Negative Interest Rates, Negative Yields, and the Next Financial Crisis

“You could not live with your own failure. And where did that bring you? Back to me.”

-Thanos, Avengers: Endgame

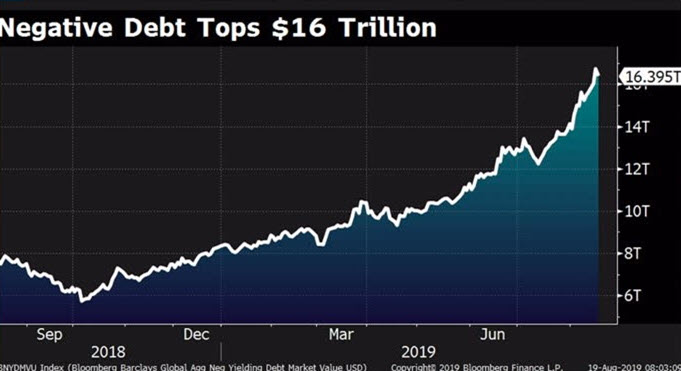

If you haven’t been stuck in a cave for the past year, you’ve probably seen quite a few articles about the nearly $20 trillion in negative-yielding bonds worldwide.

It’s hard to escape the news when you see charts like this:

Unfortunately, most news sources tend to explain these developments poorly, often conflating concepts and terminology.

For example, interest rates are different from the yields on bonds, which are also different from coupon rates on bonds.

Yet many journalists use “rates” and “yields” interchangeably and claim that everything is turning negative.

I’m going to lay out the insanity in this article, explain why the bond bubble is likely to end poorly, and – to end on a slightly positive note – describe how I’m staying out of it.

WARNING 1: This is more of an opinion-based article than the usual recruiting and career coverage on this site. It verges on conspiratorial. If you don’t like that, don’t read it.

WARNING 2: This article contains spoilers for Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame, in case you’re one of the ~10 people on Earth who has not seen these movies.

Negative Interest Rates and Negative Yields: Central Banks Gone Wild

This article is based on the latest YouTube tutorial in our channel, which you can get below:

Let’s start with the basics: “Interest rates” refer to the percentages that commercial banks charge to lend to one another in the short term.

In a normal economic and financial environment, these rates tend to be low-single-digit positive percentages (e.g., between 2% and 5%).

As I write this, these rates are negative in both the Euro area and Japan, while they’re still slightly positive in the U.S.

Some people have argued that these negative interest rates are “inevitable” or the result of a “savings glut.”

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Central banks set the target rate and further influence it through “open-market operations,” such as buying government bonds.

It’s true that the effective rate may differ from the targeted rate, and it’s also true that economic factors, demographics, fiscal policy, and savings rates affect these numbers.

But anyone who claims that central banks do not make a huge impact on overall interest rates is delusional.

If the ECB or Fed wanted to, they could raise target rates to 5% tomorrow.

They’re not doing that because they believe that the economy “needs” negative interest rates to avoid a recession, or that negative rates have already improved things.

NOTE: I’m not making this up – take a look at these comments from the incoming ECB head.

The flaw in this logic is that negative rates create just as many problems as they “solve.”

By keeping them extremely low or negative, central banks misprice risk, which leads to asset bubbles, unproductive investments, and risky, yield-chasing behavior.

Negative interest rates benefit the asset-owning wealthy elite, worsen wealth and income inequality, and do nothing for the average, middle-income person.

They make a disastrous impact on commercial banks, pension funds, and anyone with an inkling of common sense.

Negative yields are almost as silly as negative rates, but in some cases, there is a logical explanation for them – even if that explanation is “A massive bond bubble is forming.”

What Does a Negative Yield on a Bond Mean?

First, we need to define the terms that mainstream news sources often confuse.

As discussed above, “interest rates” usually refer to the rates that banks charge to lend to each other, such as the Fed Funds Rate in the U.S.

The coupon rate is the (typically fixed) rate that a corporate or government bond pays, such as 3% or 5% per year.

