The Equity Method of Accounting: The Full Guide

When it comes to confusing accounting topics, partial stakes in other companies and the equity method of accounting consistently rank near the top of the list.

The equity method is used when one company has “significant influence,” but not control, over another company.

In practice, that means “an ownership stake between 20% and 50% in another company,” though some companies also use it for stakes below 20%.

When the stake is greater than or equal to 50% but less than 100%, consolidation accounting, which creates a Noncontrolling Interest, is used.

That’s a separate and more complicated topic, so we’re going to focus on just the equity method here.

You’ll also see the names “equity investments” and “associate companies” used to refer to these partial stakes.

They all relate to the same concept; the “equity method of accounting” is the process, and the “equity investments” or “associate companies” are the line items created on the Balance Sheet.

You can see many examples of this accounting method in real life if you look through press releases and financial statements:

Why Does This Matter? Is the Equity Method a Common Interview Topic?

The equity method of accounting is not a “common” interview topic.

However, it can come up, especially if you’re in an industry or region where joint ventures and partnerships are common, or if you have more work experience.

Possible interview questions include:

- What is the equity method? When do you use it?

- Explain the flow of Net Income and Dividends when a Parent Company owns 20% or 30% of a Subsidiary Company.

- How do Equity Investments or Associate Companies factor into Enterprise Value vs. Equity Value? What about valuation/DCF analysis?

That said, the equity method of accounting is still more of an on-the-job issue.

You need to know about it because you’ll work with companies that list Equity Investments, Associate Companies, and Joint Ventures on their Balance Sheets.

The Video Tutorial and Sample Excel File

To get this article in video format, take a look at the YouTube example from our channel and the Excel example below:

- The Equity Method of Accounting and Equity Investments (XL)

- The Equity Method of Accounting and Equity Investments – Slides (PDF)

We also cover this topic in more depth in our Advanced Financial Modeling course (see the “More Advanced Accounting” module):

Advanced Financial Modeling

Learn more complex "on the job" investment banking models and complete private equity, hedge fund, and credit case studies to win buy-side job offers.

learn moreThe Bare Minimum You Must Know About the Equity Method of Accounting

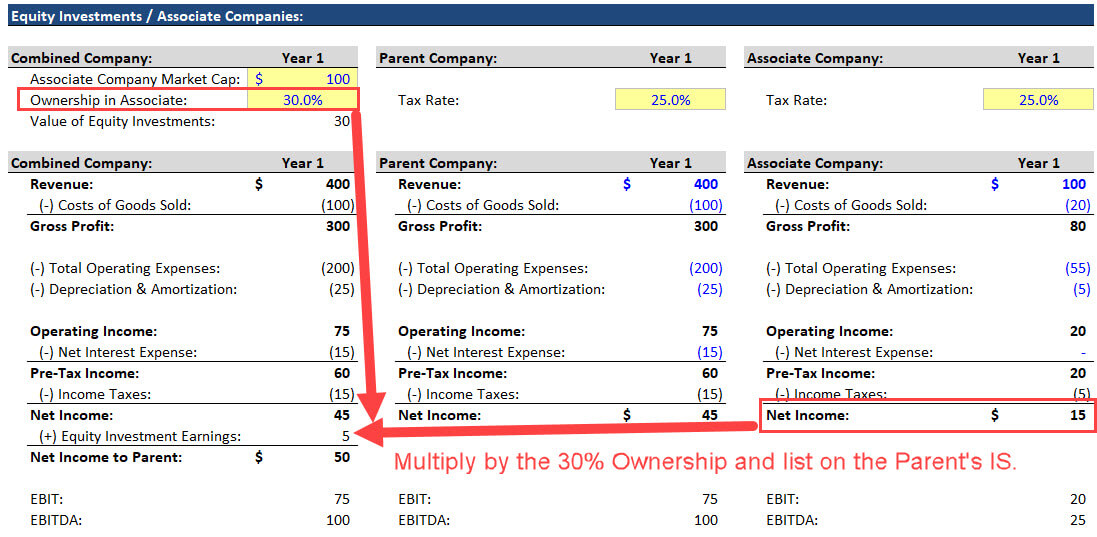

The main idea is that Parent Co. records its Ownership Percentage * Sub Co.’s Net Income on its Income Statement under “Equity Investment Earnings,” or a similar name.

But it records nothing else from Sub Co., so the financial statements are not consolidated.

Here’s a simple example of the Income Statement for a Parent Company with a 30% stake in a Sub Co.:

(Click to view larger version.)

