The IPO Process – and Why Companies Are Increasingly Bypassing It

A few decades ago, the initial public offering, or IPO process, was seen as the end goal for startups and high-growth private companies.

Before a company “goes public,” it is private, which means that it has a small number of shareholders and that its shares cannot be bought or sold on public stock exchanges such as the NASDAQ or NYSE (see more on private company valuation).

After a company goes public, a much wider group of individuals and institutions hold its shares, anyone can buy those shares on public exchanges, and the company must file regular reports about its financial performance.

Many private companies still aim to go public, but an IPO is no longer the best or only option.

There are important distinctions between “going public” and the “IPO process,” which we’ll delve into in this article:

- What is an Initial Public Offering (IPO)?

- Why Go Public via the Traditional IPO Process?

- The IPO Process, Part 1 – Pitch for the Deal and Select an Underwriter

- The IPO Process, Part 2 – Hold the Kick-Off Meeting

- The IPO Process, Part 3 – Draft the S-1 Filing

- The IPO Process, Part 4 – Pre-Sell the Offering

- The IPO Process, Part 5 – Conduct the IPO Roadshow

- The IPO Process, Part 6 – Hold the IPO Pricing Meeting

- The IPO Process, Part 7 – Allocate Shares to Investors

- The IPO Process, Part 8 – Start Trading

- The IPO Process: Long, Exhausting, and Expensive

- Direct Listing vs. IPO, and Why Direct Listings Are On the Rise

- Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) and Reverse Mergers

- Are These Trends Good or Bad for Investment Bankers? Will the IPO Process Ever Go Away?

- For Further Learning

What is an Initial Public Offering (IPO)?

Initial Public Offering (IPO) Definition: In an initial public offering, a private company sells primary shares (i.e., newly created shares sold for cash) to “the general public” (mostly institutional investors) for the first time and becomes a publicly-traded company in the process.

In addition to an IPO, a company could also go public via a direct listing, in which it does not sell new shares and does not raise capital.

To give a specific example, let’s say that a private company is currently worth an Equity Value of $1 billion according to its most recent round of funding.

It also has 100 million shares outstanding, so each share is worth $10.00.

In an IPO, this company might issue 30 million new shares, selling ~23% of its equity.

Its Equity Value would increase to 130 million * $10.00, or $1.3 billion, in the process.

But in a direct listing, its share count would remain the same, and its Equity Value would remain the same at $1 billion – at least until trading begins.

Finally, another option for going public is the reverse merger, in which a private company ends up owning a majority stake in an existing, public company

In a reverse merger, the private company also does not issue new shares and does not raise capital. We’ll cover this process toward the end of this guide.

Why Go Public via the Traditional IPO Process?

The “traditional view” is that companies go public via the IPO process for one or more of the following reasons:

- To raise capital – This capital could fund expansion efforts, acquisitions, or repayments of existing debt.

- To provide an exit for existing investors – Whether the company is PE-owned, VC-backed, or owned by a small group of individuals, the existing investors probably want to sell their shares at some point.

- To gain an acquisition currency – The value of most private companies’ stock is difficult to determine, so it is much easier to make acquisitions using stock once a company is public. Also, raising additional debt and equity is easier for public companies.

- To reward and attract employees – Employees who joined early accepted lower salaries and benefits in exchange for equity, and at some point, they’ll want to cash out. It’s also easier to attract executives if the company has publicly traded shares to use in compensation packages.

- To market themselves – Especially for lesser-known companies in “boring” industries, an IPO is a great way to increase prestige and attract new investors, partners, and customers.

Sometimes, legal or technical issues, such as a maximum shareholder limit for private companies in certain countries, force a company to go public as well.

Looking at this list of reasons, though, there is a problem: an IPO is only necessary for the first two benefits (and arguably a bit of the last one).

If a private company goes public via a direct listing or reverse merger, it also gains an acquisition currency and the ability to reward employees with publicly traded shares.

Even the second point here – providing an exit for existing investors – isn’t that big of a benefit in an IPO because:

- Existing investors rarely sell 100% of their shares right when the IPO takes place – they must sell their holdings gradually over time or risk “negative signaling.”

- And in a direct listing or reverse merger, existing investors could also sell their shares gradually over time, though it might take longer and incur more risk.

There are also plenty of downsides to the traditional IPO process: companies give up ownership and may leave money on the table if the IPO is not priced correctly, and there are high compliance and regulatory costs.

Oh, and companies really don’t like paying high fees to investment banks to “underwrite” a 6-12-month process where the banks arguably don’t add much value.

To explain these downsides in more depth, we’ll sketch out the typical IPO process below:

The IPO Process, Part 1 – Pitch for the Deal and Select an Underwriter

In most cases, banks have built up relationships over time with the company that wants to go public.