If a government issues a bond for a face value of $1,000 and a 3% fixed coupon rate, it pays $30 in interest on that bond each year until maturity.

Even if the bond’s market price rises to $1,200 or falls to $800, the government keeps paying $30 in interest each year because the 3% coupon rate applies to the face value of the bond.

A bond’s yield can refer to different concepts: the Yield to Maturity (YTM), the Yield to Worst (YTW), the Yield to Call (YTC), and more.

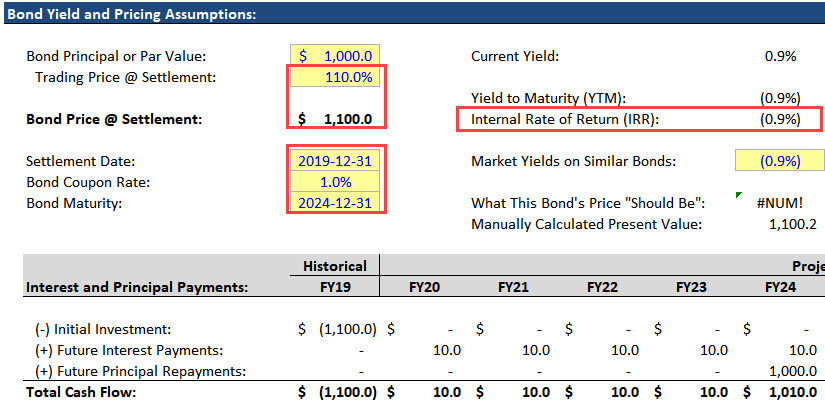

In this article, we’ll assume that “yield” means the Yield to Maturity (YTM), or the internal rate of return (IRR) of a bond if it is held to maturity.

The YTM is different from the coupon rate because it also depends on the bond’s current market price and its redemption value (how much you earn back at the end upon maturity).

Credit quality and prevailing yields on similar bonds in the market affect the YTM.

If similar companies start issuing bonds at higher yields, a company’s existing bonds will become less attractive, pushing down their market price.

That lower market price then increases the yield of the company’s existing bonds, pushing it closer to current market yields.

So, the following scenarios are all possible:

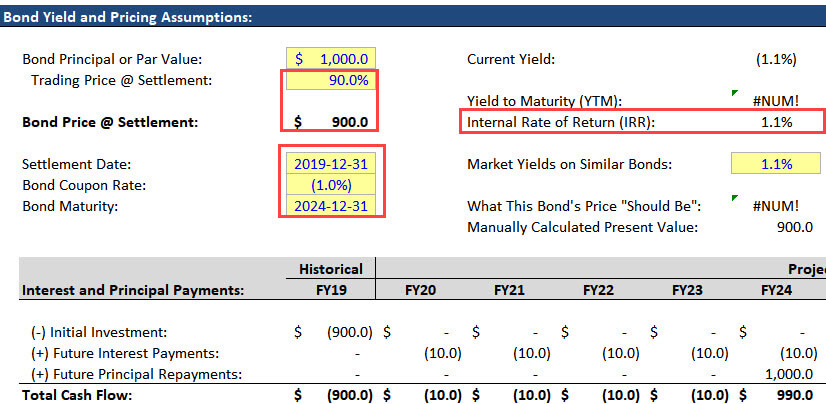

Negative Coupon Rate and Positive Yield

Yes, bonds with negative coupon rates are now a thing.

Just go to Denmark and ask any bank there!

As an investor, you get to pay someone else for the privilege of lending them money.

But hey, if the bond’s price falls low enough, a negative-coupon-rate bond could still produce a positive yield:

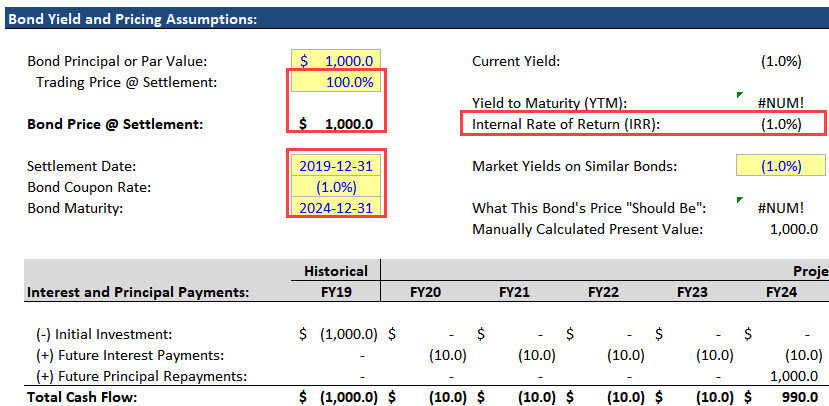

Negative Coupon Rate and Negative Yield

In this case, the market price can remain the same as face value or par value and a simple negative coupon rate will make the yield negative:

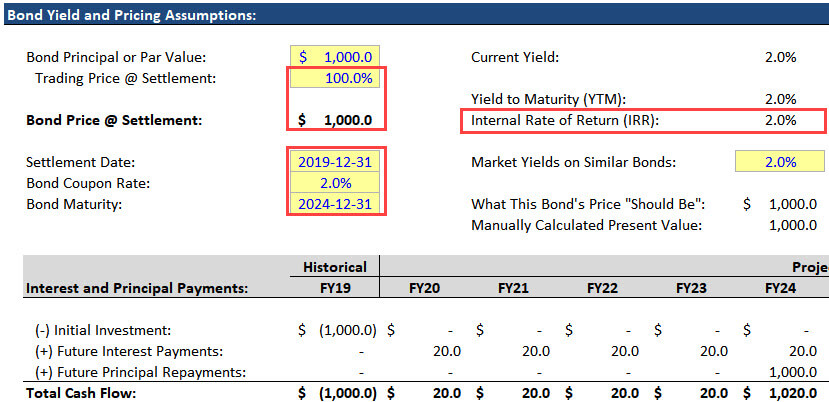

Positive Coupon Rate and Positive Yield

This is how bond investing “should” work: you earn modest interest income during the holding period and then earn back your principal upon maturity.

What a quaint concept!

Positive Coupon Rate and Negative Yield

In this scenario, you still earn positive interest income from bonds, but the market prices of those bonds get bid up, making the yields negative:

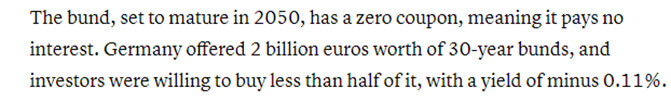

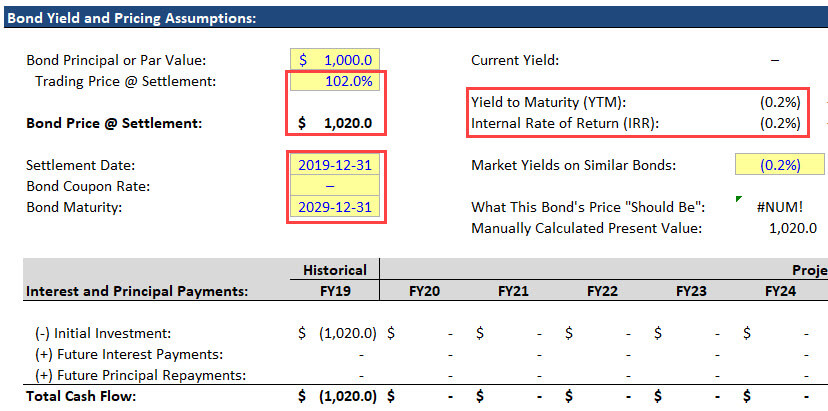

In real life, most bonds with negative yields are zero-coupon bonds issued by countries like Germany and Switzerland:

Investors bid up the prices of these bonds as soon as they’re issued.

So, if the bond’s face value is 1,000, maybe its market price increases to 1,020 right away.

With a 10-year maturity, a 0% coupon rate, and a redemption value of 1,000, the YTM of this bond is (0.2%):

Why Would You Buy a Negative-Yielding Bond?

Although interest rates, coupon rates, and yields are different concepts, they are connected.