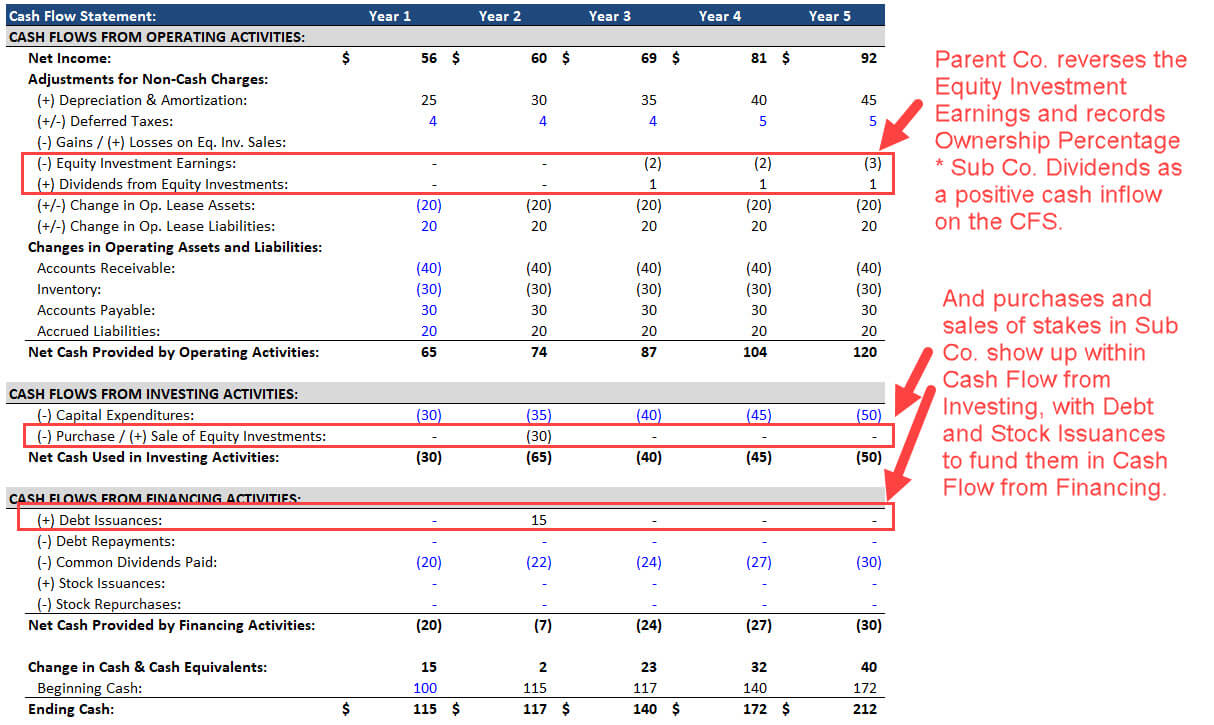

Then, Parent Co. reverses this “Equity Investment Earnings” line item on its Cash Flow Statement and records its Ownership Percentage * Sub Co.’s Dividends as a positive on its CFS.