The company and its investors will then reach out to these bankers and invite them in to pitch for the business.

The IB Analyst and IB Associate then get to burn the midnight oil drafting a pitch book, which shows the bank’s proposed valuation and how it will run the process.

After all the pitches, the company selects banks for bookrunner and co-manager roles, mostly based on existing relationships, but also based on the pitches.

The banks’ IPO track records and their reputations with institutional investors also play a role.

Most companies select 1-3 banks as bookrunners and a few more as co-managers, but those numbers can be much higher in “large” IPOs of well-known companies (e.g., Facebook, Alibaba, Uber, etc.).

The IPO Process, Part 2 – Hold the Kick-Off Meeting

Everyone involved in the IPO – company management, auditors, accountants, the investment banks, and lawyers from all sides – attends this meeting (in-person or virtually).

You spend the day discussing the offering, the required registration forms, who’s doing what, and the timing for the filing.

Similar meetings continue throughout the process; they’re quite boring because the junior bankers are there just to take notes.

After the initial meeting, due diligence begins, and everyone involved with the deal calls customers, researches the market, and goes through legal, IP, and financial/tax documents.

Banks tend to focus on “customer calls,” and they assess the stability of the company’s revenue, market competition, and the key risks to the company’s sales growth.

The IPO Process, Part 3 – Draft the S-1 Filing

The first few steps of this process might take several months, and the result is the S-1 Registration Statement in the U.S. (the names vary in other countries, but it’s the same idea).

This document presents the company’s historical financial statements, key data, investors that are selling shares in the offering, the company overview, risk factors, and more.

Once it’s filed, the SEC (or equivalent government organization in other countries) reviews the document, and the company’s team of advisers responds with updated versions.

The company does not list its financial projections in its S-1 because it’s not allowed to give “forward guidance” until right before trading begins.

The IPO Process, Part 4 – Pre-Sell the Offering

As the team is working through revisions of the S-1, the company holds pre-IPO meetings with bankers and salespeople to plan out how to “sell” the offering to investors (see: our guide to the equity sales team memo).

The company can also start issuing a “red herring,” or preliminary prospectus, which is a shorter, sales-focused version of the S-1 that is missing key information such as the offering price and amount of proceeds.

Equity research analysts from the bank then meet with institutional investors and tell them about the company, and the equity sales team assesses investor interest to start estimating a price range for the offering.

After this pre-marketing work, banks amend the S-1 filing with a revised price range based on feedback from investors.

The IPO Process, Part 5 – Conduct the IPO Roadshow

In this part of the process, management traditionally traveled all over the country or world to meet with investors and market the company for 1-2 weeks.

But in the COVID era, these “roadshows” have gone virtual, and a good number might stay that way in the future.

The management team presents the company and answers questions, and banks also accept orders from institutional investors.

Banks use this data on the order volume and proposed prices to revise the price range.

It’s a tricky balancing act because the IPO outcome may be poor if the price is too high (since the share price could drop when the company starts trading) and if the price is too low (if the shares are priced and sold at $10.00, and the stock trades up to $25.00 on Day 1, they should have sold the shares at closer to $25.00 instead).

The company may also change the number of shares it’s planning to sell based on this investor feedback.

The IPO Process, Part 6 – Hold the IPO Pricing Meeting

Once the roadshow is over and the order book is closed, the management team meets with bankers and sets the final IPO price based on the orders received.

If a deal is oversubscribed, the company will price the company at the high end of the range; it will do the opposite for undersubscribed deals.