For example, if overall interest rates in the economy are lower, then coupon rates will tend to be lower because they’re often based on an interest-rate spread.

And lower interest rates and lower coupon rates often mean that yields will be lower simply because bonds produce less interest income.

As yields fall, prices rise, and as prices rise, yields fall.

So, investors might buy a negative-yielding bond if they believe that overall interest rates, and therefore “market yields,” will fall even more in the future – so they can sell the bond at a higher price.

Also, many pension funds and insurance firms allocate certain percentages to “safe” government bonds for regulatory reasons.

If you’re required to buy negative-yielding government bonds to continue operating, you have to do it.

Some investors might also buy negative-yielding bonds as a currency play, especially if their funds are in USD, but they’re looking at opportunities worldwide.

With appropriate currency hedging, a negative yield can turn into a positive one, such as when U.S.-based investors buy European bonds and use USD/EUR hedges (see this article for more).

But the first explanation above is the simplest and most common one: investors buy negative-yielding bonds because they believe the bonds’ prices will keep increasing.

If you think about this for 5 seconds, you realize how insane it is.

Traditional bond investing is supposed to be about earning interest income, with some possibility of modest capital appreciation.

But negative interest rates and negative yields have turned bond investing into a casino where buyers keep waiting for the “greater fool” to come along.

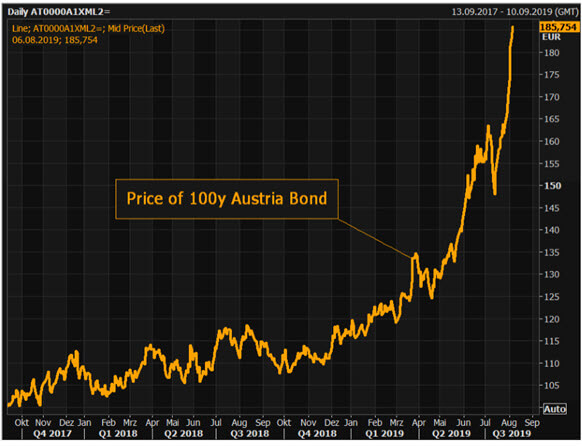

For a good example of this casino mentality, take a look at the price of the 100-year Austrian government bonds issued in 2017:

Because of the long maturity of these bonds, their duration and convexity are very high, making them extremely sensitive to small changes in market yields.

These bonds are up 70% year-to-date in 2019, and they trade at over 200% of par value.

Does that sound right?

Why Negative Interest Rates Won’t Work

This idea that negative rates will “stimulate growth” is a ridiculous one because Japan has been experimenting with quantitative easing and super-low-to-negative rates for 20+ years, and none of it worked.

There’s even an Investopedia article on the diminishing effects of QE in Japan.

The real reason for the low rates is that governments and corporations have racked up so much debt following the 2008 crisis that it would be impossible to service the debt with “honest rates.”

If interest rates were in the 4-5% range, there would be a wave of defaults everywhere.

Another reason for the low rates is that governments worldwide are attempting to devalue their currencies to boost their exports.

But once again, it’s not that simple in a complex system like the economy.

Yes, maybe negative interest rates prevent defaults or boost exports…

…but they don’t encourage personal consumption – they encourage people to shift their money around to different accounts:

Negative interest rates also encourage commercial banks to act irresponsibly by “investing” in riskier assets to chase yield and earn higher net interest income.

As soon as there’s a downturn, these banks will face a regulatory capital crisis as they record massive write-downs.

Finally, negative interest rates also allow ridiculous companies that lack real business models to survive indefinitely:

For more on this one, see our Uber valuation.

But who cares about rational decisions when SoftBank throws billions of dollars at any startup with a pulse? (bonus points if it has rainbow unicorns)

What’s the Endgame?

My prediction is that there will be an equivalent of “the snap,” but instead of half the life in the universe disappearing, bond prices will plummet.

Buying negative-yielding bonds only makes sense if you plan to sell them long before maturity – but what if the greater fools disappear?

Almost anything could cause that, including:

- A sovereign debt crisis.