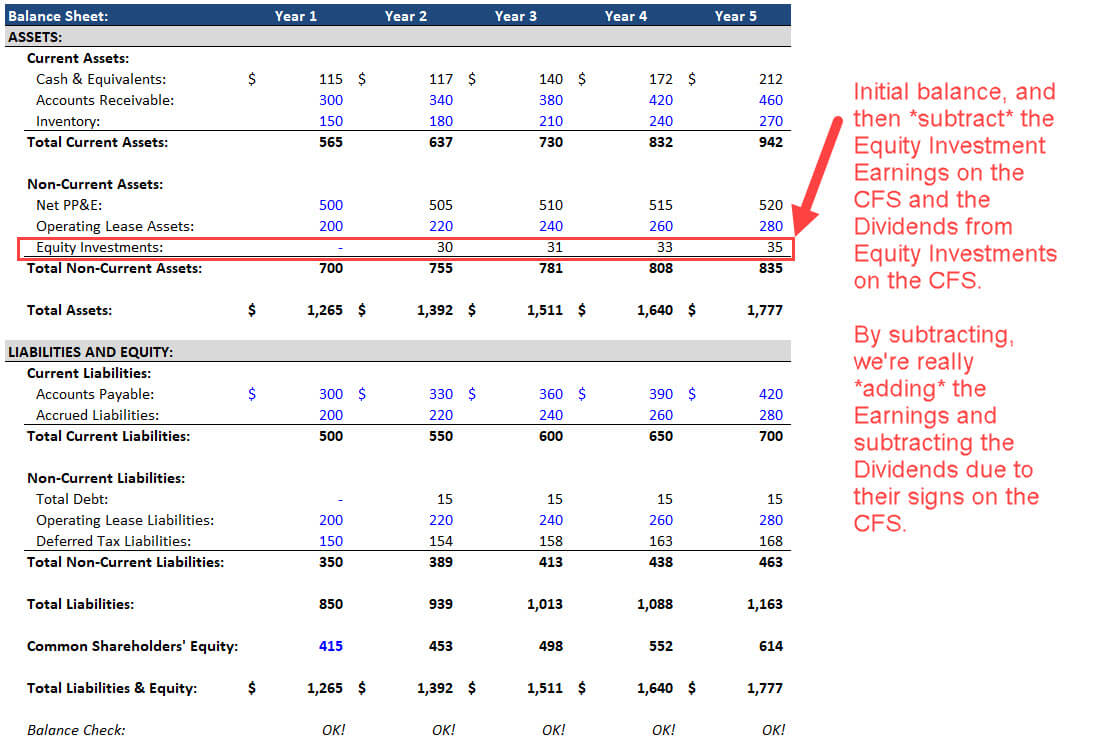

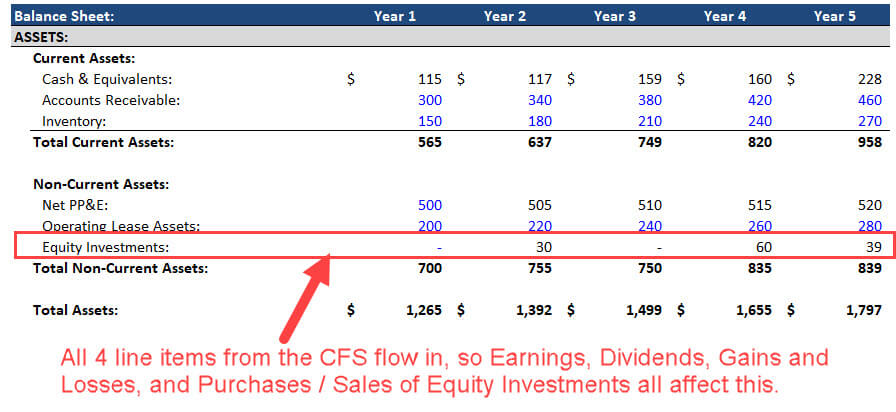

On the Balance Sheet, the “Equity Investments” line item on the Assets side represents the Parent’s minority stake in this Sub Co.

Both Cash Flow Statement line items link into Equity Investments: Equity Investment Earnings increases it, and the Ownership Percentage * Sub Co.’s Dividends reduces it.

You subtract this “Equity Investments” line item when calculating Enterprise Value because it counts as a non-core-business asset.

Also, as you can see from the screenshot above, metrics like EBIT and EBITDA completely exclude contributions from Equity Investments.

But Equity Value reflects the value of Net Assets to Common Shareholders, so it includes these Equity Investments.

Therefore, you must subtract Equity Investments so that the numerator, Enterprise Value, and the denominator of valuation multiples (EBIT or EBITDA) ignore Equity Investments.

If you want to go beyond that bare minimum, here’s the full set of steps in the equity method:

Equity Method of Accounting Example, Part 1: Purchasing a Minority Stake and Recording Net Income and Dividends from It

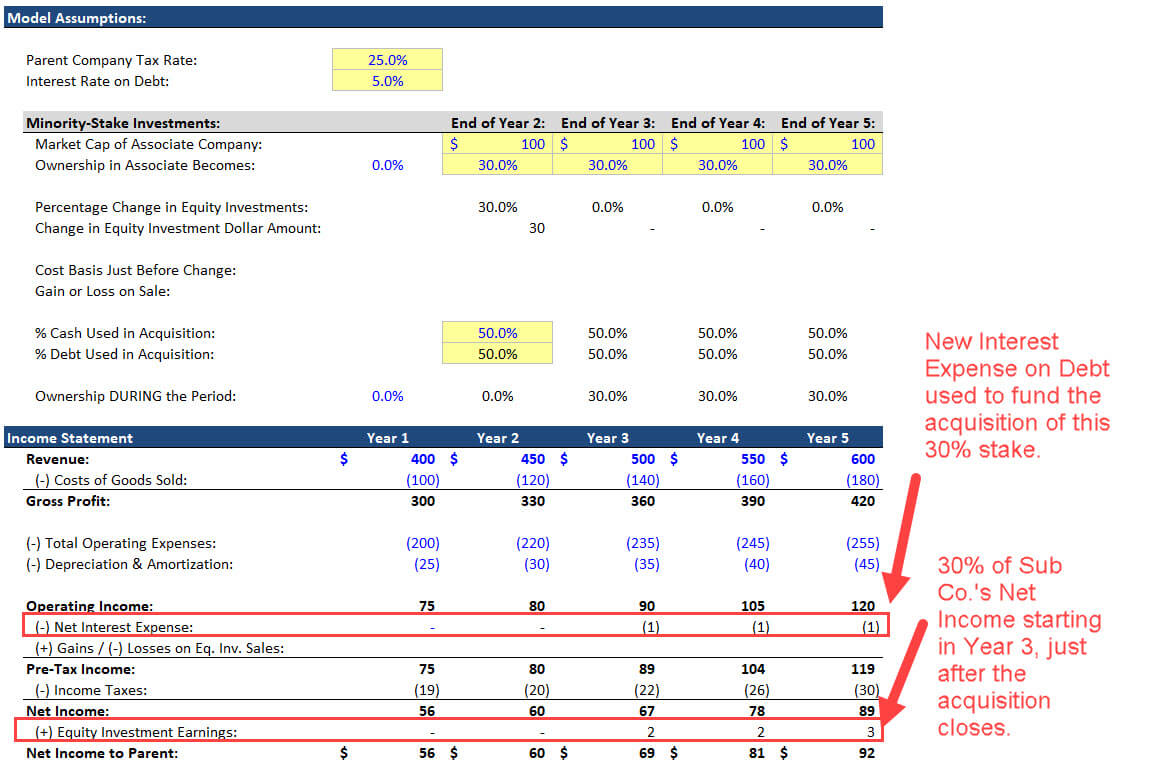

Let’s assume that Parent Co. has $400 million in revenue, growing to $600 million in Year 5.