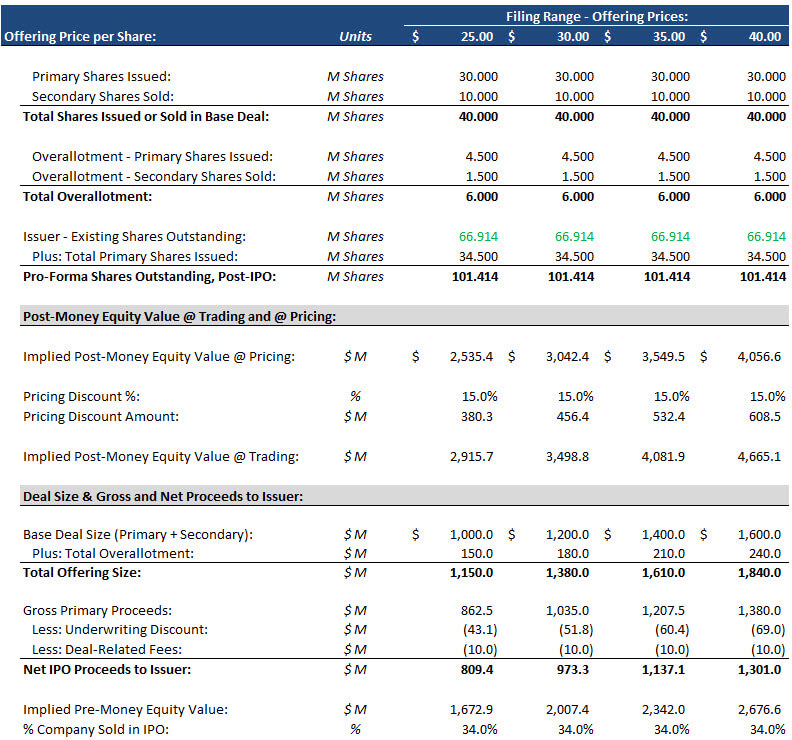

We get many questions about IPO valuation or IPO valuation models, and the short answer is that they don’t exist.

You value a company in an IPO process the same way you value any other company: with a DCF model and multiples from comparable companies.

However, you can build a model to show how the capital structure changes in an IPO.

We cover this in the YouTube tutorial below on “IPO valuation models” (yeah, they don’t exist, but this is the keyword people search for):

The basic idea is that the new shares offered in an IPO are sold at a discount to the institutional investors who place orders as an incentive for pre-ordering.

The company gets the cash proceeds from these orders, and its Equity Value increases.

Its Enterprise Value does not change because the increased Cash and increased Equity Value offset each other and because Net Operating Assets do not change:

If the market does not react well to the offering, the early investors could see big losses even after accounting for the 10-15% “discount” they received.

The IPO Process, Part 7 – Allocate Shares to Investors

Once the deal is priced, the banks’ equity syndicate team allocates shares to investors.

Banks try to allocate shares to investors who will be long-term holders of the stock, but they also keep in mind “the strength of the relationship” (AKA the future money-making potential of each investor).

The syndicate team usually works overnight to allocate the deal.

The IPO Process, Part 8 – Start Trading

Once the deal is allocated, the stock starts trading, and “the general public” can buy and sell shares.

However, there are often post-IPO provisions around the stock, such as lockup periods, quiet periods, and time windows for certain groups to buy additional shares.

A lockup period means that existing investors and employees need to wait a certain number of months or years before selling additional shares.

This period explains why companies that go public often experience a sharp share-price decline several months afterward – everyone is trying to cash out.

A quiet period means that the management and marketing teams of the company cannot share opinions or additional information about the firm for a certain number of days/weeks after trading begins.

The IPO Process: Long, Exhausting, and Expensive

You’re probably tired just from reading this description of the IPO process, and it’s even more exhausting for company management.

Altogether, it’s a 6-12-month ordeal that does not always result in a successful outcome.

It’s also expensive because banks traditionally charge 7% fees on the gross offering.

Going back to our example at the top, if this $1 billion private company sells 30 million shares for $10.00 per share, that’s a $300 million offering.

Therefore, the banks could earn fees of $21 million on this deal.

Sometimes the fees are closer to 3%, or even 1-2%, for very large and important deals.

People constantly debate whether or not these fees are “justified,” and it depends on how much bankers do to earn them.

If the bankers are taking a large and well-known company (Facebook, Uber, Alibaba, etc.) public, the company doesn’t “need” much help.

But if the company is smaller, lesser-known, or non-consumer-facing, it could benefit from the bank’s marketing and investor relationships.

A long time ago, banks used to assume substantial risk by buying the company’s shares before the IPO and then re-selling them (a “firm commitment”), which they used to justify their fees.

But this practice has become less common, and banks tend to take less risk in IPOs as a result.

Direct Listing vs. IPO, and Why Direct Listings Are On the Rise

Direct Listing Definition: In a direct listing, a private company goes public without underwriters and without selling new shares; it simply offers existing shares held by investors and employees and begins trading on an exchange.

NOTE: This is the “classic” definition of a direct listing, but it may be changing with a new proposal from the NYSE that will allow companies to raise capital in direct listings.

If we compare a classic direct listing to a classic IPO process, the differences are:

- Capital Raised: No new funds are raised in a direct listing.

- Underwriters/Fees: There are no underwriters in a direct listing; banks still “advise” the company, but they earn much lower fees (maybe half the traditional IPO fees).

- Roadshow: There is no roadshow, either in-person or virtual, in a direct listing. Instead, there’s a simple “Investor Day” where the company invites everyone to learn about them. Banks can advise on this presentation, but they do not solicit orders.

- Process and Requirements: The company and the SEC still go back and forth with the S-1 and revisions to it, but the company can offer forward guidance in a direct listing.

- Trading: Rather than a filing price range, there’s a “reference price” right before trading begins, followed by an auction to establish the price on the first day of trading. There’s also no lock-up period in a direct listing. These features can make the pricing of direct listings more accurate.

