable option! why not buy yourself real estate, make your loss-making company to lease it and make more money by putting a ridiculous multiple to investors? Oh wait, there already is… (+$5.4 mil for changing the company name)

Thanks! I’ve thought about doing a WeWork valuation, similar to the Uber valuation here a few months ago, but it’s such a joke of a company that I almost want to list $0 in giant font size in an Excel sheet and say that’s their value.

But who knows, if I have more time next month, I might actually do it… especially if WeWork proceeds with its IPO.