It’s about 10x the size of Sub Co., which has $40 million in revenue, growing to $60 million in the same period.

In Year 1, Parent Co. owns no stake in Sub Co., and at the end of Year 2, it acquires a 30% stake in Sub Co., when Sub Co.’s Market Cap is $100 million.

It funds this purchase of the 30% stake with 50% Cash and 50% Debt.

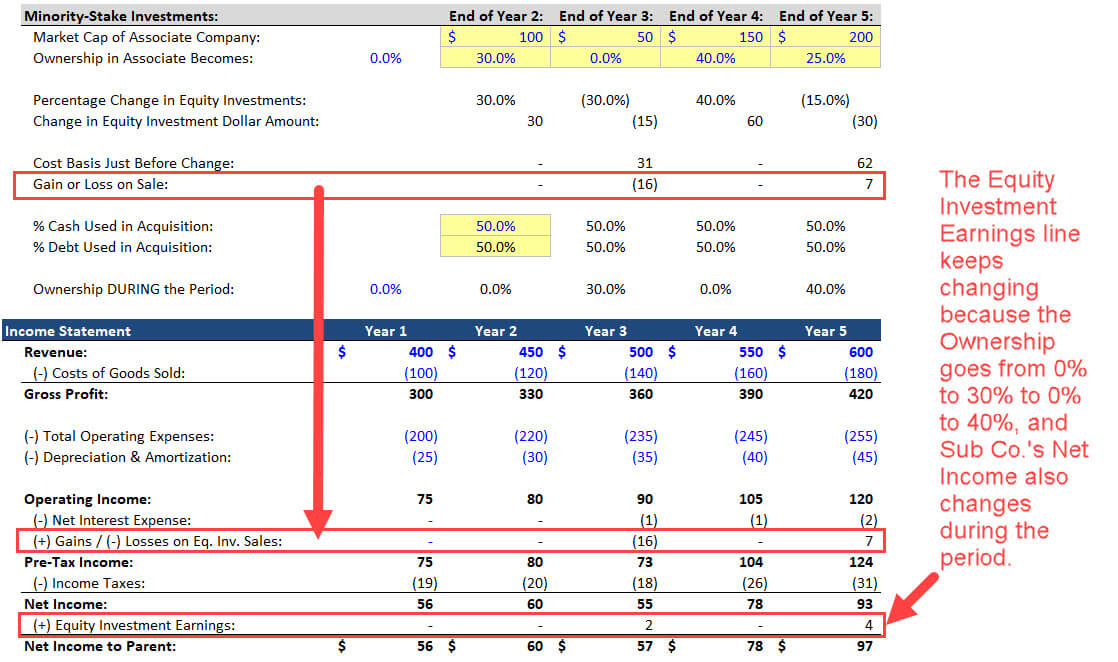

Here’s the Income Statement for Years 1 – 5:

(Click to view larger version.)

We assume here that Sub Co.’s Market Cap stays constant at $100 million throughout this period.

However, that assumption does not matter as long as the initial 30% stake also stays the same.

Unrealized Gains and Losses on Equity Investments do not appear directly on the Income Statement, so even if Sub Co.’s Market Cap increased to $1 billion or fell to $10 million, nothing would change.

Parent Co. would record a change only if it sold some of its stake in Sub Co., resulting in a Realized Gain or Loss.

The initial purchase of a 30% stake is quite simple to record on the Cash Flow Statement:

(Click to view larger version.)

On the Balance Sheet, the initial Purchase of Equity Investments at the end of Year 2 creates the “Equity Investments” line item on the Assets side.

It may also be called “Associate Companies,” “Associates,” or “Investments in Equity Affiliates.”

After it’s created, it increases by the Equity Investment Earnings and decreases by Dividends from Equity Investments:

(Click to view larger version.)

Since Parent Co. does not control Sub Co., it does not “get” Sub Co.’s Net Income in cash each year.

It owns less than 50% of the company, so it can’t walk over to Sub Co. and say, “Hey! Please give us all your Net Income right now. Forget about the other shareholders.”

Therefore, Earnings from Equity Investments are reversed on the Cash Flow Statement, which means they’re negative on the CFS in most cases.

Parent Co. receives in cash only Sub Co.’s Dividends * its Ownership Percentage.

In real life, it’s more complicated than Net Income and Dividends.