- Timing: It still takes at least 2-3 months to submit the S-1 and revise it based on the SEC’s comments, but the process is shorter than the IPO process (maybe about half the total time).

Direct listings are best for well-known, consumer-facing companies that don’t have an immediate need to raise more capital.

This explains why companies such as Spotify, Slack, Asana, and Palantir have used direct listings to go public (Palantir is not “consumer-facing,” but it is well-known).

The company does not get an immediate marketing bump, but it does gain an acquisition currency and the other benefits of being public.

If a private company’s shares have already been traded extensively on secondary markets, it’s also a prime candidate for a direct listing because its share price is easier to determine.

Finally, the auction on Day 1 of trading helps avoid major problems, such as getting the offering price wrong by 50%+.

And before you ask: there’s no such thing as a “direct listing financial model” because no corporation-wide transaction occurs.

No new money is raised, and the company’s capital structure does not change.

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs) and Reverse Mergers

You’ve probably seen the news about the “SPAC boom” and how everyone from Paul Ryan to Bill Ackman is getting into the game.

The idea here is that a “shell company” (i.e., an empty corporation with no products or employees) goes public via an IPO and raises funds from institutional investors, and then seeks out private targets.

When this shell company makes an acquisition, it issues so many shares that the target, not the acquirer, ends up controlling the new entity.

This is why the deal is labeled a “reverse merger” – unlike in a traditional acquisition, the target ends up controlling the new company.

If we continue with the startup example from above, where the company had an Equity Value of $1 billion and 100 million shares outstanding:

- SPAC: Maybe a SPAC interested in this startup has already gone public, and it has 10 million shares outstanding at $20.00 each, for an Equity Value of $200 million.

- Transaction Structure: The SPAC decides to make an offer for this startup. It issues 50 million shares to acquire the startup for a total price of 50 million * $20.00 = $1 billion.

- Result: The SPAC now has 60 million shares outstanding, but the startup target owns (50 / 60), or 83%, of the combined company. Also, the startup is now effectively a “public company” because the acquirer was a shell corporation.

Reverse mergers can happen in other ways as well – for example, a “real company” could issue a huge amount of stock to acquire a private company, and the private company could end up owning the majority of the combined entity.

Effectively, that lets private companies “go public” without going through the full IPO process.

Why would a private company bother to go public via a SPAC or reverse merger?

The short answer is speed and simplicity.

Since the SPAC is a shell corporation, it can complete an IPO much more quickly – a few weeks up to a few months rather than 6-12 months.

Underwriting fees also tend to be lower, and there’s no price uncertainty.

Also, the SPAC will be dissolved (with funds returned to investors) if it doesn’t complete an acquisition within ~2 years.

And if the SPAC investors don’t like a proposed acquisition, they can sell their shares (in theory).

SPACs are quite similar to the search fund model, where someone raises capital and then has a few years to find a company to acquire.

The difference is the scale, as SPAC targets can be multi-billion-dollar companies.

If a private company goes public via a reverse merger, it still does not raise new capital or get much of a marketing benefit.

However, it does get the other benefits, it retains more ownership than it would in an IPO, and it spends less time and money on the process.

But there are also disadvantages, such as the fact that deals can easily fall apart.

The private company is “going public” by getting exactly one shell company to issue shares to acquire it, and if that company or its investors change their mind, the deal’s off.

Also, there’s no guarantee that a specific public company will pop up and express interest in a specific private company, so the process can be quite random.

(Some SPACs have also been known to be regarded as “SCAMs” but that’s for another time–read about The Great SPAC Scam here.)

Are These Trends Good or Bad for Investment Bankers? Will the IPO Process Ever Go Away?

The short answer is that these trends are good for companies and investors because they provide more options for going public.

If a company does not need to raise capital, it can use a direct listing or reverse merger.

But if it does need capital, or it needs institutional investor relationships, it can use a traditional IPO.

But these developments are bad news for investment banks because they effectively reduce fees for capital markets transactions.

Traditionally, IPOs had been especially lucrative because banks could earn up to 7% of the gross proceeds in fees.

But if companies start bypassing the process with direct listings and reverse mergers, equity capital markets revenue at banks will decline.

Banks will still earn something, but it won’t be a 7% fee on gross proceeds anymore.

The traditional IPO process will never die because many lesser-known companies do need capital, marketing, and investor relationships.

But it will change over time, and eventually, it might resemble the direct listing process.

For Further Learning

If you want to learn more about these topics, please see:

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

He elaborates briefly in a depth understanding. I never found a course like this. Following this stuff made an additional resource for IPO preparation for my employer.

Thanks!

This was really helpful and interesting

Thanks!