- Higher inflation.

- Economic recovery or a return to growth.

- A currency crisis.

We’re in uncharted territory, but it seems likely that something will blow up the bond market.

How I’m Staying on the Sidelines

NOTE: This is not investment/legal/tax/business advice but simply for informational purposes, do your own research, etc.

My asset allocation has changed since the last time I reported on it at the start of 2019, but to streamline this part, I’ll focus on just one brokerage account.

I changed the allocation there to the following split earlier this year:

- U.S. Total Stock Market Fund: 20%

- U.S. Small-Cap Value Fund: 20%

- Long-Term U.S. Treasuries: 20%

- Short-Term U.S. Treasuries: 20%

- Gold: 20%

This is a variation on Ray Dalio’s “All Weather” portfolio, and it has generated average annualized returns of 6-7% historically with a maximum annual loss of ~11%.

If I had a stable corporate job that I planned to stay in for the next 30 years, I would contribute a percentage of my income each month and use a 90% Equities allocation.

But that’s not my situation: I earned a lot in my 20s and 30s, and I will probably earn far less in the future.

So, I have to be more conservative and focus on capital preservation more than high annualized returns.

I have some U.S.-based municipal bonds in other accounts, but I’m staying very far away from all corporate bonds and all non-U.S.-government bonds.

And if U.S. Treasury yields turned negative, I would sell my holdings and move to cash.

Will Ironman, The Hulk, and Time Travel Save Us?

After the Avengers failed to defeat Thanos in Infinity War, they returned and beat him at the start of Endgame, with an assist from Captain Marvel.

But it didn’t work as intended because Thanos had already destroyed the Infinity Stones to prevent others from using them again.

They couldn’t reverse “the snap,” so they were stuck with half the universe missing.

This is similar to what central banks are doing now with negative interest rates: completing the same action repeatedly, even though they know it won’t work.

The Avengers eventually reversed the snap because they had Tony Stark, Bruce Banner, a newly invented time-travel machine, and the ability to create new timelines.

But we do not have Tony Stark, Bruce Banner, or time travel.

We have… gold… and Bitcoin?

So, maybe you should prepare yourself for the snap.

Thanos might win for good this time.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews

Comments

Read below or Add a comment

Hi Brian, great article.

I’m about to enter IB in NYC at a BB. As you know, pretty much EVERYONE is jumping on the PE bandwagon and trying to jump to MFs/Upper MMS in search of higher pay, less hours/grunt work etc.

But most of these programs force you out after two years, and unless you get into HSW, it’s unlikely you end up back at these firms.

I’m a pretty poor test taker, and doubt I could score high enough on the GMAT get into HSW business schools. Assuming I can’t break 700 (or even 650), and wouldn’t end up getting into these top business schools, would you recommend I just stay in banking (assuming I enjoy the work)?

I’m not dead-set on PE as my long term career, and also understand it is nearly impossible to make partner level at these firms since no one is leaving. I’m still open to other investing roles that don’t require an MBA and also pay as much as banking (private credit, real estate??)

Thanks for your help!

I think you’re making too many assumptions about future events, and you’re not factoring in different possible outcomes. For example, yes, you probably won’t be promoted directly at the mega-funds, but you could go from there to middle-market funds, growth equity, hedge funds, etc., so you don’t “need” a top business school to advance unless your only goal in life is to become a Partner at KKR or Blackstone.

Also, you have no idea whether or not you can get into the top business schools because it depends on events over the next few years and, unlike law school, is about more than just your test score.

So… I think you are being overly paranoid. You should start the IB role, and if you’re not certain you want to go into PE, just interview around for other roles, like PE at smaller funds, private credit, real estate, growth equity, etc., and see what sticks.

Any comments on emerging market bonds? Heard their yields are better.

I haven’t looked at them in detail lately, so can’t really say. But I think it’s probably a “pick your poison” scenario – yes, yields are higher, but so is default risk. So… do you lose money holding a bond to maturity, or do you lose it when the government or company defaults? This is why I’m staying away from anything bond-related outside the U.S.