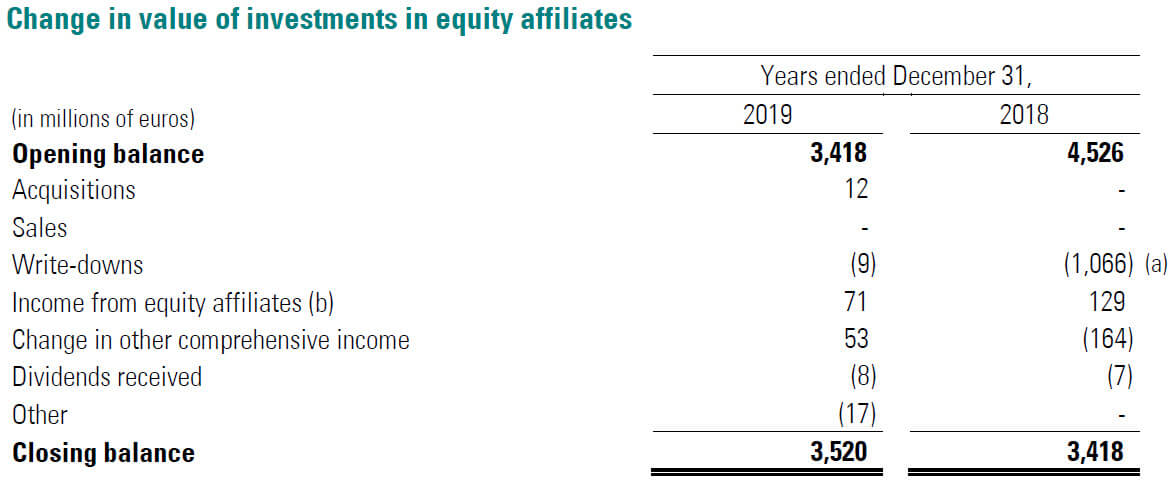

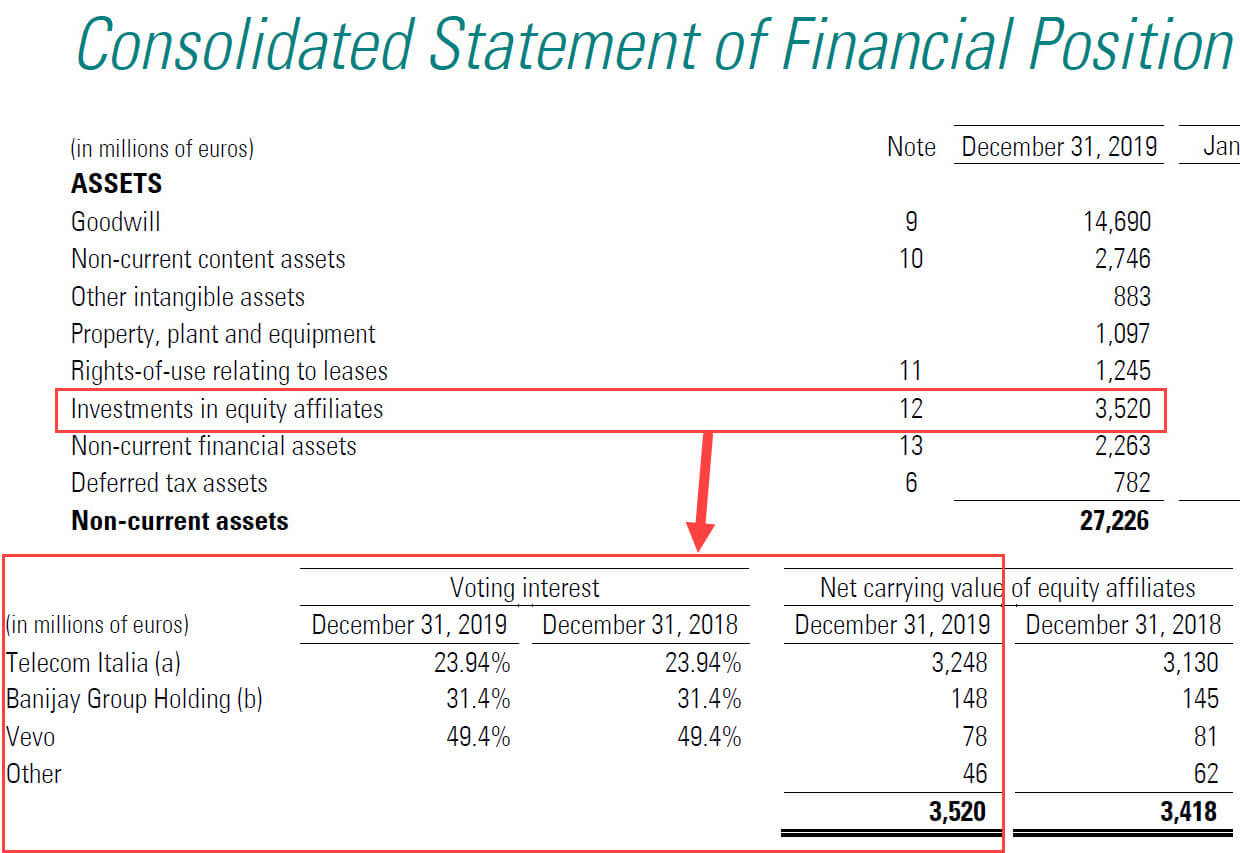

For example, here are the items that affect Vivendi’s Equity Investments:

(Click to view larger version.)

However, most of these additional items, such as the write-downs, are non-recurring, so they do not factor into most financial projections.

Equity Method of Accounting Example, Part 2: Increasing and Decreasing the Minority Stake

If Parent Co. changes its ownership in Sub Co., the accounting gets more complex.

Recording an increase in the stake is the simple part: show the acquisition within Cash Flow from Investing on the Cash Flow Statement and link it into Equity Investments.

For example, if Parent Co. increases its stake in Sub Co. to 40%, and Sub Co.’s Market Cap is still $100:

- Record (40% – 30%) * $100 = $10 as a negative $10 on the Cash Flow Statement.

- Make Equity Investments on the Balance Sheet increase by $10.

But if Parent Co. decreases its stake in Sub Co., there will almost always be a Realized Gain or Loss to record.

To make this example more “interesting,” we’ll assume that Sub Co.’s Market Cap decreases from $100 to $50, then increases to $150, and then increases again to $200.

During that time, Parent Co. goes from 30% ownership to 0% to 40% to 25%.

This example corresponds to the Excel file above, so you can see everything laid out there.

To calculate the Realized Gain or Loss in each period, we need the Cost Basis right before the change takes place, as well as the market value at which the stake was sold.

- Cost Basis = Equity Investments at Previous Year’s End + Equity Investment Earnings This Year – Dividends from Equity Investments This Year

This formula looks slightly different in the Excel file because of the signs of these items on the CFS, but it does the same thing.

Then, to calculate the Gain or Loss, we use this formula:

- Realized Gain or Loss = IF(Ownership Percentage Decreases, (Sub Co. Market Cap * Previous Ownership Percentage – Cost Basis) * –Percentage Change / Previous Ownership Percentage, 0)

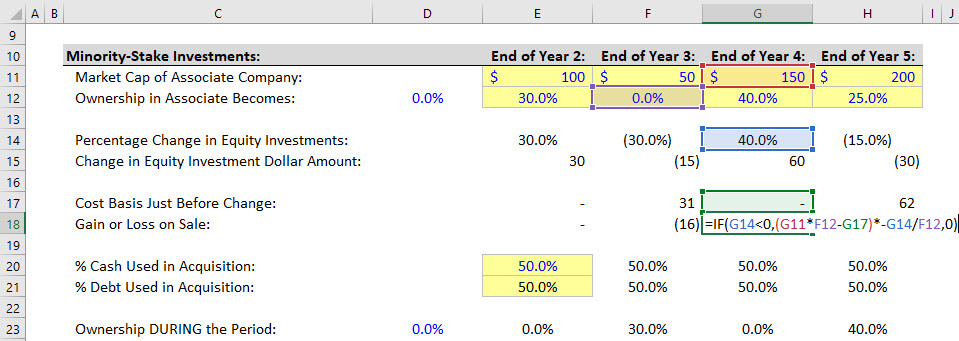

Here it is in Excel:

(Click to view larger version.)

The first part of this formula calculates the Gain or Loss on the full stake.

But Parent Co. does not necessarily sell the full stake – it might just sell 50% or 25% or 75% of its stake, so the Percentage Change / Previous Ownership Percentage adjusts for that.

The Percentage Change will be negative when the ownership decreases, so the negative sign in front flips it to a positive.

To link the statements, we record these Realized Gains and Losses on the Income Statement:

(Click to view larger version.)

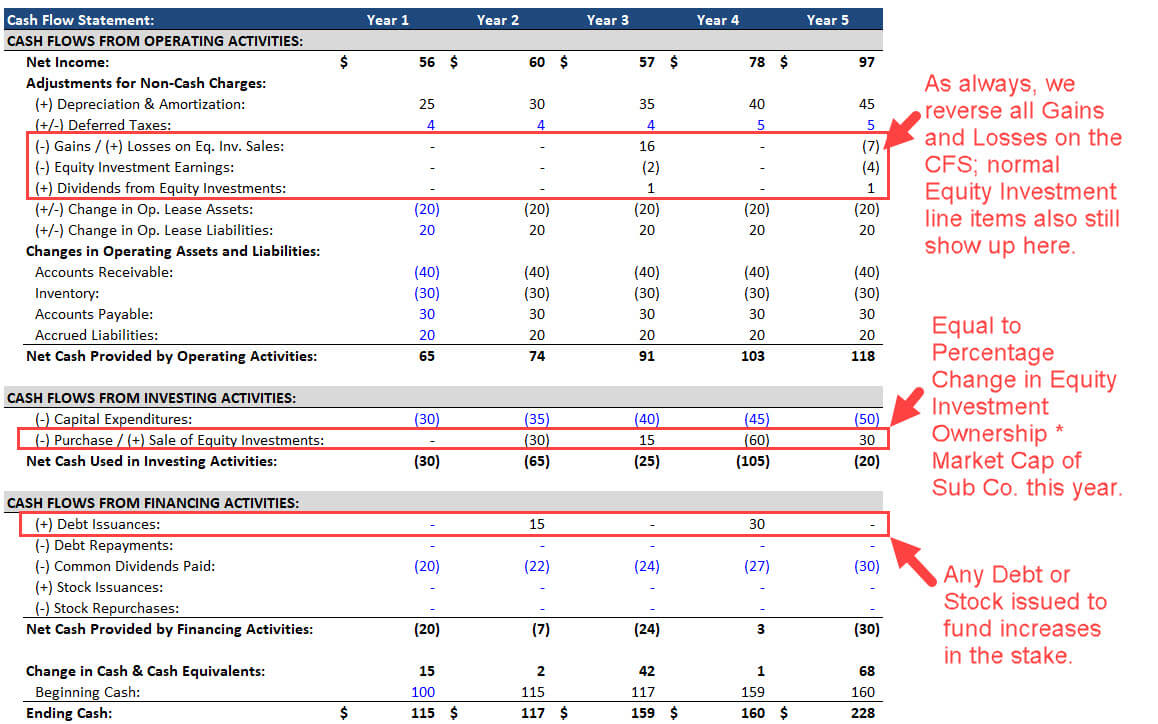

On the Cash Flow Statement, we:

- Reverse the Realized Gains or Losses in Cash Flow from Operations.

- Record the entire Change in Equity Investment Dollar Amount in Cash Flow from Investing.

- And record Debt or Stock issuances for additional purchases in Cash Flow from Financing.

If there’s a decrease in ownership, the Realized Gain or Loss + Change in Equity Investment Dollar Amount equal the change in Equity Investments:

(Click to view larger version.)

(Click to view larger version.)

This example is more complex than real-life scenarios because no companies change their ownership in other companies by this much each year.

In most cases, companies acquire these stakes, let them sit around, and then sell the stake or purchase more years into the future.

As long as you understand the flow of Net Income and Dividends, you should be in good shape.

And if you’re dealing with the sale of an Equity Investment, you can always look up the formulas in this article.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Equity Method of Accounting

Here are a few common/recent questions we’ve received about this topic:

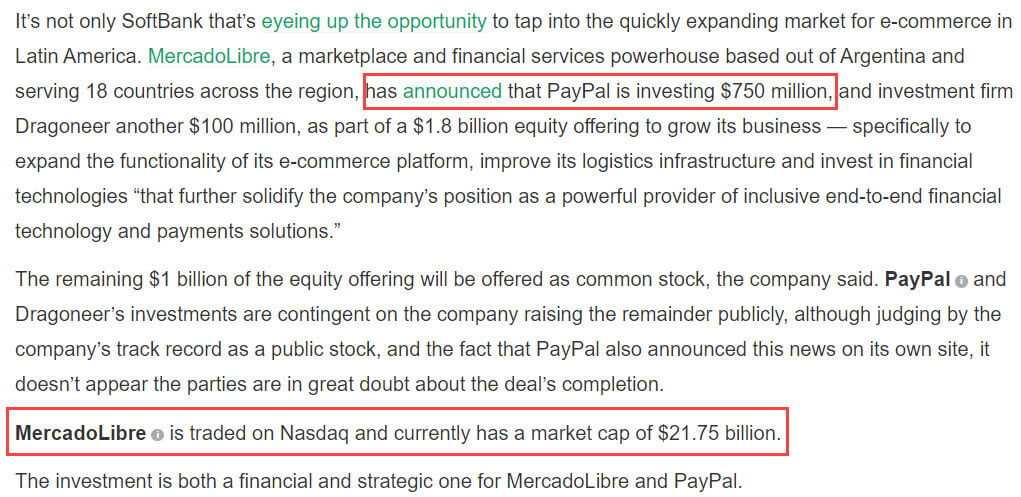

Q: In PayPal’s earnings, they outlined how their EPS increased by $0.58 due to Unrealized Gains from their Mercado Libre minority stake.

Why was this Unrealized Gain shown on the Income Statement if the Mercado Libre stake is an Equity Investment?

A: Because it’s not an Equity Investment!

PayPal spent ~$750 million to acquire a stake in Mercado Libre when the company was already worth around $22 billion:

This ~3% ownership percentage is much lower than the normal 20% required for the equity method of accounting.

So, the company is most likely classifying this investment as “Equity Securities,” which means that Realized and Unrealized Gains and Losses show up on the Income Statement.

Q: What about the Enterprise Value calculation?

Should I use the Market Value of the Equity Investments?

A: In theory, yes, but in practice, you may not be able to find it.

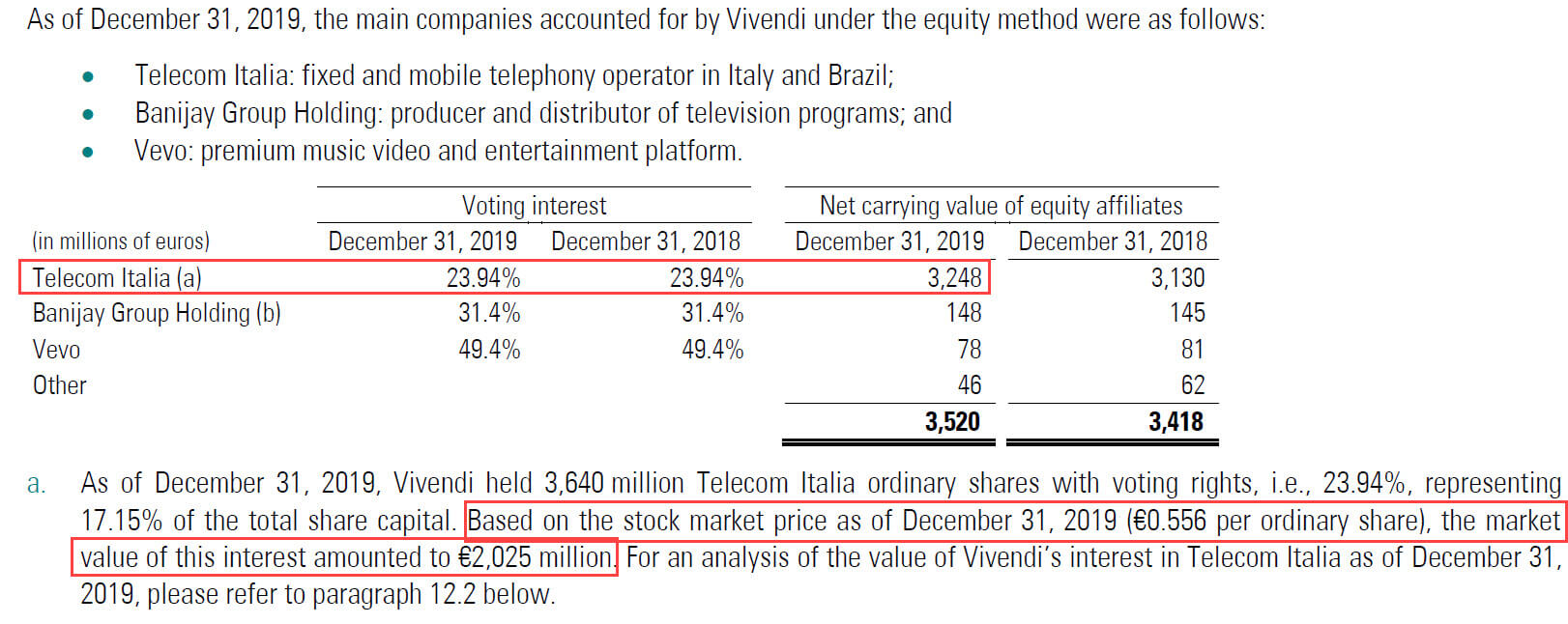

If the Equity Investments are significant (e.g., > 15% of the parent company’s Equity Value), or they represent large, public companies, this point matters.

But if they represent smaller, private companies with no listed market value, you won’t be able to do much.

Another issue is that sometimes companies disclose the market value of only certain Equity Investments, but not the entire balance:

Do what you can, but don’t kill yourself if you can’t find the market values.

Q: Wait a minute, why do Equity Investments decrease when the Sub Co. issues Dividends to the Parent Co.?

Shouldn’t that boost Parent Co.’s Assets?

A: The Dividends from Sub Co. do increase Parent Co.’s Cash balance – just not its Total Assets.

Parent Co.’s Cash balance increases, and its Equity Investments decrease, so the changes cancel each other out, and Total Assets stay the same.

The Equity Investments line acts as a “mini-Shareholders’ Equity” for the minority stake.

Just like normal Shareholders’ Equity, it increases when Net Income flows in and decreases when Dividends are paid.

The difference is that it’s only for this minority stake and doesn’t represent all the shareholders in the other company.

Q: What about when an investment firm acquires a minority stake in a company? Does this accounting method apply?

A: If the firm classifies the minority stake as an Equity Investment, then yes, the same method applies to the investment firm’s financial statements.

However, you never deal with those statements if you’re analyzing normal companies.

And this type of deal doesn’t change anything about the normal company’s financial statements.

For more on this one, see our growth equity tutorial and case study.

The Equity Method of Accounting: Final Thoughts

Some of these changes are tricky, but as long as you understand the basics about Net Income, Dividends, and Enterprise Value, you should be fine.

As with similar technical articles/tutorials, I am closing the comments on this one because this site offers career advice, descriptions of different industries and jobs, and only the occasional technical tutorial.

If you have in-depth questions on this topic, feel free to ask them within our courses.

And if you have shorter/simpler questions, feel free to ask them in a relevant video on the YouTube channel.

—

If you liked this article, you might be interested in reading Enterprise Value vs Equity Value: The Complete Guide.

Free Exclusive Report: 57-page guide with the action plan you need to break into investment banking - how to tell your story, network, craft a winning resume, and dominate your interviews